Acta Paedagogica Vilnensia ISSN 1392-5016 eISSN 1648-665X

2022, vol. 48, pp. 87–100 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/ActPaed.2022.48.5

School Leaders’ Attitudes, Expectations, and Beliefs Starting a Character Education Training in Latvia

Manuel Joaquín Fernández González

University of Latvia, Faculty of Education, Psychology and Art,

Scientific Institute of Pedagogy

manuels.fernandezs@lu.lv

Svetlana Surikova

University of Latvia, Faculty of Education,

Psychology and Art, Scientific Institute of Pedagogy

svetlana.surikova@lu.lv

Abstract. This article explores school leaders’ expectations and beliefs when starting a professional development course about character education in Latvia. The survey used mixed methods, involved 30 participants, and was conducted in 2020. School leaders expected to enhance their practical know-how in this field, the desired opportunities for personal reflection and sharing with colleagues, and believed that shared values and a friendly atmosphere were the key points. The findings can be useful for future similar initiatives.

Keywords: character education, professional development, school leader, training programme.

Mokyklų vadovų nuostatos, lūkesčiai ir įsitikinimai pradedant charakterio ugdymo mokymus Latvijoje

Santrauka. Straipsnyje nagrinėjami Latvijos mokyklų vadovų lūkesčiai ir įsitikinimai pradedant profesinio tobulėjimo kursą apie charakterio ugdymą (toliau – programa). Atliktame tyrime nagrinėti šie klausimai: kokios buvo mokyklų vadovų nuostatos ir lūkesčiai pradedant programą? Kokie buvo jų pirminiai įsitikinimai apie savo žinias ir lyderystės kompetenciją šioje srityje? Kokių jie turėjo pirminių įsitikinimų apie savo vaidmenį ir įtaką mokinių moraliniam brendimui ir jų pačių moraliniam tobulėjimui?

Norint atsakyti į šiuos klausimus, 2020 m. pavasarį ir rudenį atlikta apklausa naudojant anketą su uždarais ir atvirais klausimais. Apklausoje dalyvavo 30 Latvijos mokyklų vadovų (iš Rygos, Rygos apylinkių ir Siguldos). Mokyklų vadovų profesinės patirties įvairovė suteikė tyrimui reikšmingų įžvalgų.

Dalyviai pasitikėjo savo profesine patirtimi ir kompetencija, tačiau kartu buvo pasirengę tobulinti profesinę praktiką ir žinias savo srityje. Jie pabrėžė norą dalytis žiniomis ir idėjomis bei išreiškė viltį, kad turės galimybę refleksijai ir bendrautii. Tyrimo dalyviai pabrėžė, kaip svarbu sukurti draugišką, bendra vertybių ir dorybių sistema besiremiančią atmosferą. Vienas iš tvirčiausių jų įsitikinimų buvo tas, kad jie patys turi įkūnyti dorybes, kurias norėtų matyti savo mokiniuose, ir užmegzti pasitikėjimu grįstą bendravimą kaip mokinių ir jų pačių moralinio augimo sąlygą.

Tyrimo rezultatai buvo naudinga atspirtis apibrėžiant tolesnio programoje vykdomo veiklos tyrimo kontekstą: jie naudojami kaip orientyras vertinant dalyvių nuostatas apie programos įgyvendinamumą ir įtaką jai pasibaigus. Šie radiniai taip pat gali būti vertingi panašioms iniciatyvoms ateityje, nes atskleidžia svarbių aspektų, į kuriuos reikia atsižvelgti organizuojant charakterio ugdymo lyderystės mokymo kursus.

Pagrindiniai žodžiai: charakterio ugdymas, profesinis tobulėjimas, mokyklos vadovas, mokymo programa.

___________

Received: 15/09/2021. Accepted: 15/02/2022

Copyright © Manuel Joaquín Fernández González

Introduction

Character (i.e., moral, virtue) education is a challenging endeavour in which families and schools should collaborate. School leaders play a pivotal role in achieving a holistic approach to the education process (Tzianakopoulou & Manesis, 2018), embedding an integrated whole-school approach to character education (Walker et al., 2017). But for carrying out this task effectively, they need evidence-based professional development. According to Character.org (2016), one of the key indicators of exemplary implementation of character education at school is that all school staff, including leading staff members, “receive ongoing staff development” about character education (p. 16).

In Latvia, after the falling of Soviet Union, the political apparatus that controlled school principals disappeared. This fact increased school principals’ formal authority and practical power at school, as they had more freedom of decision. After 30 years, and in spite of some recent reforms regarding school principals (Cabinet of Ministers, 2015, 2016a), this situation can still be felt. For example, the State Education Quality Service (SEQS) of the Republic of Latvia recently stated that, for ensuring the quality of the educational institutions, “the school principal plays a central role, because s/he is the one who takes the decisions, and has to take the responsibility about his/her contribution for the development of each pupil and of the institution” (SEQS, 2016, p. 15). Recently, character and virtue education at schools have been under intensive discussions in Latvia, leading in 2016 to the adoption of the Cabinet of Ministers’ regulation No 480 “Guidelines for the upbringing of learners and the procedure for evaluating information, teaching aids, materials and teaching/learning and upbringing methods” (Cabinet of Ministers, 2016b). The guidelines include twelve virtues to be developed by pupils at school as the manifestation of their personal free thinking and behaviour, namely: responsibility, studiousness, courage, honesty, wisdom, kindness, compassion, moderation, self-control, solidarity, justice, and tolerance. Those virtues are intended to facilitate the practice of a number of values considered to be of particular importance: life, respect, freedom, family, marriage, work, nature, culture, the Latvian language, and the Latvian State. In this regulation (Cabinet of Ministers, 2016b), it is stipulated that the school principal is responsible for the implementation of those rules (No. 2), and that the decisions of the School council in this regard have only a recommendatory character (No. 24). The guidelines of the current educational content reform project School 2030 (Skola 2030, 2017) integrate these objectives and use the language of virtues and values.

Many scholars have reported on the importance of school principals’ ethical stance and ethical leadership (Boydak Özan et al., 2017; Chan et al., 2019), of their character and their personal example, showing virtues in action (Chan et al., 2019; The National Society, 2017; Walker et al., 2017), of their professional identity (Crow et al., 2017), and of their spiritual and ethical values (Elmeski, 2015). Several recent studies addressed the role of the school principal in character education (Arthur et al., 2017; Francom, 2016; Wahyono et al., 2018). The Character.org framework for character education (2016) suggests that the school character education initiative should have “leaders, including the school principal, who champion character education efforts, share leadership, and provide long-range support” (p. 18). There is a number of studies about the characteristics and effective practices of character education leaders (Francom, 2013; Navarro et al., 2016; Murray et al., 2019; Walker et al., 2017). For instance, Walker et al. (2017) reported that successful character education leaders highlight the centrality of character education “to the culture, values and vision of the school,” take “a whole-school approach,” and exemplify positive character traits in interactions with others (p. 5). Authentic leaders lead by the example, which produces a kind of “emotional contagion” in the school culture (Avolio & Gardner, 2005, p. 326). School principals need also specific knowledge of the field, they “need to understand character, character development and character education, be instructional leaders for it, model good character, and empower all stakeholders in the school” (Berkowitz, 2011; Berkowitz et al., 2017, p. 42). They need to improve their own leadership (Elmeski, 2015) to effectively manage diversity (Romanowski et al., 2019) and promote developing leadership capacity in others (Huggins et al., 2017). The scientific literature also often refers to the relational dimension of leadership for character education. According to Walker et al. (2017), one of the key features of effective leadership of character education is to “maintain focus, momentum and ongoing communication” (p. 41); and for Bass and Steidlmeyer (1999), “a person becomes virtuous within a community” and “for the community” (p. 196). According to a six-country study (Chan et al., 2019) based on an analysis of school principals’ self-perceptions regarding their character, professional knowledge and skills, administrative style and duties, staff and students’ affairs management, it was concluded that “principals of many countries are in great need for professional development’ and they believe ‘in professional ethics in school leadership” (pp. 53–54).

Effective school-family collaboration and parental involvement are crucial elements of a successful educational environment (Deslandes, 2019; Johnson et al., 2004; Larocque at al., 2011; Peña, 2000; Raborife & Phasha, 2010), and they are especially important for successful implementation of character education (Agboola & Tsai, 2012; Berkowitz & Bier, 2006; Berkowitz et al., 2008, 2017). A recent research report (Fernández González, 2019) based on a survey involving more than 2250 respondents (pupils and parents, pre-service and in-service teachers, school leaders and educational authorities) from various Latvian schools showed a great diversity of understanding of what character (moral, virtue) education means. According to 127 Latvian school leaders and 32 educational authorities who participated in the abovementioned study, schools have to develop pupils’ characters and encourage good values (86% agreed), facilitating pupils’ moral growth is part of the teacher’s role (75% agreed), but teachers are not sufficiently or absolutely not prepared for this work (42% agreed) (Fernández González, 2019, 2020). Regarding the promotion of character education at school, school leaders and educational authorities emphasized that there is a large need for collaboration with families and implementing more practical rather than just theoretical activities.

Regarding Latvian school leaders’ training needs for implementing character education, school leading staff and educational authorities underlined the need to support school leaders in the implementation of character education at schools in the following ways: 1) offering them practical educational opportunities based on real situations, in particular regarding the development of a school culture supportive of character education; 2) addressing the skills of communicating with parents about pupils’ character growth in the school leaders’ career development plan; 3) facilitating school leaders’ self-knowledge and personality development (Fernández González, 2019, 2020). These identified needs are partly in line with the findings of the exploratory qualitative study presented by Hourani and Stringer (2015), who argue that school principals’ “individual professional needs should have been addressed within the scope of professional development and through an individualised career development plan” (p. 337), and that their professional development should be effective, applicable to practice and offering opportunities “to see school-based and hands-on examples” (p. 333). The effective professional development for school leaders is extremally important in the midst of educational reforms in different countries (Elmeski, 2015; Hourani & Stringer, 2015; Romanowski et al., 2019), including Latvia.

Curriculum action research considers participants’ expectations, beliefs, values, and their understanding for framing the research: “Context, teacher perceptions and beliefs, learner aspirations and interpretations of the situation, all affect the way in which curriculum intentions are realised in practice” (Pring, 2004, p. 136). Considering theoretical and empirical insights (Chan et al., 2019; Elmeski, 2015; Hourani & Stringer, 2015; Pring, 2004; Romanowski et al., 2019; Tzianakopoulou & Manesis, 2018; Wood & Roac, 2000), it could be concluded that school leaders’ expectations, perceptions and self-perceptions, aspirations and interpretations, beliefs and values have to be explored in order to offer a more appropriate professional development programme in terms of its design and delivery.

The purpose of this research was to identify school leaders’ initial attitudes, expectations, and beliefs at the beginning of their participation in professional development training for implementing character education at school (hereinafter – the Programme). Getting a clear initial picture of those aspects was important for setting the context of a subsequent action research about the effectiveness of the Programme: the findings were intended to be used as a reference landmark for weighting participants’ judgements regarding the Programme’s feasibility and its influence on them after completion. In order to achieve this purpose, the following three research questions were addressed:

Research question 1 (RQ1): What were school leaders’ attitudes and expectations starting the Programme?

Research question 2 (RQ2): What were their initial beliefs about their knowledgeability and leadership competence in the field?

Research question 3 (RQ3): What were their initial beliefs about their role and influence on pupils’ moral growth, and about their personal moral development?

Materials and methods

Research design

This study adopted a survey research design with mixed methods. Quantitative and qualitative data were analyzed for exploring school leaders’ initial attitudes, expectations, and beliefs regarding moral growth and virtue education at the beginning of the Programme.

Participants

Thirty respondents participated in the research: six school principals and 24 vice-principals. This was a convenience sample: all participants were school leaders who voluntarily signed-up to participate in the Programme conducted by the principal investigators, after receiving an invitation from the educational authorities of their region. Regarding the demographics, the majority of them were females (93 %); their overall work experience oscillated between 4 and 44 years (M = 23.20; SD = 12.56); and their school leadership experience was between 1 and 31 years (M = 10.33; SD = 10.08). Twenty-nine participants worked in public schools and one in a private school. One participant worked in a primary school (grade 1 to 4), six in lower secondary schools (grades 1 to 9), 22 in upper secondary schools (grades 1 to 12), and one in a special education school. Almost 60% of the participants worked in schools with less than 600 pupils, but there were also four participants from a school with more than 1200 students and two from schools with less than 150 students. The diversity of participants’ professional background enriched the insights of the research.

Research instrument

A questionnaire was used for collection of qualitative and quantitative data. The questionnaire had the following sections: (1) two open-ended questions about the participants’ attitude, possible contribution and expectations starting the Programme; (2) two questions (one closed-ended and one open-ended) about the participants’ perceived knowledgeability and one open question about their perceived leadership competence in the field; (3) four open-ended questions capturing how school leaders perceived the role they have in moral education, the influence of their moral stance on students’ moral development, the need for their own personal moral growth, and the conditions under which it happens better; and (4) the demographics section.

Data collection, processing, and analysis

The questionnaire was administrated in paper form in Spring and Fall 2020 to school leading staff from Riga, Riga surroundings, and Sigulda at the beginning of the first session of the Programme. Quantitative data were processed and analyzed using MS Excel and IBM SPSS Statistics 26 software. Qualitative data were processed and analyzed using NVivo 12 software, applying a thematic analysis and open coding for analyzing the answers to open-ended questions. A combination of deductive (pre-set coding scheme) and inductive (codes generated while examining the collected data) approaches to coding was used (Linneberg & Korsgaard, 2019). In total, textual data of 2638 written words (16,343 characters) were transcribed in electronic text and analyzed to identify segments of meaning; and each segment of meaning was referenced under a code. The final codebook consisted of 62 codes grouped in 8 thematic blocks; each block was related to one of the open-ended questions (see Table 1).

Table 1. Textual data analysis: Frequencies by thematic blocks

|

RQ |

Thematic block |

Count of words |

Count of unique codes |

Count of references |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ethical considerations

For using the questionnaire, the approval for the Practitioner Inquiry in Education research was obtained at the University of Birmingham (MA “Character education” supervisor Tom Harrison, 24.01.2019). The research was also part of the postdoctoral project Arete-school (2017–2020), whose research methodology was approved by the University of Latvia Prorector of Humanities and Education Sciences, Professor Ina Druviete as being in conformity with the legislation of the Republic of Latvia and the regulations concerning research application, which include research ethics concerns (Contract No 9-14.5/272 of 02.11.2017, point 8.2 and 8.3). Participants’ informed consent was requested before participating in the survey, using a paper consent form. All respondents participated voluntarily in the research. For ensuring confidentiality, data analysis was done at the group level. For ensuring anonymity, each questionnaire had a confidential code known only by researchers.

Results

RQ1: Participants’ initial attitude, intended contribution, and expectations

The questionnaire included two open questions about participants’ intended contribution and expectations starting the Programme. In analyzing respondents’ answers to the question “How can I be useful to others during this Programme?” 41 units of meaning were referenced. Most of the references pointed to respondents’ experience and expertise (n = 23), their positive attitude (n = 6), and their desire of sharing their knowledge and ideas (n = 6). Fifty-three references regarding their expectations were identified: in most of the cases, respondents mentioned their desire to acquire new tools (n = 32), in particular new methods for working with students (n = 12) and families (n = 5), for enhancing collaboration (n = 6) and motivation at school (n = 3), and for facilitating self-growth (n = 1). Some references stressed the respondents’ desire to improve their theoretical knowledge of the field (n = 18) and to exchange experience with other participants (n = 14), in particular regarding the transmission and cultivation of values. Summarizing, the main expectation that emerged from the data was the participants’ desire to enhance their professional competence by collaborating and sharing with others, and by acquiring new knowledge and practical tools for moral education.

RQ2: Participants’ initial beliefs about their knowledgeability and leadership competence

School leaders’ knowledge about moral education concepts

Regarding the question “In your opinion, to what extent are you knowledgeable of the basic concepts of moral education (character, virtue, values, temperament, moral habits, etc.)?” at the beginning of the Programme, the mean of the data set was 5.23 with the mode of 5 (in a 7-point Likert scale). The qualitative assessment of participants’ knowledgeability was done by asking them to define “values” and “virtues” in their own words, and to explain the differences (if any) between those two concepts. Five respondents did not provide any definition; therefore, only twenty-five definitions were analyzed collaboratively by the researchers. According to the results, a solid knowledgeability regarding those notions was found in 80% of definitions, while the rest of definitions made apparent the respondents’ doubts about these concepts and their lack of awareness of the field.

School leaders’ perceived leadership competence for moral education

Analyzing their answer to the question “How competent do you feel now in the field of leadership for values and virtue education?” at the beginning of the Programme the mean of the data set was 6.85 with the mode of 7 (in a 10-point Likert scale). During the qualitative analysis, 52 references regarding participants’ perceived leadership competence were found: 29 references pointed to what makes them feel competent, e.g., their own experience (n = 12), their knowledge and personal background (n = 10), and their personal values and virtues (n = 7); and 23 references pointed to what they feel they are still missing, e.g., the ability to adapt to the rapid changes in society (n = 7), their lack of experience (n = 6), and the unavailability of effective tools for moral education (n = 4).

RQ3: Participants’ beliefs about their role and influence on pupils’ moral growth, and about their personal moral development

School leaders’ perceived role in pupils’ moral growth

Regarding the way school leaders perceived their role in pupils’ moral growth, 41 references were found. All respondents believed that they have an important role. In 46% of the references (n = 19), they perceived themselves as role models for students, colleagues, and parents. In 29% of references (n = 12), they pointed directly to their role of providing trustful communication by supporting, inspiring, and motivating students. Furthermore, 22% of references (n = 9) referred to their leadership role at the school level (managing changes, giving official support moral education, organizing the curriculum and school events, creating a school atmosphere supportive of character education, and enhancing collaboration in their institutions).

School leaders’ perceived influence of their moral stance on pupils’ moral development

Analyzing their answer to the question “Do you think that your personal moral stance, your values and virtues influence the moral development of pupils? Why? (If yes) In what way?” 31 references were found: 55 % of them (n = 17) referred to the impact they can have through the example of their own virtues; and 45% of the references (n = 14) addressed the importance of mutual relationships: speaking with pupils, being open with them about one’s feelings and values, giving them time and attention, adapting to their needs, and providing opportunities for mutual collaboration.

School leaders’ perceived need and motivations for personal moral growth

Regarding participants’ perceived need and motivations for personal moral growth, 35 references were found. All respondents excepted one believed that they need to grow as moral persons. Some of them specifically reported a desire to grow in virtue (n = 9), while others were motivated by the need to adapt to the rapid changes in society (n = 8), to get new experiences and perspectives (n = 5) and to improve self-knowledge (n = 4). Some respondents mentioned that growth is necessary in any field (n = 7), and some were motivated to grow in order to offer the best to their students (n = 2).

School leaders’ beliefs about the conditions of their own moral growth

In analyzing respondents’ answers to the question: “In what way and under what conditions does your moral development happens best? What are the main obstacles for your moral development?” 56 references were identified: 42 about moral growth facilitators, and 14 about the obstacles that hinder their moral development. “Reflecting” was the most often mentioned way of growing (n = 16), and this included individual reflection, reading, attending courses, and praying. The second most often mentioned growth facilitator was interaction with others (n = 11), including speaking with and listening to colleagues and students, collaboration, seeing good examples in others, and meeting inspiring people. The third moral growth facilitator was experience (n = 10). Some mentioned that they grow better as moral persons in a familiar environment and friendly atmosphere, where they feel confident and supported (n = 4). The main obstacles they mentioned in their growth as moral persons were a busy lifestyle (n = 6) and the presence of negative examples in society (n = 3).

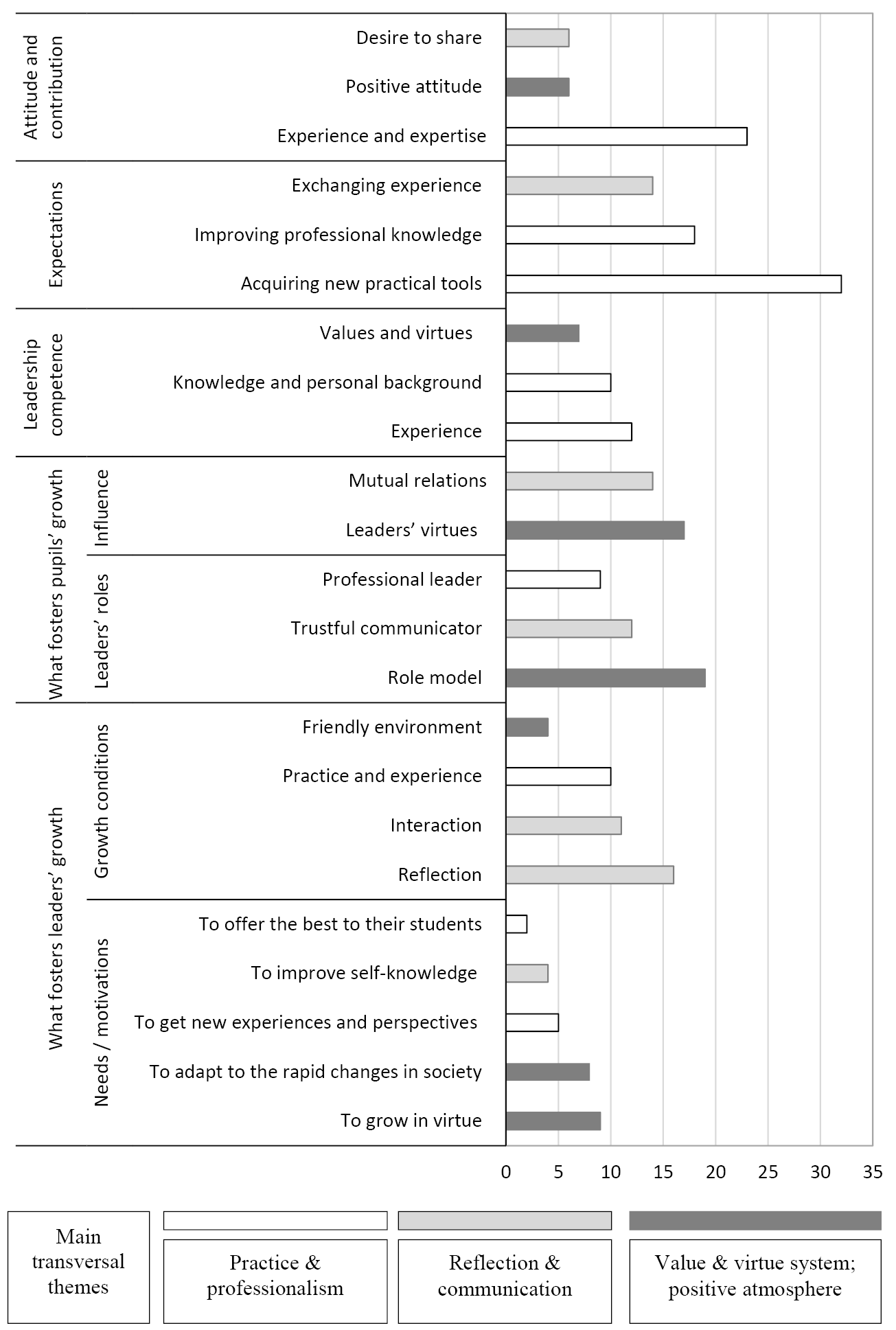

Summary of participants’ initial attitudes, expectations and beliefs

Overall, several recurrent transversal themes emerged from the exploration of participants’ initial attitudes, expectations and beliefs starting the course on character education leadership (see Figure 1). Some of them were directly related to practice and professionalism (in white): participants were self-confident about their professional experience and expertise; acquiring practical tools was one of their central expectations; and their desire of getting new experiences and perspectives as well as enhancing their professional knowledge of the field appeared both in their initial expectations and in their beliefs regarding how to grow as moral persons. Another thematic group was related to reflecting, sharing, and communicating (in light grey): participants stressed their desire to share their knowledge and ideas; they expected opportunities for exchanging experience with colleagues; and strongly believed that reflection and interaction are the most necessary conditions for their personal growth; furthermore, positive mutual relations were seen as necessary to foster pupils’ moral development. A third thematic group was related to the importance of establishing a friendly environment and atmosphere, based on a common system of values and virtues (in dark grey): participants had a positive attitude starting the course; they were motivated to grow in virtue and to adapt to the rapid changes in society for transmitting values and virtues to the young generations; and one of their strongest beliefs was the necessity for them to embody virtues and to establish a friendly atmosphere of trustful communication as a condition for pupils’ and their own moral growth.

Figure 1. Participants’ attitudes, expectations and beliefs: Frequencies of main transversal themes.

Discussion and conclusions

At the beginning of the Programme for implementing character education in Latvian schools, the majority of school leaders considered themselves as quite knowledgeable regarding moral education, and somewhat competent for leading it at school. They showed a positive attitude and open-mindedness to acquire new knowledge and skills, to share their expertise and ideas, and to grow in virtue. Their main expectations were to thrive professionally and personally by collaborating, sharing, reflecting, and acquiring new knowledge and practical tools.

Participants believed in the importance of a friendly and motivating atmosphere of mutual support and trustful communication for the success of the Programme. This finding resonates with recent research, which describes school leaders as individuals who bring together diverse networks, care about human relations and are focused on knowledge development and open, inclusive, and collaborative relationships (Elmeski, 2015, p. 13).

School leaders were aware of their role model and of the impact of their own personal values and virtues on colleagues, pupils, and parents. These findings echoed the importance of school leaders’ ethical stance and personal example stressed in recent research (Boydak Özan et al., 2017; Chan et al., 2019; Walker et al., 2017). Recent research has found that the principal’s moral role model seems to be particularly relevant for students (Fernández González et al., 2019).

Participants also mentioned a busy lifestyle, rapid societal changes, and the presence of negative examples in society as the main challenges and obstacles in feeling more competent as moral educators. This finding is coherent with Elmeski’s (2015) suggestion that “while emotional and spiritual realities provide important repositories for sustaining principals’ commitment to school improvement, physical and socio-political challenges threaten to strain their resilience” (p. 16).

Fullard and Watts (2020) recently emphasized “the role of school leaders in effectively coordinating opportunities for both staff and students to develop their character, both inside and outside of the classroom” (p. 16). The way in which this Programme for character education leadership was conceived provided a practical example about how to coordinate these opportunities effectively. The Programme was elaborated using a combination of three approaches to character education: (1) the Programme considered the participants themselves (and the instructor – principal investigator) as role models for the other participants (caught approaches); (2) lectures about leadership for character education were offered through the Programme (taught approaches); and (3) opportunities for participants’ autonomous reflection and reasoning were offered throughout the whole Programme (sought approaches).

In our data, school leaders saw their role for fostering staff and pupils’ moral growth as being related to the “caught” approaches of moral education (e.g., school leaders as role models), while school leaders’ moral growth conditions seem to include mainly “sought” approaches (e.g., individual reflection opportunities). However, given the small sample, more research is necessary for confirming this hypothesis.

As it was mentioned previously, the diversity of the professional background of school leaders provided enriching insights for the research. The research findings presented in this study were a helpful starting point for setting the context of the subsequent action research implemented in this Programme: they were used as a reference point for assessing participants’ value judgements regarding the Programme’s feasibility and its influence on them after completion. The findings can also be useful for future similar initiatives in the field, as they reveal some important aspects to be considered when organizing training courses for character education leadership.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the EU European Regional Development Fund under Grant No 1.1.1.2/VIAA/1/16/071, the postdoctoral project ‘Arete school’ (2017-2020) and the University of Latvia under Grant No ZD2010/AZ22, the research project ‘Human, technologies and quality of education’.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

Agboola, A., & Tsai, K. C. (2012). Bring character education into classroom. European Journal of Educational Research, 1(2), 163–170. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1086349.pdf

Arthur, J., Kristjánsson, K., Harrison, T., Sanderse, W., & Wright, D. (2017). Teaching character and virtue in schools. London: Routledge.

Avolio, B. J., & Gardner, W. L. (2005). Authentic leadership development: Getting to the root of positive forms of leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 16(3), 315–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2005.03.001

Bass, B. M., & Steidlmeier, P. (1999). Ethics, character, and authentic transformational leadership behavior. The Leadership Quarterly, 10(2), 181–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1048-9843(99)00016-8

Berkowitz M. W., Battistich V. A., & Bier M. C. (2008). What works in character education: What is known and what needs to be known. In L. P. Nucci & D. Narvaez (Eds.), Handbook of moral and character education (pp. 414–431). Routledge.

Berkowitz, M. W. (2011). Leading schools of character. In A. M. Blankstein & P. D. Houston (Eds.), The soul of educational leadership series: Vol. 9. Leadership for social justice and democracy in our schools (pp. 93–121). Corwin.

Berkowitz, M. W., & Bier, M. C. (2006). What works in character education: A research-driven guide for educators. Character Education Partnership.

Berkowitz, M. W., Bier, M. C., & McCauley, B. (2017). Toward a science of character education: Frameworks for identifying and implementing effective practices. Journal of Character Education, 13(1), 33–51. https://www.samford.edu/education/events/Berkowitz-Bier--McCauley-JCE-2017.pdf

Boydak Özan, M., Yavuz Özdemir, T., & Yirci, R. (2017). Ethical leadership behaviours of school administrators from teachers’ point of view. Foro de Educación, 15(23), 161–184. https://doi.org/10.14516/fde.520

Cabinet of Ministers. (2016a). Kārtība, kādā akreditē izglītības iestādes, eksaminācijas centrus un citas Izglītības likumā noteiktās institūcijas, vispārējās un profesionālās izglītības programmas un novērtē valsts augstskolu vidējās izglītības iestāžu, valsts un pašvaldību izglītības iestāžu vadītāju profesionālo darbību [Procedures for the accreditation of educational institutions, examination centres, other institutions specified in the Education law, general and vocational education programmes and the evaluation of professional activities of educational institutions managers], CoM Regulation No 831, 20.12.2016, Prot. No 69 27.§ https://www.vestnesis.lv/op/2016/250.20

Cabinet of Ministers. (2016b). Izglītojamo audzināšanas vadlīnijas un informācijas, mācību līdzekļu, materiālu un mācību un audzināšanas metožu izvērtēšanas kārtība [Guidelines for the upbringing of learners and the procedure for evaluating information, teaching aids, materials and teaching/learning and upbringing methods], CoM Regulation No 480, 15.07.2016, Prot. No 36 34.§ https://www.vestnesis.lv/op/2016/141.4

Cabinet of Ministers Regulation regarding Valsts tiešās pārvaldes iestāžu vadītāju atlases kārtība [A procedure for selecting the heads of direct administration state institutions], CoM Regulation No 293, 09.06.2015, Prot. No 28 17.§ (2015). https://www.vestnesis.lv/op/2015/116.6

Chan, T. C., Jiang, B., Chandler, M., Morris, R., Rebisz, S., Turan, S., Ziding Shu, Z., & Kpeglo, S. (2019). School principals’ self-perceptions of their roles and responsibilities in six countries. New Waves Educational Research & Development, 22(2), 37–61. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1243030.pdf

Character.org. (2016). Eleven principles of effective character education: A framework for school success. Character.org. https://www.ethicsed.org/uploads/8/9/6/8/89681855/eleven_principles_july_2016.pdf

Crow, G., Day, C., & Møller, J. (2017). Framing research on school principals’ identities. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 20(3), 265–277. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2015.1123299

Deslandes, R. (2019). A framework for school-family collaboration integrating some relevant factors and processes. Aula Abierta, 48(1), 11–18. https://doi.org/10.17811/rifie.48.1.2019.11-18

Elmeski, M. (2015). Principals as leaders of school and community revitalization: a phenomenological study of three urban schools in Morocco. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 18(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2013.815803

Fernández González, M. J. (2019). Skolēnu morālā audzināšana Latvijas skolās: vecāku, skolotāju, topošo skolotāju un skolu un izglītības pārvalžu vadītāju viedokļi [Moral education of pupils in Latvian schools: The views of parents, teachers, future teachers, heads of schools and education boards]. LU PPMF Pedagoģijas zinātniskais institūts. http://dspace.lu.lv/dspace/bitstream/handle/7/46498/Zi%20ojums_Skol%20nu%20mor%20l%20%20audzin%20%20ana%20Latvijas%20skol%20s.pdf?sequence=1

Fernández González, M. J., Pīgozne, T., Surikova, S. and Vasečko, Ļ. (2019). Students’ and staff perceptions of vocational education institution heads’ virtues. Quality Assurance in Education, 28(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1108/QAE-11-2018-0124

Fernández González, M. J. (2020). Assessment of a pilot programme for supporting principals’ leadership for character education in Latvian schools. Master thesis submitted in partial requirement of MA in Character Education. Jubilee Centre for Character and Virtues, University of Birmingham. https://dspace.lu.lv/dspace/handle/7/52875

Francom, J. A. (2013). What high school principals do to develop, implement, and sustain a high functioning character education initiative. University of Montana, Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=11795&context=etd

Francom, J. A. (2016). Roles high school principals play in establishing a successful character education initiative. Journal of Character Education, 12(1), 17–34.

Fullard, M., & Watts, P. (2020). Leading character education in schools: An online CPD programme. Jubilee Centre for Character and Virtues, University of Birmingham. https://www.jubileecentre.ac.uk/userfiles/jubileecentre/pdf/Research%20Reports/CPD_Report.pdf

Hourani, R. B., & Stringer, P. (2015). Professional development: perceptions of benefits for principals. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 18(3), 305–339. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2014.904003

Huggins, K. S., Klar, H. W., Hammonds, H. L., & Buskey, F. C. (2017). Developing leadership capacity in others: An examination of high school principals’ personal capacities for fostering leadership. International Journal of Education Policy & Leadership, 12(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.22230/IJEPL2017v12n1a670

Johnson, L. J., Pugach, M., & Hawkins, A. (2004). School-family collaboration: A partnership. Focus on Exceptional Children, 36(5), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.17161/foec.v36i5.6803

Larocque, M., Kleiman, I., & Darling, S. M. (2011). Parental involvement: The missing link in school achievement. Preventing School Failure, 55(3), 115–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/10459880903472876

Linneberg, M. S., & Korsgaard, S. (2019). Coding qualitative data: A synthesis to guide the novice. Qualitative Research Journal, 9(3), 259–270. https://doi.org/10.1108/QRJ-12-2018-0012

Murray, E. D., Berkowitz, M. W., & Lerner, R. M. (2019). Leading with and for character: The implications of current character education practices for military leadership. Journal of Character and Leadership Development, 6(1), 33–42. https://jcli.scholasticahq.com/article/7520-leading-with-and-for-character-the-implications-of-character-education-practices-for-military-leadership

Navarro, K. C., Johnston, A. E., Frugo, J. A., & McCauley, B. J. (2016). Leading character: An investigation into the characteristics and effective practices of character education leaders. University of Missouri–St. Louis, UMSL Graduate Works. https://irl.umsl.edu/dissertation/90

Peña, D. C. (2000). Parent involvement: Influencing factors and implications. The Journal of Educational Research, 94(1), 42–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220670009598741

Pring, R. (2004). Philosophy of educational research. Continuum.

Raborife, M. M., & Phasha, N. (2010). Barriers to school-family collaboration at a school located in an informal settlement in South Africa. Cypriot Journal of Educational Sciences, 5, 84-93. https://www.academia.edu/34804715/Barriers_to_school-family_collaboration_at_a_school_located_in_an_informal_settlement_in_South_Africa

Romanowski, M. H., Sadiq, H., Abu-Tineh, A. M., Ndoye, A., & Aql, M. (2019). The skills and knowledge needed for principals in Qatar’s independent schools: Policy makers’, principals’ and teachers’ perspectives. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 22(6), 749–773. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2018.1508751

SEQS, State Education Quality Service. (2016). Metodiskos ieteikumus profesionālās izglītības un vispārējās izglītības iestāžu pašvērtēšanai [Methodological recommendations for self-evaluation of vocational education and general education institutions]. http://viaa.gov.lv/library/files/original/06_IKVD_Metod_iet_pasvertesanai.pdf

Skola2030. (2017). Izglītība mūsdienīgai lietpratībai: mācību satura un pieejas apraksts [Education for modern competence: description of study content and approach]. http://www.izm.gov.lv/images/aktualitates/2017/Skola2030Dokuments.pdf

The National Society. (2017). Leadership of character education: Developing virtues and celebrating human flourishing in schools. The Church of England, Foundation for Educational Leadership. https://cofefoundation.contentfiles.net/media/assets/file/CEFEL_LeadershipCharacter_Report_WEB.pdf

Tzianakopoulou, T., & Manesis, N. (2018). Principals’ perceptions on the notion of organizational culture: The case of Greece. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 6(11), 2519–2529. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujer.2018.061117

Wahyono, I., Widodo, J., & Sumaryanto, T. (2018). The optimization of headmaster’s role in actualizing character education at vocational private high school. AIP Conference Proceedings, 1941(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5028105

Walker, M., Sims, D., & Kettlewell, K. (2017). Leading character education in schools: Case study report. National Foundation for Educational Research in England and Wales. https://www.nfer.ac.uk/publications/pace02/pace02.pdf

Wood, R. W., & Roach, L. (2000). Administrators’ perceptions of character education. Education, 120(2), 213–238.