Respectus Philologicus eISSN 2335-2388

2025, no. 47 (52), pp. 66–80 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15388/RESPECTUS.2025.47.5

The Progressive: a cross-linguistic study of English and Albanian

Libron Kelmendi

University of Prishtina “Hasan Prishtina”, Faculty of Philology

31 George Bush St, 10000 Prishtinë, Republic of Kosovo

Email: libron.kelmendi@unhz.eu

ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6298-7953

Research interests: Linguistics, Communication, Language teaching

Sadije Rexhepi

University of Prishtina “Hasan Prishtina”, Faculty of Philology

31 George Bush St, 10000 Prishtinë, Republic of Kosovo

Email: sadije.rexhepi@uni-pre.edu

ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0478-7560

Research interests: Linguistics, Communication, Language teaching

Abstract. This study explores the use and distribution of progressive forms in English and Albanian. The English-Albanian analysis is significant as it examines how two linguistic systems organize and encode the progressive aspect, revealing the structural contrasts that define their grammatical frameworks. The theoretical part outlines English and Albanian progressive forms. The research analyses English progressive forms translated into Albanian and Albanian progressive forms translated into English. The paper focuses on the progressive be+verb-ing of English. Research shows that, of the two Albanian progressive forms, the po participle (despite being limited to the present and imperfect) is more common and frequently used than the jam+duke+participle structure. There is a difference in how progressive forms are translated between English and Albanian. While 50% of Albanian po forms correspond to English progressives, 58% of English progressives are translated into Albanian using po, reflecting a nuanced difference in their usage across the languages. In conclusion, this shows that the status of the English progressive aspect differs from that of the Albanian progressive.

Keywords: English language; Albanian language; aspect; progressive aspect; progressive forms.

Submitted 30 October 2024/ Accepted 23 January 2025

Įteikta 2024 10 30 / Priimta 2025 01 23

Copyright © 2025 Libron Kelmendi, Sadije Rexhepi. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License CC BY 4.0, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

This study examines the progressive aspect – a subtype of the imperfective aspect – focusing on its forms and usage in English and Albanian. It comprises three sections: a theoretical review of the progressive aspect in English and Albanian, an empirical analysis of translations between the two languages, and a discussion of findings in relation to linguistic theories. The study aims to contribute to the growing body of research on linguistic aspects and cross-linguistic studies by focusing on these elements.

Cross-linguistic studies, such as this, enhance our understanding of individual languages while contributing to broader debates, including cognitive versus structuralist approaches to grammatical categories. Cognitive linguists argue that grammatical forms reflect conceptualisations of time and event structures, while structuralist perspectives emphasise such categories’ systematic, language-specific realisations. This study bridges these perspectives by comparing English and Albanian, offering a nuanced view of how progressiveness is expressed.

The significance of the English-Albanian comparison lies in the typological differences between the two languages. English has a highly grammaticalised progressive aspect, while in Albanian, progressiveness is expressed through more lexically driven means, such as the particle po and the analytical construction jam+duke+participle. Understanding these contrasts illuminates the broader spectrum of aspectual representation in human language. Linguistic debates, such as the cognitive versus structuralist approach, focus on differing perspectives regarding how languages are structured and how humans process language. The cognitive approach posits that grammatical structures, including categories like aspect and tense, reflect innate mental processes and conceptualisations. It emphasises how language encodes the speaker’s view of events and temporal relations, as seen in Bernard Comrie’s (1976, 1985) studies on aspect. In contrast, the structuralist approach focuses on the systematic, language-specific rules that govern linguistic categories. Structuralists examine how grammatical features, like progressive aspect in English and Albanian, are embedded in language systems as formal, rule-governed constructs independent of universal cognitive processes.

These debates become particularly intriguing in cross-linguistic studies, such as this comparison of English and Albanian progressiveness. With its highly grammaticalised progressive forms, English demonstrates a cognitive view of action as a dynamic process. Albanian, however, relies on lexical markers like po and jam+duke, which are less grammaticalised and context-dependent, aligning more with structuralist interpretations of linguistic variance. Such studies bridge these paradigms by showcasing how structural differences can illuminate cognitive universals, underscoring the interplay between mental processes and language-specific realisations.

1. Research questions

The cross-linguistic study of the progressive forms in English and Albanian aims to identify the differences and similarities between the progressive forms in both languages. To achieve this aim, the present study addresses the following questions:

1. How are the progressive forms of English translated into Albanian? Do they match the progressive forms in Albanian?

2. In the translation of progressive forms from English to Albanian, does the structure using the participle po prevail over the jam+duke+participle structure?

3. How are the progressive forms that use the participle po in Albanian translated into English? Do they correspond to the progressive forms of English?

4. How do the structures of progressive forms and the use of these forms differ in the two languages?

By addressing such research question, the study seeks to:

1. Analyse how English progressive forms are translated into Albanian and whether they match Albanian progressive forms.

2. Investigate the dominance of the participle po versus the jam+duke+participle structure in Albanian translations of English progressives.

3. Examine how Albanian progressive forms (po and jam+duke) are translated into English and assess their correspondence to English progressives.

4. Identify broader structural and functional differences in the usage of progressive forms between the two languages.

2. Methodology

This study employs a contrastive and descriptive methodology, combining qualitative and quantitative approaches. As part of the qualitative research, a detailed review was conducted to categorise progressive forms (e.g., po+verb, jam+duke+participle) and examine their contextual usage. This includes analysis of academic studies, articles, and books concerning progressive forms in both languages. The quantitative research focused on analysing the frequency and distribution of progressive forms, focusing on their translation patterns and structural variations. Quantitative research was based on the analysis of the selected corpus, which consists of a text published in the original English language, that of William Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury (1995) and its translation into Albanian by Abdullah Karjagdiu Këlthitja and mllefi (2005) and from a text published in Albanian, Ismail Kadare’s Prilli i Thyer (1980) translated into English as Broken April by John Hodgson, New Amsterdam Books. Both texts are representative of their respective linguistic and cultural contexts. Faulkner’s work is a cornerstone of modernist literature in English, showcasing typical yet sophisticated uses of progressive forms. His work represents modernist literature while demonstrating the systematic and nuanced use of progressive forms in English, making it an ideal resource for studying grammaticalisation and aspectual usage. Kadare’s work, on the other hand, is a hallmark of Albanian literature, illustrating common and unique aspect of Albanian grammar in practice. This novel reflects standard and colloquial Albanian usage, providing a comprehensive view of how progressive forms function within Albanian’s broader linguistic and cultural context. Together, these texts bridge literary and linguistic analysis. These texts are particularly suited to the study’s aim of identifying how progressive forms are used and translated. Their rich verb structures and varied contexts ensure a comprehensive analysis of aspects, effectively addressing the study’s research questions.

100 progressive forms were extracted from each text, creating a dataset of 400 instances for analysis. The texts were manually read, and progressive forms were identified as they appeared. The focus was on the first 100 occurrences of progressive forms encountered in each text. Through an empirical study of two texts in their original and translated versions, we analyse data on the distribution, structure, and use of progressive forms in the two languages. Particular attention was given to the equivalency of progressive forms in translation, including cases where the progressiveness was not maintained. Contextual factors influencing translation choices, such as stylistic conventions and grammatical constraints, were also considered. The sample size, while limited, provides specific insights into the linguistic phenomena under study. Future research with larger datasets could further validate these findings.

3. Literature review

3.1 Understanding the grammatical category of aspect

This section explores the grammatical category of aspect. Binnick (1991) notes that “aspect” is derived from the Russian “vid,” related to sight and vision, similar to the Latin root “-spect-” (e.g., perspective, inspection). While tense is familiar in Western European linguistics, the aspect is less traditional and less understood by most European language speakers.

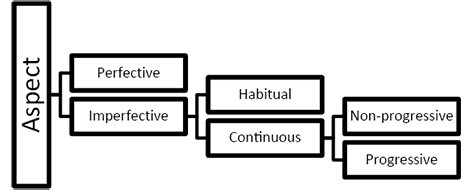

As described by Jakobson (1984) as a deictic category, Tense links events to the act of speaking, whereas aspect, as Dahl (1987) notes, characterises events independently. Comrie (1976) defines aspect as focusing on a situation’s internal temporal structure, unlike tense, which concerns external timing. He also observes that languages vary in their treatment of the imperfective, with some having one form and others multiple subtypes, forming the basis of his aspect classification. Based on this, Comrie (1976) makes a classification of aspects as follows:

Fig. 1. Classification of aspect according to Bernard Comrie (1976)

3.2 The progressive in english

Binnick (1991) notes that the term “aspect,” introduced into English in 1853, originated from Slavic grammar studies and became integrated into Western grammar by the late 19th century. Huddleston and Pullum (2002) define aspect as relating to the internal temporal structure of a situation, distinguishing between non-progressive (external view, no internal flow) and progressive (internal view, ongoing action).

Examples:

Non-progressive: She goes to school (Alb. Ajo shkon në shkollë).

Progressive: She is going to school (Alb. Ajo po shkon në shkollë).

Greenbaum (1996) identifies two aspects in English: perfective, marked by have + verb (-ed), for completed actions (e.g., Has called, Alb. Ka thirrur), and progressive, marked by be + verb (-ing), for ongoing actions (e.g., Is calling, Alb. Po thërret).

Compared to other languages, English progressive forms have broader uses, often linked to action type and verb semantics (Leech, 2004). Progressives generally indicate temporary, ongoing, or incomplete actions and can appear with present, past, or future tenses (Comrie, 1985).

3.3 The progressive in Albanian

The Albanian language offers diverse forms for expressing temporal relationships, though the distinction between tense and aspect remains underexplored. Studies on aspect could enhance understanding of the Albanian verb and tense systems.

Boissin (1998) identified two forms resembling English progressives:

a) Using the particle po (e.g., po punoj, “I am working”).

b) b) Using jam (to be) + duke + present participle (e.g., jam duke punuar, “I am working”).

Demiraj (1964) describes the latter as an analytical structure formed with jam + duke + participle. Buchholz and Fiedler (1987) classify three structures expressing actionality or aspectuality, notably those with po and jam duke. These cannot combine, forming two distinct grammatical forms.

Rugova (2015) highlights aspect as a distinct grammatical category that gained recognition after 2000, linking it to speaker stance and subjectivity. Fridman’s contributions helped distinguish aspect from earlier treatments in Albanian grammar.

Dhrimo (1996) categorised aspect into two main types, noting similarities with European traditions while acknowledging differences with Slavic languages. He emphasised analytical forms for aspectual pairs.

Gurra (2014) compared English and Albanian progressives, stating that both languages share grammatical categories such as person, mood, and aspect. She defines aspect as expressing actions in relation to time, distinguishing continuous and non-continuous forms.

Rugova (2015) further connects aspect with textual categories, voice, focus, and speaker presentation. She advocates for pragmatic analysis to clarify telicity and the nuanced meanings of aspectual forms, emphasising its role in communication and subjectivity.

The following sections will discuss the two progressive forms.

3.1.1 The “po” particle

In modern Albanian, the role of po as a progressive marker is debated, with its terminology still unclear. Agalliu (1982) describes po as a particle, while Newmark (1957) calls it a “prefix,” though this is inaccurate as po is a separate word. Boissin (1998) sees po as a supplementary progressive form influenced by English. Agalliu (1968) argues that po localises actions temporally but later (1982) suggests that its connection to aspect is unnecessary since Albanian’s present and imperfect inherently convey continuity.

Kole (1969) classifies po as an aspectual particle emphasising progressiveness, a view echoed by Demiraj (1964), who highlights its role in expressing ongoing, incomplete actions. He adds that the analytical form jam + duke + participle can also convey this progressiveness. Joseph (2011) notes that po uniquely marks progressive aspect in both main Albanian dialects (Toskë and Gegë).

Buchholz and Fiedler (1987) associate po with expressing simultaneity and “fixation” –the commitment to a specific time point – while observing its limited use with state verbs in literary Albanian. Matasovic (2024) describes po as a progressive marker similar to English, noting its identical form to the adverb po and its use before the present tense (po punoj, “I am working”).

3.1.2 The “duke” particle

According to Demiraj (1964), the particle duke has two main uses in Albanian:

1. Progressive Form: The structure jam + duke + participle can replace the po + verb progressive form (e.g., ishim duke punuar – po punonim; “we were working”). This structure works across all tenses of jam.

2. Gerund-like Function: Without jam, duke functions like the Latin gerundium, indicating a dependent action or state (e.g., duke sjellë – sjell; “bringing” – “brings,” duke pasë sjellë – ka sjellë; “having brought” – “has brought”).

Hysa (1975) also highlights jam + duke as a progressive form, often substituting po + verb. However, this structure is less common in literary language and is more widely used in dialects, where non-standardised variations also appear.

3.1.3 The difference between “po” and “duke”

This section outlines the differences between the Albanian periphrastic structures po and duke. Newmark (1979) identifies two progressive forms:

Progressive with duke: Combines the particle duke with a form of jam (to be) + participle (jam duke shkuar, isha duke shkuar; “I am going,” “I was going”).

Progressive with po: Places po before the verb in the present or imperfect tense (po shkoj, po hap; “I am going,” “I am opening”).

Both forms express ongoing actions, but duke supports more tense combinations (e.g., aorist, subjunctive) and can express assumptions in the future (Ai do të jetë duke udhëtuar; “He will probably be travelling”). According to Buchholz & Fiedler (1987), duke can often replace po, but not always vice versa.

Makartsev (2020) notes that po emphasises foreground actions and applies to both action and state verbs, reflecting the continuous aspect. In contrast, duke highlights background actions and is rarely used with state verbs, reflecting the progressive aspect.

The differences are summarised in the table below.

Table 1. Usage of the participle po and duke as markers of progressivity

|

Particle |

po |

duke |

|

Usage |

“momentary action in progress” (Newmark et al., 1982, p. 36). |

“action already in progress” (Newmark et al., 1982, p. 36). |

|

Forms |

po + verb in present or imperfect |

Jam + duke + participle |

|

I am running. |

I am running. |

|

|

I was running. |

I was running. |

|

|

/ |

I have been running. (Alb. Kam qenë duke vrapuar.) |

|

|

/ |

I had been running. (Alb. Kisha qenë duke vrapuar.) |

4. Results and discussion

The research analysed William Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury (Këlthitja dhe mllefi) and Ismail Kadare’s Prilli i thyer (Broken April). In Faulkner’s translation, 100 progressive forms using be (Alb: jam) + -ing were identified, with 58% rendered in Albanian using po or jam + duke.

In Kadare’s original text, 100 progressive forms were found, with 94 using po and only 6 using jam + duke. This highlights po as the dominant progressive marker in Albanian, while jam + duke is less common.

4.1 Progressive forms in English and their translation in Albanian

This part of the study examined whether English progressive forms are translated as progressive forms in Albanian and whether po dominates over jam + duke in these translations. Among 100 samples, 58 were rendered as Albanian progressive forms, with po overwhelmingly used, while jam + duke was absent.

The English-Albanian analysis showed that 58% of English progressive forms were translated using po + verb, while 42% were translated without po or jam + duke. Thus, po dominates, and jam+duke is not used in the translations.

Table 2. Translation of progressive forms of English in Albanian

|

“The Sound and the Fury” |

“Këlthitja and Mllefi” |

% |

|

|

Verb form with the auxiliary verb jam (be) + V-ing |

Structure with the participle po |

58 |

58% |

|

100 |

Jam+duke structure |

0 |

0% |

|

Simple aspect without the participle po or jam+duke |

42 |

42% |

|

|

Total: |

100 |

100% |

|

English progressives translated into Albanian without the particle po fall into two categories: those excluded due to lexical meaning (e.g., the present tense indicating a habitual action) and those where po is not used with aorist forms or in the passive voice (as shown in Table 3, B. 2e). In these cases, English progressives are rendered using the Albanian present or imperfect tense. However, testing 42 Albanian samples without po or jam + duke showed that most could accommodate po in literal translations.

Overall, the analysis confirms that po is compatible with the present and imperfect tenses, while Albanian progressiveness is less grammaticalised and more context-dependent than in English.

The table below provides examples of English progressives translated with and without progressive forms in Albanian.

Table 3. Samples from the English-Albanian research

|

A. Progressives in English from |

B. Translation in Albanian from |

||

|

1a. Caddy was walking. 1b. That’s where they are killing the pig. 1c. Luster was playing in the dirt. 1d. We’re going to the cemetery. 1e. They were going up the hill ... |

2a. “I’m coming.” 2b. Dilsey was moaning. 2c. Then she was running, ... 2d. We’re going out doors again. 2e. She was trying to climb the fence. |

1a. Po vinte Kedi. 1b. Ja, atje po thernin një derr. 1c. Llaster po luante në baltë. 1d. Po shkojmë në varreza. 1e. Ata po i qepeshin kodrës ... |

2a. “Erdha.” 2b. Qante edhe Dilzi. 2c. ..., ia dha vrapit. 2d. Të dalim përsëri. 2e. U mundua ta kapërcente gardhin. |

The examples given, from 1a to 1e in column A, are progressive forms in the original English text, which were translated into Albanian progressives with the particle po, and their equivalent is shown in column B. The progressive form is translated with the particle po to emphasise the continuous nature of the action. For example:

1a. “Caddy was walking” is translated as “Po vinte Kedi.”

1c. “Luster was playing in the dirt” is translated as “Llaster po luante në baltë.”

In these translations, the particle po is key to indicating progressiveness in Albanian. This shows a clear correspondence between the progressive forms in both languages.

The examples given in column A (2a to 2e) are progressive forms identified in the original English text that were not translated as progressive forms with the particles po or jam+duke in Albanian. Their translation is provided in column B. For instance:

2a. “I’m coming” is translated as “Erdha,” without using the particle po.

Here, the verb comes in the past simple tense (erdha). The past simple can be used with a future meaning when the speaker presents an action that has not yet started, is expected to occur immediately, or is in progress. This applies to verbs of motion, e.g., Erdha!

2c. “Then she was running” is translated as “..., ia dha vrapit,” an expression that conveys swift action but not progressiveness in Albanian.

In these cases, the translator chose to convey the meaning of the action, but not necessarily its progressiveness, using forms that better convey the idea of the action in the context in Albanian.

Below is a more detailed analysis of some examples from the corpus that were not translated into progressive Albanian forms. These examples reflect the translator’s stylistic and structural choices based on the context and the target language. Under a), we have the original from the English text, and under b), we have the translated form in Albanian.

a) “They were coming toward where the flag was and I went along the fence.”

b) “Derisa ata zunë t’i qaseshin flamurit, unë fillova t’i përcjell duke ecur pas gardhit.”

In this example, the translator chose to use a structure that indicates the beginning of an action (“zunë t’i qaseshin”) and another continuous action (“t’i përcjell”). Instead of using the progressive form “po vinin,” the translator chose a form that, through the lexical aspect of the verb zunë, indicates the initiation of an action, making the translation more dynamic and suitable for the Albanian context.

a) “Luster was hunting in the grass by the flower tree.”

b) “Llesteri kërkonte diçka në bar, afër pemës që kishte çelur behar.”

Here, the progressive form “was hunting” is translated with the verb “kërkonte.” In this case, the translator chose the synthetic form of the imperfect tense (“kërkonte”) to maintain the simultaneity of actions, fluidity, and naturalness in Albanian, thus avoiding the use of the progressive form “po kërkonte.”

a) “Quentin was still standing there by the branch.”

b) “Kuentini ende ndodhej pranë përroskës.”

In the original, “was still standing” indicates a continuous action in the past. The Albanian translation “ndodhej” is a non-progressive form. In this case, progressiveness is expressed through the adverb “ende” (still). This change may have been made to maintain naturalness in Albanian and to avoid a more complex structure such as “ishte duke qëndruar.”

a) “The roof was falling.”

b) “Çatia desh kishte renë.”

In this case, the translator chose an imperfect form “desh kishte renë,” where the word “desh” means “almost” or “about to” indicating something in progress or focusing on the action before the described event occurred, conveyed by the verb in the pluperfect tense “kishte renë.” This avoids the progressive form and uses a structure more natural and common in Albanian to describe such a situation.

a) “While I was eating, I heard a clock strike the hour.”

b) “Gjatë ngrënies veshi ma zuri tiktakun e orës.”

“Was eating” is not translated as a progressive form but as the phrase “gjatë ngrënies” (during the meal). In Albanian, adverbs are often preferred to describe prolonged actions, thus avoiding the progressive form as a formal marker. This translation maintains a simple and concise style, avoiding a longer form like “Derisa isha duke ngrënë.”

In general, the analysis of the examples shows that translators take a flexible approach to progressive forms, considering context and style in Albanian. In some cases, the progressive form emphasises the continuous action, while in others, the translators choose simpler lexical forms for Albanian to avoid complexity and preserve the flow of the text.

4.2 Progressive forms in Albanian and their translation in English

The structures with the particle po and the jam+duke structures were examined based on the verb aspect in which they appeared. In this part of the study, 100 samples were identified from the novel “Prilli i thyer”, with 94 using the particle po and 6 using the jam+duke structure. Regarding the tenses used with the progressive particle po, the largest distribution was between po+present tense (16%) and po+imperfect tense (78%). The remaining percentage (6%) corresponds to the progressive forms in jam+duke structure.

Table 4. Translation of progressive forms of Albanian in English

|

“Prilli i thyer” |

“Broken April” |

% |

||

|

Verb form with the participle po |

94 (94%) |

Progressive aspect |

50 |

50% |

|

Simple aspect |

44 |

44% |

||

|

Verb form with jam+duke |

6 (6%) |

Progressive aspect |

6 |

6% |

|

Total: |

100 |

100% |

||

This part of the study aimed to determine whether Albanian progressive forms with the particle po are translated as progressive forms in English. The analysis revealed a predominant equivalence, with po structures matching English progressives in more than half of the cases.

The table below illustrates examples where po forms were translated as progressives in English and instances where they were not.

Table 5. Samples from the Albanian-English research

|

A. Progressives in Albanian |

B. Translation in English |

||

|

1a. Dita po thyhej. 1b. Kryesorja ishte ajo që po ndodhte brenda tij. 1c. Ika, zotni, po ma bën me shenjë Ali Binaku, ustai Im. 1d. Ja, kulla e të vrarit po afrohej. 1e. Gjaku po zverdhet në të, – tha i ati. |

2a. Ai e ndjeu që po skuqej... 2b. Askush nuk po fliste. 2c. Po shkojmë pas kuajve të tyre, — tha Besiani 2d. Përballë tij po vinte një grup i vogël malësoresh... 2e. I gëzuar që ajo po gjallërohej, ai i shtrëngoi krahun . |

1a. Daylight was fading. 1b. What was happening within him was the important thing. 1c. I’m going off now, sir. Ali Binak, my master, is beckoning me. 1d. They were coming close to the house of the dead man. 1e. “The blood is turning yellow,” his father said. |

2a. He blushed... 2b. No one spoke. 2c. “We’ll follow their horses,” Bessian said. 2d. He met a small party of mountaineers... 2e. Happy to see her a little more cheerful, he pressed her arm. |

Above, we have presented some samples identified in the novel “Broken April.” The examples given 1a to 1e in column A are progressive forms identified in the original Albanian text. These forms have been translated into English as progressive forms, and their equivalent translations are shown in column B. For example:

1a. “Dita po thyhej” is translated as “Daylight was fading.”

1d. “Ja, kulla e të vrarit po afrohej” is translated as “They were coming close to the house of the dead man.”

Here, an explicit correspondence is seen between the progressive form in Albanian and in English, where po+verb in Albanian corresponds to the be+verb+-ing structure in English. This indicates that when progressiveness is essential to the context, both languages use similar forms to express an ongoing action.

In contrast, the examples given in columns A, 2a to 2e are progressive forms identified in the original Albanian text that have not been translated as progressive forms in English. Their translations are shown in column B. For example:

2a. “Ai e ndjeu që po skuqej” is translated as “He blushed...,” avoiding the progressive structure.

2b. “Askush nuk po fliste” is translated as “No one spoke,” without using the progressive form in English.

The English translation is without progressive forms in these cases, as the context does not necessarily require this. In some cases, the translation favours a simple form (e.g., “He blushed” instead of “He was blushing”) to maintain the naturalness of expression.

Below, we have a more detailed analysis of some examples from the corpus that were not translated as progressive forms in English. For each example provided under a) we have the original text in Albanian, and under b) we have the translated form in English.

a) “Përballë tij po vinte një grup i vogël malësoresh...”

b) “He met a small party of mountaineers...”

In the original Albanian, the form “po vinte” indicates a progressive action in progress. However, the English translation does not retain this progressive form and uses the simple structure “He met” focusing solely on the outcome of the action as complete and perfective, omitting the ongoing process of the mountaineers’ arrival. This translation choice was likely made to emphasise the moment of the encounter as a more significant event. In this way, the translator avoided the progressive form and centred the narrative on the result of the action.

a) “Askush nuk po fliste.”

b) “No one spoke.”

In Albanian, the progressive form “nuk po fliste” clearly indicates an action in progress or, in this case, one that was not happening, giving a sense of an ongoing process of silence. In the English translation, the simple form “No one spoke” was used, which eliminates the sense of progressiveness and translates it as a completed action, suggesting that at that moment, no one spoke.

a) “Po afrohemi,” tha Besiani.

b) “We’re nearby,” he said.

In this case, the progressive form in Albanian “po afrohemi” indicates an action currently in progress. The translation into English, “We’re nearby”, implies that the action of approaching is almost complete, even though it does not use an explicit progressive form.

a) “...dhe ai gati po mësohej me idenë se jeta e tij ishte ndarë në dy copa.”

b) “... and already he was almost used to the idea that his life had been cleft in two.”

The progressive form “po mësohej” expresses an ongoing process. In English, «was almost used to» is used to emphasise continuity in adaptation.

a) “Pa i hequr sytë nga ajo copë e pamjes që po mjegullohej përjashta...”

b) “Without taking his eyes off the bit of misty landscape...”

In this example, “po mjegullohej” expresses an action in progress. In English, the adjective “misty” is used to convey a sense of the evolving landscape without using progressive forms.

This study reflects global typological trends in grammaticalisation. English’s dominance of grammaticalised progressiveness aligns with other Indo-European languages like German and Spanish, while Albanian’s context-dependent, periphrastic forms resemble those in Turkish or Hindi. The findings highlight how grammar, context, and translation interact, showcasing cross-linguistic variation and the creative nature of translation. The frequent use of po in English-to-Albanian translations and the adaptations in reverse illustrate the translator’s challenge of balancing semantic accuracy with naturalness in the target language.

5. Limitations and implications

The analysis of 400 progressive forms provides insights but is limited in scope. The chosen texts, reflecting modernist English and Albanian literary traditions, reveal key typological differences: English has a highly grammaticalised system for progressiveness. At the same time, Albanian relies on lexical and context-dependent markers, with po as the dominant form. Future studies with larger, diverse corpora could confirm and expand these findings, contributing to understanding grammaticalisation and cross-linguistic variation in the encoding aspect.

Conclusion

This research confirms that English and Albanian use progressive forms, though their nature and usage differ significantly. English employs a fully grammaticalised, systematic, progressive aspect, while Albanian relies on less formalised structures, with po dominating and jam + duke playing a secondary role. These differences reflect distinct approaches to encoding progressiveness and varying levels of grammaticalisation within their aspect systems.

Translation between the two languages highlights these contrasts. Po was used in 58% of cases when translating from English to Albanian, demonstrating its naturalness. In comparison, 42% of English progressive forms were rendered using non-progressive forms, reflecting the flexibility needed to align with Albanian stylistic norms. Although rare in Albanian, jam + duke structures, when used, are translated directly into English progressives, showing alignment in those cases.

From a translation theory perspective, these findings underscore the challenges of maintaining semantic equivalence across typologically different languages. Translators often compromise, using simpler aspectual forms, adverbs, or lexical strategies to adapt English’s grammaticalised progressiveness to Albanian’s more situational framework. Cognitive linguistics insights further reveal how English’s systematic progressiveness reflects a dynamic conceptualisation of actions, while Albanian’s reliance on po and jam + duke reflects a more context-dependent approach.

The study also has implications for language teaching. Albanian speakers learning English need explicit instruction on the frequent and systematic use of progressives. English speakers learning Albanian should focus on contextual and lexical strategies that replace grammaticalised progressiveness. Understanding these differences can improve teaching methodologies and learner outcomes.

In conclusion, the study highlights the interplay between grammar, translation practices, and cognitive processes. English’s systematic progressive forms contrast with Albanian’s more flexible use of po and other mechanisms, reflecting broader grammaticalisation patterns and cross-linguistic variation. Future research could expand on these findings with larger datasets or explore computational linguistics applications for automated translation systems.

Sources

Faulkner, W., 1995. The Sound and the Fury. London, England: Vintage Classics.

Faulkner, W., 2005. Këlthitja dhe Mllefi [The Call and the Mllefi]. Translated by A. Karjagdiu. Italy: Random House, Inc. [In Albanian].

Kadare, I., 1980. Prilli i Thyer. Tiranë: Rilindja.

Kadare, I., 1990. Broken April. Translated by J. Hodgson. New Amsterdam Books.

References

Agalliu, F., 1968. Vëzhgime mbi kuptimet e disa trajtave kohore [Observations on the Meanings of Some Tense Forms]. In: Studime Filologjike, 2. Tiranë: Akademia e Shkencave, pp. 129–136. [In Albanian].

Agalliu, F., 1982. Mbi pjesëzën po në gjuhën shqipe [On the Particle po in the Albanian Language]. In: Studime Filologjike, 2, pp. 129–136. Tiranë: Akademia e Shkencave. [In Albanian].

Agalliu, F., Angoni, E., Demiraj, Sh., Dhrimo, A., Hysa, E., Lafe, E., Likaj, E., 2002. Gramatikë e gjuhës shqipe, Vëll. I: Morfologjia [Grammar of the Albanian Language, vol. I: Morphology]. Tiranë: Akademia e Shkencave e Republikës së Shqipërisë, Instituti i Gjuhësisë dhe i Letërsisë. [In Albanian].

Boissin, H., 1998. Grammaire de l’albanais moderne. [Grammar of Modern Albanian]. Paris. [In French].

Binnick, R. I., 1991. Time and the Verb: A Guide to Tense and Aspect. New York: Oxford University Press.

Buchholz, O., Fiedler, W., 1987. Albanische Grammatik. Leipzig: Enzyklopädie. [In German].

Comrie, B., 1976. Aspect, an Introduction to the Study of Verbal Aspect and Related Problems. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Comrie, B., 1985. Tense. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dahl, O., 1987. Tense and Aspect Systems. Oxford: Blackwell.

Demiraj, Sh., 1964. Gramatika e gjuhës shqipe [Grammar of the Albanian Language]. Tiranë: Drejtoria e Botimeve Shkollore. [In Albanian].

Dhrimo, A., 1996. Aspekti dhe mënyrat e veprimit të foljes në gjuhën shqipe [The Aspect and Moods of Verbs in the Albanian Language]. Tiranë: Shtëpia Botuese Libri Universitar. [In Albanian].

Greenbaum, S., 1996. The Oxford English grammar. London: Oxford University Press.

Gurra, H., 2014. The Similarities and Differences between English and Albanian Progressive Tenses In Terms of Manner Form Usage Aspect and Modality [WWW Document]. Available at: <https://www.richtmann.org/journal/index.php/jesr/article/view/3485> [Accessed 11 October 2024].

Hysa, E., 1975. Rreth përdorimeve të së pakryerës së dëftores në gjuhën shqipe. [On the Uses of the Imperfect Indicative in the Albanian Language]. In: Studime Filologjike, 3/1975. pp. 101–109. Tiranë: Akademia e Shkencave. [In Albanian].

Huddleston, R. D., Pullum, G. K., 2002. The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jakobson, R., 1984. Shifters, Verbal Categories, and the Russian Verb. Cambridge, Mass. Harvard University Press.

Joseph, B. D., 2011. The Puzzle of Albanian po. In: Ed. Eirik Welo. Indo-European Syntax and Pragmatics: Contrastive Approaches, Oslo Studies in Language, 3(3), pp. 27–40. https://doi.org/10.5617/osla.36. Available at: <https://journals.uio.no/osla/article/view/36/213> [Accessed 19 October 2024].

Kole, J., 1969. Pjesëzat si kategori leksiko-gramatikore në shqipen e sotme [Particles as Lexico-Grammatical Categories in Modern Albanian]. In: Studime Filologjike, 3/1969. pp. 75–108. Tiranë: Akademia e Shkencave. [In Albanian].

Leech, G., 2004. Meaning and the English Verb. London: Longman.

Makartsev, M., 2020. Grammaticalisation of Progressive Aspect in a Slavic Dialect in Albania. Journal of Language Contact, 13, pp. 428–458. https://doi.org/10.1163/19552629-bja10012. Available at: <https://brill.com/view/journals/jlc/13/2/article-p428_428.xml> [Accessed 22 December 2024].

Newmark, L. Prifti, P., Hubbard, P., 1979. Readings in Albanian. Part 1. Spoken Language Services, Inc., Ithaca, NY. Available at: <https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED195133.pdf> [Accessed 27 September 2024].

Newmark, L., 1957. Structural Grammar of Albanian. (International Journal of American Linguistics, 23.4.). Bloomington: Indiana University.

Rugova, L., 2015. Kundërvëniet aspektore brenda shqipes në studimet e Friedman-it dhe në studimet e sotme të shqipes [Aspectual Oppositions within Albanian in Friedman’s Studies and Contemporary Albanian Studies]. In: Studimet Albanistike në Amerikë. Prishtinë: ASHAK, pp. 235–253. [In Albanian].

Author contributions

Libron Kelmendi: conceptualisation, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, writing – original draft.

Sadije Rexhepi: supervision, conceptualisation, investigation, writing – review and editing, project administration.