Archaeologia Lituana ISSN 1392-6748 eISSN 2538-8738

2022, vol. 23, pp. 120–134 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/ArchLit.2022.23.7

Rings of Power or in Search of Early Elites

Igor Manzura

National Museum of History of Moldova

31 August 1989 Street, 121a, MD-2012, Chișinău, Republic of Moldova

ingvarmnsr6@gmail.com

Abstract. The article discusses the problem of identification of prehistoric elites on the example of the Usatovo culture. Archaeological evidence allows us to discern in the culture three separate strata or classes which are conditionally designated as the Nobles, the Honoured, and the Commoners. Social elite represented a core within the noble class. It is distinguished by specific attributes which illustrate its attempts to resolve one of the most complex problems of any elite – to reconcile tension between “universalism” and “particularism”. The first quality is realized in ritual performance through manipulation of material objects whereas the second one is realized by means of sumptuary customs along with other methods. The emergence of the elites in the Usatovo culture became possible due to specific combination of objective factors which were successfully utilized by new social leaders.

Key words: North Pontic region, Early Bronze Age, the Usatovo culture, cultural anthropology, complex society, social hierarchy, elites.

Galios žiedai arba ankstyvojo elito paieškos

Anotacija. Straipsnyje, remiantis Usatovo kultūros pavyzdžiu, aptariama priešistorinio elito identifikavimo problema. Archeologiniai įrodymai leidžia šioje kultūroje išskirti tris sluoksnius, arba klases, kurie sąlygiškai įvardijami kaip didikai, garbingieji ir paprastieji. Elito sluoksnio Usatovo kultūroje atsiradimas tapo įmanomas dėl savito objektyvių veiksnių derinio, kurį sėkmingai panaudojo nauji socialiniai lyderiai.

Reikšminiai žodžiai: Šiaurės Pontiko regionas, ankstyvasis bronzos amžius, Usatovo kultūra, kultūrinė antropologija, kompleksinė visuomenė, socialinė hierarchija, elitas.

____________

Received: 07/11/2022. Accepted: 02/12/2022

Copyright © 2022 Igor Manzura. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

If you don’t know what you’re looking for,

how will you know what you’ve found?

Eric McCormack. The Dutch Wife

1. Introduction

The notion of elite is firmly anchored in prehistoric archaeology. Traces of elites are found in very different chronological and archaeological contexts: in early Neolithic settlements of Anatolia (Özdoğan, 2018), among early Eneolithic inhabitants of the North Pontic steppes (Rassamakin, 1999, p. 102), in Bronze Age Central Europe (Harding, 2015) and Anatolia (Lichter, 2018), etc. Probably only Palaeolithic hunters and foragers still remained without own elite although perhaps it is just a matter of time. One gains impression that the elites as a social category uninterruptedly accompany long period of human history, at least from the early Neolithic to modern times.

Such broad usage of the notion inevitably generates a sceptical attitude to its usefulness for prehistoric studies (Hansen, 2012, p. 213). And this scepticism is quite understandable, at least for two reasons. First, as a rule, authors don’t try to explain why uncovered archaeological material should demonstrate the presence of nothing else but the elites, and which specific features correspond precisely to this social category. Secondly, manifestations of the elites are recognized in such divergent archaeological contexts (settlements, graves, fortifications, sanctuaries, hoards, etc.) that it is very difficult to bring this variable evidence under one blanket definition. In many situations any signs of social differentiation in archaeological record are explained as an indication of elite activities although this differentiation could have quite different nature. This problem seems to be conditioned by the absence of a definition and clear ideas about main characteristics of elite as a social entity in prehistoric archaeology. It echoes to some extent similar problems in other humanitarian disciplines, which are occupied with elite theme – sociology and cultural anthropology.

The concept of elite was borrowed by archaeology from sociology where elaboration of elite theory has already sufficiently long history. Many sociologists and anthropologists recognize the inherent vagueness of the concept and its changing meaning and uses in historical retrospective (Marcus, 1983, p. 7–8; Shore, 2002, p. 3–4, 9–10). Prior to the nineteenth century, the term “elite” had a more restricted sense and was mainly used in theological meaning as those formally selected or chosen by God. With transition to mass society and national states with more liberal social orders, the elite is usually conceived as a group of individuals who occupy command posts and possess power, wealth and fame (Wright Mills, 1956, p. 13). Such groups are the major source of change with relevant levels of social organization (Marcus, 1983, p. 9). In cultural anthropology, the elites are defined as those who occupy the most influential positions or roles in the important spheres of social life. They can be leaders, rulers and decision makers whose activities and decisions crucially shape what happens in the wider society (Shore, 2002, p. 4).

However, leaders and decision makers, formal or informal, exist in societies of any organizational level. They can be found even in baboon troops. It is not enough to be a leader in order to become elite. Although some anthropologists believe that elites can be traced in all cultures and societies (Haller, 2012, p. 87), this social category should be mostly related to complexly organized and well-structured social entities, but not necessarily with hierarchical order. And it is not surprising that most of anthropological studies of elites are concerned with sufficiently complex societies where state and class formation is weak (e.g., African states, Latin America, India), but not with those at the local group level (Marcus, 1983, p. 20–21). That is why there is a sense to look for elites in prehistoric past preferably among those cultural units which demonstrate an appropriate level of complexity with distinctive social strata.

Despite its inherent uncertainty and versatility, the concept of elites can be disclosed through main characteristics which are considered in numerous sociological and anthropological works. As G. E. Marcus maintains (1983, p. 9), organization of powerful groups which can be treated as elites can be mapped and described. As a causal agency, the elites should possess two important interconnected qualities: a high degree of independency and high level of creativity. The first quality is especially valuable in formative phase of elites when existing social order has to be reformed or displaced. Indeed, if the elites are not able to follow prescribed rules, they change these rules. Independence could be reached by different means including direct coercion or sacralization of social power and position or using both these methods and other ones. Proper choice and combination of needed social instruments has depended on other important quality – creativity. The same quality was vitally necessary for organization of effective economic and social management and construction of well-balanced social structure which could be resilient to inner and external challenges. In the course of time, creative ability of the elites loses its earlier potential since more energy is applied to maintenance of established order in spite of permanently changing conditions. Any slayer of the Dragon eventually becomes the Dragon himself, it is almost unalterable rule. In this case, we usually speak about degradation or stagnation of the elites. It is quite difficult to trace the process of formation and decay of social patterns in archaeological record, although stability and recurrence of some combinations in material culture for a long time can evidence for fossilization of certain social system and its forthcoming disintegration.

One of the main problems in elite studies is determination of boundaries between this social group and subordinate population (Wright Mills, 1956, p. 18; Marcus, 1983, p. 21–22). It is especially difficult to draw such boundaries on the basis of archaeological material. Possible hints can be found in sociological theory of elites. According to Wright Mills, the elite cannot be conceived as the whole upper class or social layer, it rather constitutes the inner circle or core of “the upper social classes” (Wright Mills, 1956, p. 11). Consequently, our search of ancient elites in prehistoric period should be concentrated on cultural entities with clear social gradation exemplified by appropriate arrangement of relevant material traits where such social core can be identified.

Another key question is related to way of reproduction of elites over time. In modern liberal societies, the recruitment of new members of elites is not restricted by class privileges, and any citizen is able to reach prestige position in higher social echelons in different fields of activities, especially in intellectual sphere. Of course, some individuals have better chances to make a successful career from the beginning, due to easier access to better education, financial support and personal relations, but talented people usually have always a possibility to realize their ambitions and potential. In ancient and feudal societies, social elites could be reproduced only on hereditary principles or/and on the basis of contractual marriages within restricted circle of noble families. In earlier prehistoric time (the late Palaeolithic, the Mesolithic and the Neolithic) with its egalitarian norms, basic age/sex social differentiation and prescribed status, such system probably was not practiced, but in later periods, especially in the Bronze Age, occurrence of hereditary social status can be recognized. In turn, traits of the hereditary status, especially well represented in various aspects of burial rite, can signalize existence of social elites.

In order to maintain dominance over dependent groups and gain public support, social elites need to resolve contradiction between “universalism” and “particularism” (Cohen, 1981: cited after Shore, 2002, p. 2). On the one hand, the elites must demonstrate that they express interests of all subordinate groups and their activities have universal character for the benefit of the whole society. According to A. Cohen, this goal is achieved by means of mystique, dramatic performance and rhetoric strategies. Of course, it is difficult to assess rhetoric exercises of prehistoric elites in archaeology. However, there is a hope that silent rhetoric of ideas expressed by means of material culture will be eloquent enough to discern efforts of elites to express their universal nature.

The particularism or exclusivity, according to Marcus (1983, p. 11–12), elites have to base on special arrangement of regulations, norms and practices which are recognized by both representatives of this group and the masses. Different elements of material culture also can have special significance, particularly those with symbolic connotation. In prehistoric period and in later religious societies, exclusive status of elites could be complemented by restricted access to sacral knowledge. In other words, elites must create specific type of culture – elite culture – which could keep separating boundaries inviolable, cultivate consciousness and cohesion among members of the group as well as serve as means of propaganda of their unquestionable significance for subordinate population. Invention of specific social mechanisms in order to maintain exclusivity of elites provides an additional evidence for rather later emergence of this phenomenon in prehistory since egalitarian ideology of early farmers had to preclude existence of such legitimately recognizable regulations. Obvious distinctions in spatial distribution of some traits of material culture in early agricultural settlements indeed can signalize relations of social inequality. These relations, however, could be caused by different circumstances and not necessarily were conditioned by efforts of elites to keep their exclusive positions. For instance, division of villages into two parts, with apparent distinctions in material culture in the extreme Southern Highlands of Madagascar, was determined by origins of inhabitants. The western (evil) periphery was dwelled by newcomers or “impure people”, whereas the eastern periphery was occupied by local population or “pure people” (Evers, 2002, p. 161–162). However, all settlers from the eastern periphery cannot be considered as a social elite. This part of society included families of noble descent (andriana), which can be treated as local elite. Therefore, in material record, which is concerned by archaeology, only presence of clear signs of specific elite culture can testify existence of such social category.

Thereby, in search of early elites in prehistoric Europe or elsewhere, special attention should be paid to those archaeological entities which can reveal apparent attributes of an elite culture since any elite cannot exist without such culture in its mental and material embodiment. The most evident traces of this type of culture can be found on the territory of the North-West Pontic region in the middle of the 4th millennium BC.

2. Discussion

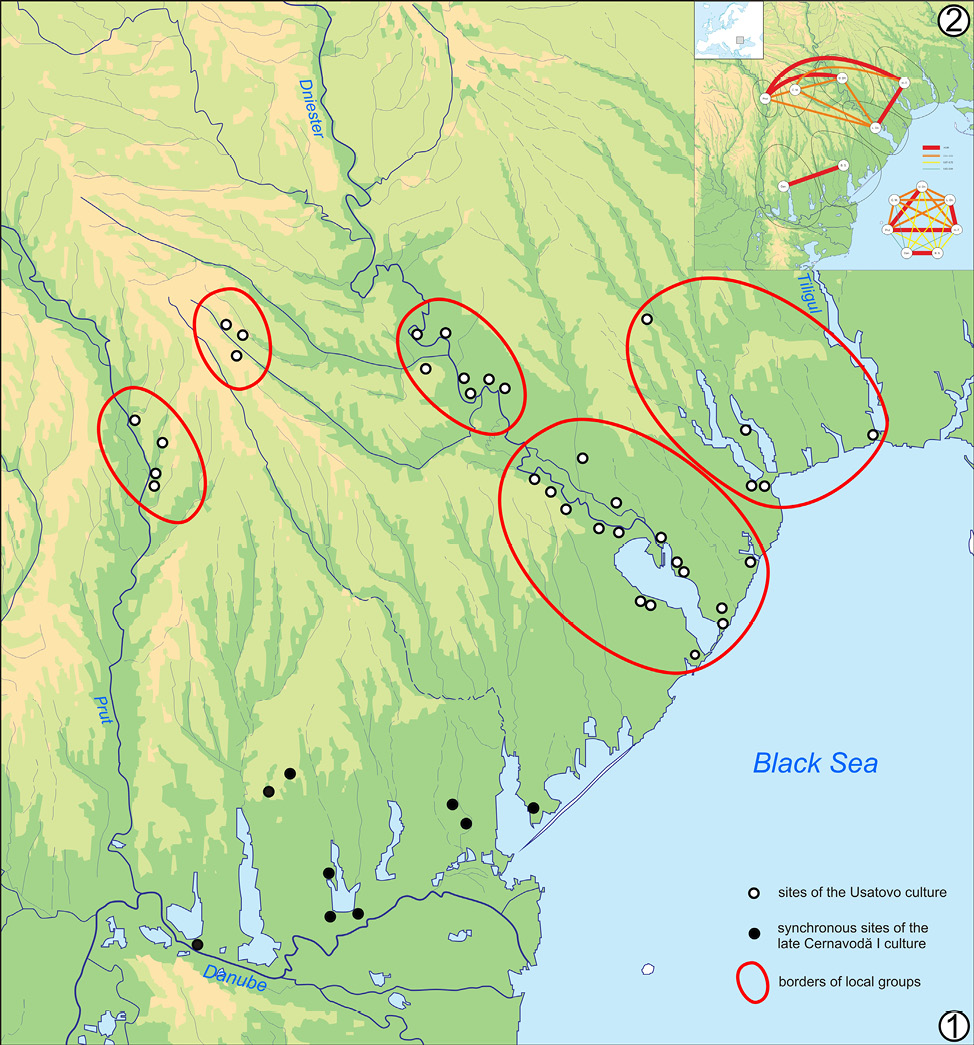

In later prehistory, the Usatovo culture located in the North-West Pontic region can be considered as one of the best examples of social organization based on activities of elites. The culture has been quite comprehensively characterized in a number of works (Збенович, 1974; Патокова, 1979; Дергачев, 1980, p. 103–111; Петренко, 1989; Петренко, 2013b; Dergačev, 1991, p. 13–17, 41–77; Petrenko, 2008; Manzura, 2020) which give sufficiently complete ideas about its basic attributes, chronology, emergence, inner structure and connections. In the last years, main changes in studies of the culture were introduced into the attribution of some cemeteries or isolated burials, as well as spatial distribution of sites and areal borders (Manzura, 2020, p. 74). Some burial sites previously considered to be of the Usatovo type were assigned either to the earlier Cernavodă I culture or to the later Zhivotilovka–Volchanskoe type. Additionally, it has been recognized that the littoral part of the Danube/Prut and Dniester interfluve and the area around the Danubian lakes in the third quarter of the 4th millennium BC was occupied by not the Usatovo culture but the later Cernavodă I culture (Fig. 1, 1). Correlation of different types of pottery ornamentation from the 4th millennium BC (Fig. 1, 2) revealed the closest links between sites within this territory and quite weak coupling with other parts of the North-West Pontic region.1 According to absolute chronology, the Usatovo culture should be dated approximately to the time span between 3500 and 3250/3200 BC and can be divided into two periods.

Fig. 1. The North-West Pontic region in the third quarter of the 4th millennium BC: 1 – distribution of sites of the Usatovo culture; 2 – bond strength between different local cultural subdivisions within the region in the 4th millennium BC on the base of ornamentation classification.

1 pav. Šiaurės vakarų Pontiko regionas IV tūkstm. pr. Kr. trečią ketvirtį: 1 – Usatovo kultūros objektai; 2 – ryšių tarp skirtingų vietinių kultūrų regione IV tūkstm. pr. Kr. stiprumas remiantis ornamentikos klasifikacija

The structure of the Usatovo burial sites is of special interest for the subject of this study. Three recognizable categories of sites can be discerned within each period. They are especially distinctive in the Lower Dniester zone and in the Dniester–Tiligul interfluve, whereas in the Lower Prut area such distinctions are expressed not so apparently.

The first category embraces cemeteries which consist of earthen tumuli with complex stone constructions like cromlechs, cairns, pavements, anthropomorphic and zoomorphic steles, large slabs with engraved depictions of humans and animals, a kind of altars in form of slabs with bowl-like holes, etc. These traits are accompanied by such attributes as big burial chambers with the size which much exceeds the need for placement of grave goods, large numbers of prestigious painted pottery, various metal objects as well as ornaments or symbols of a high social status made of precious and exotic material (silver, glass, coral, lignite, alabaster, and amber). A specific combination of bronze tools and weapons is characteristic only for this category of burial sites. It includes daggers, adzes or flat axes, chisels and awls. In some specific cases this set is complemented by such items as long punches and a massive hammer-axe but sometimes it is reduced to a packet consisting of a dagger, an adze and an awl or a dagger and an adze. Necklaces or anklets composed of pierced deer teeth are also attributes only of this group of sites.2 A few burial sites can be assigned to the first category. These are the kurgan cemetery I at Usatovo–Bolshoy Kuyalnik (Патокова, 1979, p. 43–76), the cemetery at Purcari (Яровой, 1990, p. 41–132), isolated tumulus at Aleksandrovka (Петренко, Бейлекчи, 2004; Petrenko, Bejlekchy, 2006)3 and perhaps a tumulus at Tudora (Мелюкова, 1962) where the central grave was destroyed but some metal items survived as well as a lateral grave with a lavish inventory.

The second category of burial sites is represented by tumuli which can have complex surface stone structures (e.g., the kurgan cemetery II at Usatovo) (Патокова, 1979, p. 76–85) or some additional constructive elements, for instance, the ditches around mounds at the Mayaki cemetery (Петренко, 2013b, p. 177). Burial pits are in general smaller whereas the quantity of painted pottery is less than in the sites of the first category. As a rule, graves of the second category contain similar types of metal objects, but bronze chisels, long punches or silver ornaments are absent there. Unlike burials of the first category, a specific compound dagger-adze-chisel-awl is not evidenced in this group. Similarly, symbols of status made of exotic and rare material are represented in lesser quantity. The second category is exemplified by such burial sites as the cemeteries at Mayaki (Патокова, Петренко, 1989), Sadovoe (Малюкевич et al., 2017, p. 9–33), Zatoka (Черняков, 2004) and the kurgan cemetery II at Usatovo (Патокова, 1979, p. 76–85).4

The third group of sites consists of simple burial mounds with no additional stone constructions and flat cemeteries. It is distinguished by small-sized burial pits, a strong predominance of coarse pottery, extremely rare small metal finds and total absence of exotic adornments or symbols of a high social status, although the quantity of vessels in graves can be quite significant, up to 8–9 items. Such cemeteries were studied at Usatovo–Bolshoy Kuyalnik (Патокова, 1979, p. 111–143), Yasski (Петренко, Алексеева, 1994), Mologa (Малюкевич et al., 2017, p. 34–54), etc.

The division of the Usatovo-type cemeteries into three distinctive groups can apparently testify to the existence of certain social structure in the Usatovo culture which could be composed of at least three social strata. The upper social layer is represented by cemeteries of the first category where supreme leaders with members of their families or lineages as well as representatives of local nobility could be buried. In these cemeteries, specifically, we can note special concentration of symbols of the highest status and rank, including special sets of metal objects, silver ornaments and exotic or rare materials. The second social stratum exemplified by cemeteries of the second group is probably related to the category of honoured people, some of them, perhaps, being concerned with sacerdotal functions (Патокова, 1979, p. 85). Graves of this group contain some attributes of a high status or rank, for instance, bronze daggers and other metal things, necklaces of glass or lignite beads or hair rings. Unlike in the case of the graves of the first group, however, hair rings are made solely of bronze/copper. The third, the lowermost social layer had to be related to simple commoners involved in diverse economic activities and subordinate to upper strata. Actually, no traces of ranking are evidenced among the deceased interred in burials of the third group. Some distinctions in grave goods could be conditioned by sex/age differentiation and economic or household activities. In some graves, tools for agriculture, weaving, wood and leather working were present, which perhaps could symbolize sort of occupation of their owners.

A series of burials in the first group of cemeteries deserves special attention. They can be treated as clear example of elite’s attempts to reconcile tension between ‘universalism’ and ‘particularism’ by means of manipulation with objects of material culture. Such evidence was uncovered in central graves in kurgan 12 in the 1st kurgan cemetery at Usatovo, kurgan 1 at Purcari and the Aleksandrovka kurgan. Although the burials differ in some items of grave goods, the main core of objects is very similar in all three cases.

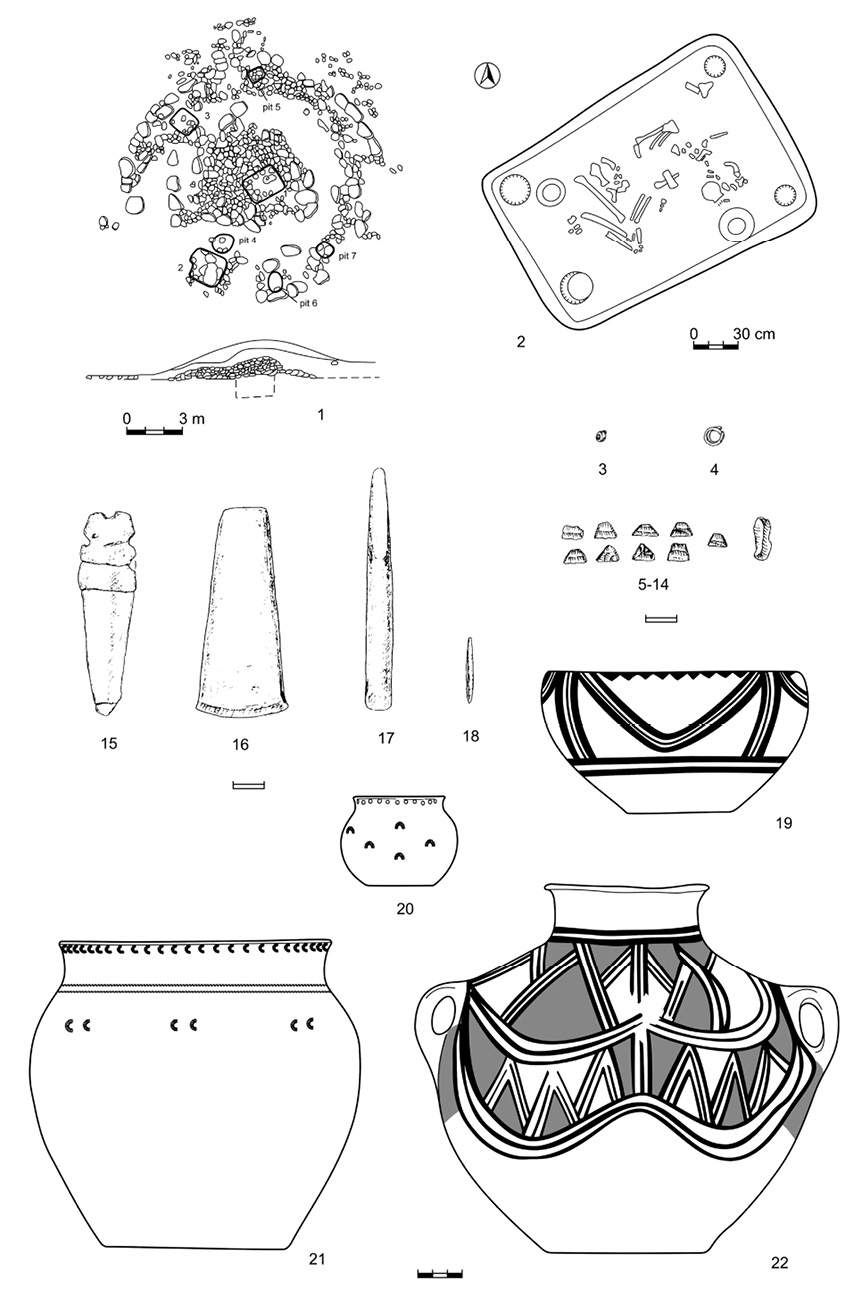

Kurgan 12 in cemetery I at Usatovo contained four burials and four cult pits (Fig. 2, 1). The central grave was a trapezoid chamber with four small pits in corners covered with a massive stone slab. A stone cairn covered by earthen layer was built above the grave. The deceased was buried in a crouched position on the left side with the head to north-east (Fig. 2, 2). The grave inventory consisted of numerous and various things. Stone tools are represented by several microlithic trapezes and one small blade (Fig. 2, 3–12) which, according to trace evidence, are inserts for a composite sickle or a harvesting knife (Петренко et al., 1994, p. 43). Metal tools include an adze, a chisel and an awl (Fig. 2, 16–18). The adze and the chisel could be used for carpenter’s work whereas the awl can be considered as a tool for leather working. V. Petrenko has suggested that adzes and chisels could be additionally designated for dressing of stone and engraving on slabs (Петренко, 2013a, p. 150). A bronze dagger (Fig. 2, 15) can be assigned to the category of weapons. Two silver hair rings (Fig. 2, 13, 14) were probably symbols of a high social status. At Usatovo, such rings occur only in graves of kurgan cemetery I. Four vessels were put in the grave: two of them were ornamented with dark-brown and red painting (Fig. 2, 19, 22), whereas the other two were made of shell-tempered clay and decorated by corded design (Fig. 2, 20, 21). The grave in question is considered to be the richest in all three cemeteries at Usatovo–Bolshoy Kuyalnik according to its inventory.

Fig. 2. The kurgan cemetery at Usatovo–Bolshoy Kuyalnik, kurgan 12, central grave (after Dergačev, 1991).

2 pav. Usatovo-Bolshoy Kuyalnik kurganiniai palaidojimai, kurganas Nr. 12, centrinis kapas (pagal Dergačev, 1991)

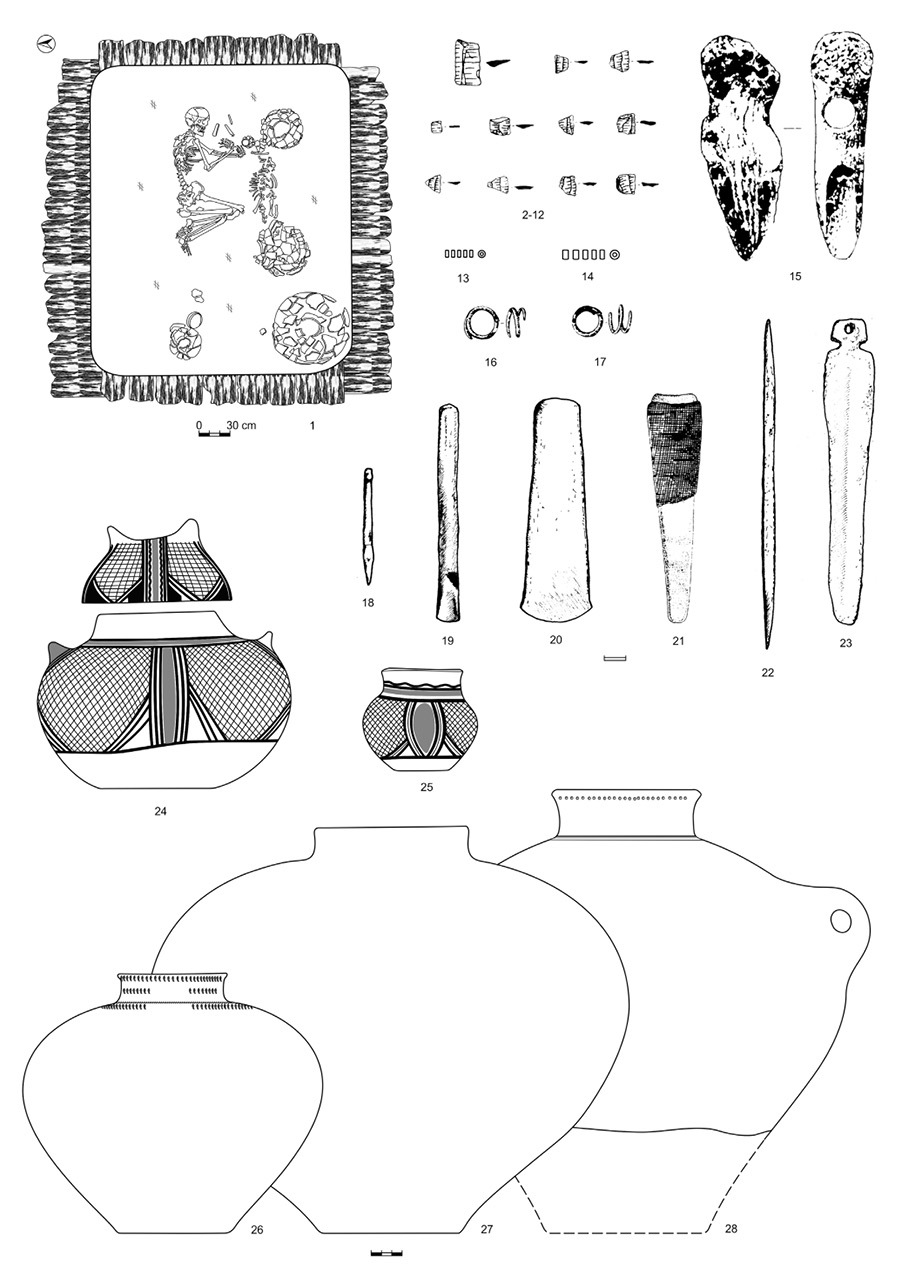

A very similar burial was uncovered in kurgan 1 at Purcari. It was arranged in a spacious rectangular pit covered with logs where the deceased was laid in a crouched position on the left side with eastern orientation (Fig. 3, 1). Grave goods consisted of tools, weapons, ornaments, and clay vessels. Tools include flint microlithic inserts for a sickle, according to trace evidence (Петренко et al., 1994) (Fig. 3, 2–12), and a packet of bronze objects: an adze, a chisel, a punch, an awl, and a knife (Fig. 3, 18–22). The weapon set embraces a bronze dagger (Fig. 3, 23) and an antler hammer (Fig. 3, 15). Ornaments are represented by two silver rings found near the skull (Fig. 3, 16, 17) and a kind of a headdress composed of about 200 big bone (?) and small lignite beads (Fig. 3, 13, 14). Additionally, the grave contained two fine painted vessels with a lid and three coarse vessels (Fig. 3, 24–28). A carcass of a sheep without the head was disposed in front of the deceased. A double cult pit with remains of sacrificial animals (a sheep, a horse and two bulls of different age) and several human bones were situated in two meters east of the grave.

Fig. 3. The kurgan cemetery at Purcari, kurgan 1, central grave (after Яровой, 1990).

3 pav. Purcari kurganiniai palaidojimai, kurganas Nr. 1, centrinis kapas (pagal Яровой, 1990)

Actually, almost the same combination of burial traits is evidenced in the kurgan at Aleksandrovka. The burial mound 3.5 m high covered 6 graves and two cult pits of the Usatovo culture and was composed of seven interlaced stone and earthen layers. A 2-meter-high cairn was in the core of the burial mound. The rectangular pit of the central grave was covered by a massive slab with weight of about 1.5 tons. The skeleton of a male was laid in a crouched position on the left side with his head to north-east (Fig. 4, 1). The tool kit consists of a stone pestle or grinder (Fig. 4, 24), several microlithic trapeziums probably from a sickle (Fig. 4, 16–23), two bronze adzes (Fig. 4, 26, 27), a punch (Fig. 4, 13), an awl (Fig. 4, 14). Weapons include a bronze shaft-hole hammer-axe (Fig. 4, 25), a bronze dagger (Fig. 4, 12) and an antler hammer (Fig. 4, 28). Symbols of status or rank are represented by five silver hair rings (two of them are not preserved) (Fig. 4, 2–4), two silver multi-coiled pendants (Fig. 4, 5, 7), a simple silver ring (Fig. 4, 6), a horn ring (Fig. 4, 9), and a necklace composed of lignite and coral beads (Fig. 4, 8, 10). The pottery set consists of two painted vessels and a lid (Fig. 4, 29, 30) and three vessels made of shell-tempered clay (Fig. 4, 31–33). The part of a sheep carcass without the head was placed on a wooden dish in front of the deceased. A bronze knife (Fig. 4, 11) was put together with remains of the sheep. The central grave in the kurgan at Aleksandrovka is considered to be the richest one in the Usatovo culture (Petrenko, Bejlekchy, 2006, 259). Other graves from this kurgan also had quite rich inventory, including fine pottery and various objects made of metal and exotic material.

Fig. 4. The kurgan at Aleksandrovka, central grave (1 – photo by V. Petrenko; 2–33 – photos by author).

4 pav. Kurganas Aleksandrovkoje, centrinis kapas (1 – V. Petrenko nuotrauka; 2–33 – autoriaus nuotraukos)

Despite some distinctions, all three burials discussed above are joined by a series of attributes with a great symbolic significance. The combination of their grave offerings probably had to express the idea of universalism and comprehensive control of all domains of social and economic activities practiced in this society. This idea is conspicuously illustrated by thorough selection of tools, weapons and symbols of social status exemplified by adornments. Indeed, specific combination of tools could signify a patronage over such economic occupations as agriculture and stockbreeding as well as wood, stone and skin working. The coverage of all main categories of metal objects in graves can testify to control of metalworking too, although specialized tools for this craft are not found. Taking into account such extensive scope of diversified economic activities expressed by tools, it can be suggested that supreme leaders could play a role of main redistributors of products, sources and services in this society. Concentration of exotic materials within the richest cemeteries could also symbolize a control of external relations, in addition.

It is worth noting that even composition of vessels demonstrate obvious similarity, especially in graves from Purcari and Aleksandrovka (Fig. 3, 24–28; 4, 29–33). Sets of vessels consisted of painted amphorae with lids, big amphorae, small pots and two big shell-tempered pots. The grave at Usatovo contained a painted bowl instead of an amphora with a lid, but the general combination of vessels is similar. Such repeated arrangement of vessels can probably express the same idea of universal order.

Two more social functions can be discerned according to distribution of grave goods in the burials under consideration. In the graves at Purcari and Aleksandrovka, the deceased were accompanied by carcasses of sheep which can be regarded as sacrificial animal. Moreover, at Aleksandrovka, a bronze knife was laid along with the carcass. Consequently, the knife can be treated as a ceremonial tool designated specially for sacrifice. In this context, the buried person appears as a slayer of the sacrificial animal or as a figure with priestly authority. Another social domain is documented by presence of weapons in the graves, which can testify to control of warrior function as well. It is worth noting that, in general, the burials in question cannot be considered ‘over-equipped’ in S. Hansen’s terminology (Hansen, 2002). Undoubtedly, well thought-out selection of singular things with clear symbolic meanings reflects rather rational approach to arrangement of grave goods. Main symbolic discourse embodied in such arrangement is related to the idea of universalism personified by buried individual and social position which it occupied during the lifetime. The same idea could be also exemplified, for instance, by specific selection of sacrificial beings in the cult pit near the central burial in kurgan 1 at Purcari. This assemblage consisted of remains of a sheep, a horse, cattle and a human, and probably represented the concept of the universe in ritual, natural and social meanings. Both the combination of the objects and the arrangement of sacral offerings had to embody the idea of cosmogonic order as a whole.

Meanwhile, specific combination of prestige things in isolated richest graves, except manifestation of universalism, can probably express another concern of elites related to their exclusivity. Supposedly, only exclusive persons of the highest rank have been allowed to demonstrate ‘universalism’ so conspicuously, and then such materialization of this quality can be conceived as a manifestation of particularism. However, one more way has existed to separate the elites from the masses – sumptuary laws or customs.

Sumptuary laws were the simplest way for a society to set apart the upper social strata. As a rule, they apply to differences in dress, ornamentation, and deportment allowed to privileged people. For example, among the aboriginal population on the northwest coast of Northern America, only heads of lineages were allowed to wear adornments made of abalone shell or to have their robs trimmed with sea-otter fur. Similarly, in the Natchez chiefdom in the Lower Mississippi Basin, only women from the uppermost stratum were permitted to adorn their hair with diadems made of the feathers of swans (Farb, 1968, p. 140, 161). Actually, the same kind of regulations has been practiced in the Usatovo society. For instance, an obvious concentration of ornaments made of rare or exotic materials is observed in kurgan cemetery I at Usatovo (Manzura, 2019, p. 85, Fig. 15). To lesser degree, such ornaments are present in kurgan cemetery II, and they are totally absent in the flat cemetery. At the same time, only kurgan cemetery I has some graves that contain silver hair rings which can be regarded as signs of the highest rank. In kurgan cemetery II at Usatovo, similar hair rings were made of bronze or copper that can testify to a lower rank or status, although occasionally such metal rings are evidenced in the first cemetery too. In other parts of the Usatovo culture area, silver hair rings are also associated with the richest burial sites and with the most prominent graves within these sites. Consequently, this type of ornaments must be considered as unique symbol of social elite accepted throughout the cultural area. It is interesting to note that similar presentations of authority were used in different epochs and cultures of prehistoric Europe (Hansen, 2018, p. 285–288). They were rings of power, indeed. Of course, there were other means to separate elites from the masses, for instance, tattoo designs, color and style of dress, special place in banquets and ceremonial events, but it is impossible to trace these in archaeological record.

As a separate social group, the elites in the Usatovo society have had to be reproduced by means of certain codified rules. Supposedly, the restricted character of the group, probably, has eliminated recruitment of new members from lower strata, so social reproduction could be based on hereditary principles for assignment of corresponding status or occupation of political office. Such practice can be exemplified by children’s burials with attributes of the highest rank. For instance, in the tumulus at Aleksandrovka, a lateral child’s grave, besides lavish and diversified inventory consisted mostly of prestigious items, also contained silver hair rings as a sign of the same status as the central male grave with similar rings (Петренко, Бейлекчи, 2004, p. 390). Inheritance of a status could be also observed in other social groups, especially in privileged ones, as it is documented, for instance, in the Mayaki cemetery (Manzura, 2020, p. 90). Here, some children’s graves were equipped by bronze daggers and whetstones. The same things accompanied graves of adult males which could belong to professional warrior estate whose emergence is recognized in this period (Hansen, 2013, p. 107; Jeunesse, 2017). At the same time, social relations of hereditary character in the Usatovo society seem to have existed in accordance with fundamental social differentiation based on sex and age distinctions, as well as perhaps on property and professional relations.

In order to secure their positions and influence in society, elites had to legitimize their power. There are different ways to do it: sacralization of power, sophisticated propaganda, social manoeuvring, or a combination of all these and other methods. The simplest way lies in sacralization of power and the person of a supreme leader. Of course, in this case, celestial charisma is extended all over members of the ruler’s family. Then, any attempt to oppose the supreme authority had to be considered as a riot against the divine will and the universal order which can bring dangerous consequences for the whole society. Precisely this method of legitimation of power seems to have been realized in the first place in the Usatovo culture. Abundance of sacred symbols in form of various stone steles, stone altars, and engraved mythical scenes and images on slabs, as well as some specific items of grave goods in the first kurgan cemetery at Usatovo allows us to consider persons buried here as sacrosanct leaders with sacerdotal functions.

Despite his divine authority, the supreme leader could realize that his power was not as limitless as the surrounding steppes, so he was forced to court the favor of heads of clans and lineages and look for support of social institutions, first of all, such as priesthood and warriorhood. It can be supposed that priesthood as a separate social institution already could exist at this time, although remains of temples still are not found in the Usatovo cultural area. Nevertheless, the settlement at Usatovo–Bolshoy Kuyalnik near the first kurgan cemetery is interpreted not as a habitation area, but as a sanctuary or a sacred place for different religious ceremonies for a very long period (Petrenko, 2008, p. 32–33). Additionally, complex and sophisticatedly organized burial structures with numerous cult depositions, altars for sacrificial offerings, various anthropomorphic and zoomorphic images testify to complicated religious and cosmogonic ideas and practices as well as developed mythical structure. Such deep and diversified knowledge in rites and rituals and other religious matters seems to have required long-term training which could be implemented within relevant social institution. The priests could represent part of local or regional elites and provide essential support to a ruler who could function as a supreme priest. Similarly, an organized band of professional warriors was able to protect elite’s rights from external and inner infringements, and there are direct and indirect evidence for such military force.

There were other conditions which could favor the legitimation of elites in the Usatovo culture. The society under consideration is distinguished by complex inner structure presented also in economic activities. Economic prosperity of the society was based on semi-mobile stockbreeding in the first place, but other forms of activities were developed too: agriculture, metalworking, carpentry, stone cutting, ceramic production, etc. Successful management, appropriate adoption and encouragement of new technologies, abilities to mobilize all available resources and effectively redistribute them among different groups of population could reduce social tension and raise prestige and authority of central power. Complex character and sufficiently long history of the Usatovo culture demonstrate that these managerial tasks were successfully realized.

3. Conclusion

The Usatovo culture can be undoubtedly regarded as one of the best examples of complexly organized societies in the European Late Eneolithic and the Early Bronze Age. Any neighboring synchronous cultures in the Balkan–Carpathian region (the Cernavodă III and the Boleráz cultures), Central Europe (the Funnel Beaker and the Globular Amphora cultures), and the East-European steppes (the late Lower Mikhaylovka and the Kvityanskaya cultures) do not bear traces of similar level of complexity expressed in variety of burial customs and material evidence. Only the Maykop culture in the highest point of its development in Ciscaucasia and, to some extent, synchronous local groups of the late Tripolye culture in the forest-steppe zone (Brînzeni, Vykhvatintsy, Sofievka) are comparable to the Usatovo culture.5

The ternary structure of Usatovo cemeteries probably should reflect a hierarchical type of social organization consisting of at least three separate strata or classes which can be conditionally termed as the Nobles, the Honoured, and the Commoners. This differentiation perhaps was supplemented by unequal position of individual local communities in common social structure that could be determined by their proximity to the dominant clan or their place in the economic structure. For instance, some graves in the Mayaki and Sadovoe cemeteries contained quite rich inventory, including metal objects and ornaments from rare or exotic materials, but symbols of the highest authority and specific packet of items – “dagger-adze-chisel-awl” – were absent there.

Traces of elites as a separate social group are clearly discernible in necropolises of the highest rank. They had to represent a core within the noble class and possess particular attributes. In this context, the burials discussed above can be considered as eloquent manifestation of such elitist group since they demonstrate by means of material symbols the two most important traits of elite culture – universalism and particularism. These “princely” graves probably belonged to heads of a dominant clan who occupied position of the supreme chief in the society. Only members of this ruling clan seem to have been allowed to wear silver hair rings and other ornaments from this metal as symbols of the highest social status. This rule was applied also to small children who probably had right to inherit the political office.

According to its social nature and organization, the Usatovo society very likely was a theocracy, where both secular and sacerdotal authority was embodied in the sacralized supreme leader. Main administrative positions, such as war chiefs, the most important priests, heads of villages, custodians of public works, envoys, etc. were probably assigned to representatives of the ruling clan. Members of lower stratum who were permitted to wear bronze/copper hair rings, could play roles of priests, professional warriors, assistants of administrative officials, etc. Main social support of supreme power could be based on different social institutions, for example, priesthood and military force, perhaps in the form of warrior clubs or fraternities. They were able to maintain established social order by force of persuasions or coercion depending on concrete situation, as well as protect external borders by diplomatic efforts or armed defence. Traces of numerous traumas on skulls and other bones of male skeletons (Зиньковский, Петренко, 1987, p. 26–31) can evidence that external and inner tension not always could be resolved by peaceful means. Then, in the context of the Usatovo culture, the elite can be considered as a separate kin-based group within a dominant social stratum or class in hierarchically organized society controlling all administrative, religious, and military functions in relevant social institutions, maintaining its legitimacy, privileges, and individuality by means of sacral authority, hereditary rights and sumptuary customs. Due to changing nature of social elites, this definition cannot be applied to all periods of human history, although in later prehistory such traits could have rather universal character.

There was a series of factors which could favor to emergence of complex hierarchical structures with concomitant social elites in the steppe zone close to the middle of the 4th millennium BC. There is a quite convincing indication that in the first half of the millennium, a new type of economy was introduced which was based on the breeding of small livestock and the development of more mobile forms of herding (Манзура, 2017, p. 123). This new specialized and effective form of animal husbandry was able to supply communities with stable surplus which could be accumulated and redistributed by heads of the most successful clans or lineages. Simultaneously, a whole number of important innovations was brought in technological, economic and ideological spheres (Hansen, 2014) which could stimulate further development of economic activities and intensify social differentiation. Additionally, significant experience in social and political organization of complex societies was accumulated in neighboring giant super-centres of the Cucuteni–Tripolye culture which flourished in the forest-steppe belt in the second quarter of the 4th millennium BC. This bundle of prerequisites probably was skilfully and creatively utilized by successful leaders who really succeed in construction of new type of society based on power of elites.

References

Cohen A. 1981. The Politics of Elite Culture: Explorations in the Dramaturgy of Power in a Modern African Society. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Dergačev V. A. 1991. Bestattungskomplexe der späten Tripolje-Kultur. Materialen zur Allgemeinen und Vergleichenden Archäologie 45. Mainz am Rhein: Zabern.

Evers S. 2002. The construction of elite status in the extreme Southern Highlands of Madagascar. C. Shore and S. Nugent (eds.) Elite Cultures: Anthropological Perspectives. London and New York: Routledge, p. 158–172.

Farb P. 1968. Man’s Rise to Civilization as shown by the Indians of North America from Primeval Times to the Coming of the Industrial State. New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., Inc.

Haller D. 2012. Hierarchies and Elites – an Anthropological Approach. T. L. Kienlin and A. Zimmermann (eds.) Beyond Elites: Alternatives to Hierarchical Systems in Modelling Social Formations. Bonn: Habelt, p. 83–89.

Hansen S. 2002.«Überausstattungen» in Gräbern und Horten der Frühbronzezeit. J. Müller (Hrsg.) Vom Endneolithikum zur Frühbronzezeit: Muster sozialen Wandels? Tagung Bamberg 14.–16. Juni 2001. Universitätsforschungen zur prähistorischen Archäologie 90. Bonn: Habelt, p. 151–173.

Hansen S. 2012. The Archaeology of Power. T. Kienlin and A. Zimmermann (eds.) Beyond Elites: Alternatives to Hierarchical Systems in Modelling Social Formations. International Conference at the Ruhr-Universität Bochum, Germany October 22–24, 2009. Bonn: Habelt, p. 213–224.

Hansen S. 2013. The Birth of the Hero. The emergence of a Social Type in the Fourth Millennium BC. E. Starnini (ed.) Unconformist Archaeology. Papers in honour of Paolo Biagi. British Archaeological Reports International Series 2528, p. 101–112.

Hansen S. 2014. The 4th Millennium: A Watershed in European Prehistory. B. Horejs and M. Mehofer (eds.) Western Anatolia before Troy: Proto-Urbanization in the 4th Millennium BC? Proceedings of the International Symposium held at the Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien, Vienna, Austria, 21–24 November, 2012. Vienna: OAW, p. 243–259.

Hansen S. 2018. Elements for an Iconography of Bronze Age Graves in Europe. Ü. Yalçın (ed.) Anatolian Metal VIII. Eliten–Handwerk–Prestigegüter. Bochum: Deutschen Bergbau-Museum Bochum, p. 281–293.

Harding A. 2015. The emergence of elite identities in Bronze Age Europe. Origini, 37, p. 111–121.

Jeunesse Ch. 2017. Emergence of the Ideology of the Warrior in the Western Mediterranean during the Second Half of the Fourth Millennium BC. Eurasia Antiqua, 20, p. 171–184.

Lichter C. 2018. Frühbronzezeitliche Eliten in Anatolien im Licht der Gräber. Ü. Yalçın (ed.) Anatolian Metal VIII. Eliten–Handwerk–Prestigegüter. Bochum: Deutschen Bergbau-Museum Bochum, p. 77–90.

Manzura I. 2020. History Carved by the Dagger: the Society of the Usatovo Culture in the 4th Millennium BC. S. Hansen (Hrsg.) Repräsentationen der Macht. Beiträge des Festkolloquiums zu Ehren des 65. Geburtstags von Blagoje Govedarica. Wiesbaden: Harrasowitz Verlag, p. 73–97.

Marcus G. E. 1983. “Elite” as a Concept, Theory and Research Tradition. G. E. Marcus (ed.) Elites: Ethnographic Issues. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, p. 7–27.

Özdoğan M. 2018. Defining the Presence of an Elite Social Class in Prehistory. Ü. Yalçın (ed.) Anatolian Metal VIII. Eliten–Handwerk–Prestigegüter. Bochum: Deutschen Bergbau-Museum Bochum, p. 29–42.

Petrenko V. 2008. Ancient Trypilians in the Steppe Zone: Usatove sites. C. Krzysztof (ed.) Mysteries of Ancient Ukraine: The Remarkable Trypilian Culture, 5400–2700 BC. Toronto: Royal Ontario Museum, p. 32–44.

Petrenko V., Bejlekchy V. 2006. The Alexandrovka Barrow. The Burial Site of the Usatovo Culture Elite. Pratiques funéraires et manifestations de l’identité culturelle (Âge du Bronze et Âge du Fer). Actes du IVe Colloque Iternational d’Archéologie Funéraire organisé à Tulcea, 22–28 mai 2000, par l’Association d’Études d’Archéologie Funéraire avec le concours l’Institut de Recherches Éco-Muséologiques de Tulcea. Tulcea, p. 259–260.

Rassamakin Yu. 1999. The Eneolithic of the Black Sea Steppe: Dynamics of Cultural and Economic Development 4500–2300 BC. M. Levine, Yu. Rassamakin, A. Kislenko and N. Tatarintseva (eds.) Late prehistoric exploitation of the Eurasian steppe. Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, p. 59–182.

Shore C. 2002. Introduction: towards an anthropology of elites. C. Shore and S. Nugent (eds.) Elite Cultures: Anthropological Perspectives. London and New York: Routledge, p. 1–21.

Wright Mills C. 1956. The Power Elite. New York: Oxford University Press.

Дергачев В. А. 1980. Памятники позднего Триполья (опыт систематизации). Кишинев: Штиинца.

Збенович В. Г. 1974. Позднетрипольские племена Северного Причерноморья. Киев: Наукова думка.

Зиньковский К. В., Петренко В. Г. 1987. Погребения с охрой в усатовских могильниках. Советская археология, № 4, c. 24–39.

Клочко В. И., Козыменко А. В. 2017. Древний металл Украины. Киев: ООО «Издательский дом “САМ”».

Клочко В. І., Козименко А. В., Гошко Т. Ю., Клочко Д. Д. 2020. Епоха раннього металу в Україні (історія металургії та генезис культур). Київ: Національний університет «Києво-Могилянська Академія».

Малюкевич А. Е., Агульников С. М., Попович С. С. 2017. Курганы правобережья Днестровского лимана у c. Молога. Одесса-Кишинев: Одесский археологический музей НАН Украины.

Манзура И. В. 2017. Восточная Европа на заре курганной традиции. Л. Б. Вишняцкий (ред.) Ex Ungue Leonem. Сборник статей к 90-летию Льва Самуиловича Клейна. Санкт-Петербург: Нестор-История, c. 107–129.

Мелюкова А. И. 1962. Курган усатовского типа у с. Тудорово. Краткие сообщения Института археологии АН СССР, 88, c. 74–83.

Патокова Э. Ф. 1979. Усатовское поселение и могильники. Киев: Наукова думка.

Патокова Э. Ф., Петренко В. Г. 1989. Усатовский могильник Маяки. Э. Ф. Патокова, В. Г. Петренко, Н. Б. Бурдо, Л. Ю. (ред.) Полищук, Памятники трипольской культуры в Северо-Западном Причерноморье. Киев: Наукова думка, c. 50–81.

Петренко В. Г. 1989. Усатовская локальная группа. Э. Ф. Патокова, В. Г. Петренко, Н. Б. Бурдо, Л. Ю. Полищук (ред.) Памятники трипольской культуры в Северо-Западном Причерноморье. Киев: Наукова думка, c. 81–124.

Петренко В. Г. 2013a. Металл и усатовская культура. Г. М. Тощев, Я. Б. Михайлов, О. В. Заматаєва, О. В. Пеньова (ред.) Північне Приазов’я в епоху кам’яного віку-енеоліту. Матеріали міжнародної наукової конференції присвяченой до 100-річчя від дня народження В.М. Даниленка. Мелітополь: Мирне, c. 146–153.

Петренко В. Г. 2013b. Усатовская культура. И. В. Бруяко, Т. Л. Самойлова (ред.) Древние культуры Северо-Западного Причерноморья. Одесса: Одесский археологический музей, c. 163–210.

Петренко В. Г., Алексеева И. Л. 1994. Могильник усатовской культуры у с. Ясски в Нижнем Поднестровье. С. Б. Охотников (ред.) Древнее Причерноморье. Краткие сообщения Одесского археологического общества. Одесса, c. 48–55.

Петренко В. Г., Сапожников И. В., Сапожникова Г. В. 1994. Геометрические микролиты усатовской культуры. С. Б. Охотников (ред.) Древнее Причерноморье. Краткие сообщения Одесского археологического общества. Одесса, c. 42–47.

Петренко В. Г., Бейлекчи В. В. 2004. Олександрівский курган. С. М. Ляшко, Н. Б. Бурдо, М. Ю. Відейко (ред.) Енциклопедія Трипільської цивілізації. Т. 2. Київ: Укрполіграфмедіа, c. 389–390.

Черняков И. Т. 1963. Итоги полевых исследований 1961 года Одесского археологического музея. Краткие сообщения о полевых археологических исследованиях Одесского государственного археологического музея 1961 года, c. 3–7.

Черняков І. Т. 2004. Аккембецький курган. С. М. Ляшко, Н. Б. Бурдо, М. Ю. Відейко (ред.) Енциклопедія Трипільської цивілізації. Т. 2. Київ: Укрполіграфмедіа, c. 11–13.

Яровой Е. В. 1990. Курганы энеолита-эпохи бронзы Нижнего Поднестровья. Кишинев: Штиинца.

1 I am sincerely grateful to Denis Topal for his friendly assistance in correlation procedure and construction of the graph.

2 It has been by mistake indicated on the graph (Fig. 15) in Manzura (2020) that one grave at the Second kurgan cemetery at Usatovo contained a necklace of red deer teeth. In fact, the necklace was composed of canine teeth, and ornaments of deer teeth here are not evidenced.

3 In material for a field report on excavation at Aleksandrovka, V. Petrenko mentions several small barrows around the biggest one which can constitute a common cemetery of the Usatovo culture. Unfortunately, the field report itself is absent in archives of the Odessa Archaeological Museum and Institute of Archaeology in Kiev.

4 Remains of the third kurgan cemetery have been uncovered on the eastern edge of the Usatovo village, however all tumuli were completely destroyed by modern structures. Some anthropomorphic and zoomorphic steles derive from this area, see: Черняков, 1963, p. 4.

5 Recently published data demonstrate a high level of metalworking in the area of the late Tripolye culture, including production of such weapons as shafted axes, daggers and swords – see: Клочко, Козыменко, 2017; Клочко et al., 2020.