Social Welfare: Interdisciplinary Approach eISSN 2424-3876

2022, vol. 12, pp. 36–55 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/SW.2022.12.13

Piloting a Strengths-Based Intervention to Enhance the Quality of Life of Families Raising Children With Autism

Olha Stoliaryk (Corresponding Author)

Ivan Franko National University of Lviv, Ukraine

olgastolarik4@gmail.com

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1105-2861

Tetyana Semigina

National Qualifications Agency, Ukraine, Kyiv

semigina.tv@gmail.com

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5677-1785

Abstract. A strengths-based perspective puts the resources of individuals, families, communities, and their environments, rather than their deficit needs, problems and pathologies, at the center of the social work helping process.

This research was aimed at evaluating the effectiveness of an intervention developed on the basis of an approach based on the strengths of families raising children with autism in improving the family life quality, strengthening its capacity, expanding their rights and possibilities, and enhancing resilience.

The experimental intervention was carried out at the Educational and Rehabilitation Center for Children with Autism “Dovira” (Lviv, Ukraine) and consisted of 12 group meetings. It had one experimental group (30 people) and two control groups (60 people).

The results of pre- and post-intervention surveys demonstrate the encouraging evidences of the effectiveness of the strength-based intervention program in social work with families raising children with autism, which indicates the possibility of its application in the family social work practice, in particular with families raising children with autism and other developmental disorders.

Keywords: strengths-based perspective, family social work, stigma, social work intervention, experimental design.

Received: 14/09/2022. Accepted: 15/2/2022

Copyright © 2022 Olha Stoliaryk, Tetyana Semigina. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

Modern social work is based on values that determine the quality of life of an individual or a social group as the leading goal of social work and the result of practical activity. Achieving this goal is possible thanks to the development of social justice, the strengthening of individual rights, the expansion of rights and the strengthening of collective responsibility, the development of the inclusiveness of the social environment, which is manifested in respect for diversity (IASSW, 2018).

Currently, in various societies, there are social groups that are discriminated against, stigmatized, or are in institutional isolation due to limited access to services available in the community. Such groups include families raising children with mental illnesses, in particular with autism (Izadi-Mazidi, Riahi, & Khajeddin, 2015; Parker, Diamond, & Del Guercio, 2020; Whittingham et al., 2009).

The analysis of the Ukrainian academic discourse of social work regarding the support of families raising children with autism demonstrates the obsolescence of technologies, forms and methods of practical interventions, which are oriented towards a paternalistic approach and devaluing the role and participation of family members, their ability to improve their own well-being. Existing practices can be considered fragmented and cover a small proportion of families, which indicates the lack of systemic social support and the inefficiency of local social policy (Semigina & Chistyakova, 2020; Stoliaryk & Semigina, 2020).

The withdraw of Ukraine from the medical model of disability, the implementation of the deinstitutionalization policy, which involves the transformation of institutional care facilities where children with autism and other mental health problems were located until recently, and the need to develop the inclusiveness of communities pose new challenges to social work with families raising children with autism (Stoliaryck, Semigina, & Zubchyk, 2020). An important role is given to expanding the rights and opportunities of families as a tool to ensure their access to services available in the community and society, which, in turn, determines the extent of their social integration.

The purpose of our work was to develop and pilot the intervention for parents. So, our research was aimed at evaluating the effectiveness of an intervention developed on the basis of an approach based on the strengths of families raising children with autism in improving the family life quality, strengthening its capacity, expanding their rights and possibilities, and enhancing resilience.

Social Work Interventions for Families Raising a Child with Autism: Theoretical Framework

In this research, the family social work model (Stoliaryck et al., 2020) was employed for constructing the content and procedures of helping activities for parents.

The academic literature proposes diverse methodological approaches to building interventions with families. In particular, some researchers (Chiang, 2014; Grant, Rodger, & Hoffmann, 2016; Hall & Graff, 2011) emphasize the use of psychological education for parents raising children with autism, the main purpose of which is to inform family members about the needs and services offered by service institutions, the features of raising a child with autism nosology, lectures for parents on improving competence, etc.

Along with psychological education, researchers suggest using cognitive behavioral therapy (Anclair et al., 2017; DuBay, Watson, & Zhang, 2018). It considers the focus of parents’ thinking as determining their behavior and actions in response to life influences. The way of thinking is either positive or negative, it affects the assessment and attitude to the situation in which the family finds itself and the coping strategies that family members choose when solving life difficulties. The work on the assessment of the current situation in which the family is located and the analysis of past experiences that influenced the assessment of their own lives has an important role. Awareness and capabilities raising parental trainings are viewed as the important element of social work with families having a child with mental health problems and social development of a child (Kaiser & Roberts, 2013; Whittingham et al., 2009; Xu, 2019).

Academics also advocate working with the stress that families live through and which is associated with the child’s diagnosis, the need for regular care, parenting difficulties, and overwork. According to Neece (2014) and Dababnah et al. (2018), among popular techniques and tools there are the mindfulness practices, that form a sense of “here and now”, understanding the reactions of your body, positive affirmations, meditation for restoring psychological and emotional comfort, changing the focus of thinking, and focusing on your feelings . Along with mindfulness practices, forecasting and planning techniques are used (Freedman et al., 2012). They are focused on goal setting and roadmaps creation of close prospects that allow the family to see the available resources and set achievable goals for them, building their trajectory to achieve them.

While creating social work intervention, special attention should be paid to the methods of structured and strategic family therapy (Hoffman et al., 2009; Parker et al., 2020; Parker & Molteni, 2017). Such therapy involves restructuring relationships in family subsystems, changing family coping strategies, focusing family efforts on solving family problems, constructive communication and interaction.

The analysis of the interventions aimed at social support for parents highlights both their strengths and weaknesses (Stoliaryk & Semigina, 2020). Researchers pointed out the necessity for a combination of diverse social work methods and technologies, which focus on encouraging family members, positive identification, self-confidence and capabilities, focusing the available resources of the family in improving the quality of life, which is consonant with the use of an approach focused on the clients’ strengths in social work. The effectiveness of collaborative interventions based on the strengths perspective used for the families raising children with autism was studied by Lee (2020), Parker et al. (2020), Steiner (2011) and others. Their findings evidence the improvements in capability of parents raising a child with autism.

However, in Ukraine, this approach has not been sufficiently studied and has not been used in the practice of social work with families raising children with developmental disabilities. This was the impetus for an experimental intervention development based on the principles and methods of an approach focused on the strengths of the family.

It is also worth to mention the concept of the quality of life of a family. It became rather widespread in the academic literature and constitutes one of the key theoretical perspectives in modern social work. Among all diverse approaches to understanding peculiarities of family well-being (Benjak, 2011; Brown et al., 2009; Hoffman et al., 2006), we picked up Zuna’s theory of family quality of life (Zuna, Turnbull & Summers 2009). It claims that such family parameters as characteristics of the child, availability of services, social mobility and activity of the family, family relations and interaction, parental competence, social support, resources as well as socio-demographic characteristics play crucial role in family well-being.

The Strenght-Based Pilot Intervention for Parents

In 2021–2022, with regard to theoretical framework dscribed above, we deleloped a new strengths-based intervention. The intervention was aimed to develop internal resources and resilience of the families raising children with autism.

The following core areas of the intervention based on clients’ strengths were defined:

1) a sense of social belonging and engagement, which provided the family’s informational inspiration, inclusion in social networks by establishing cooperation between specialists involved in autism problems and the family, reducing stigma and supporting the family’s socialization by developing adaptive and “soft” skills of their members (financial literacy, goal setting, time and self-management);

2) family restructuring and transformation of the family value context, which is focused on maintaining positive self-esteem and family members’ identification, recognizing their value and role in solving difficulties and looking at them as such, cultivating a positive scenario for the events’ development and encouraging initiative to act. Obstacles and difficulties are seen as such that the family can solve and as the means for building resilience in life. An important role is given to rethinking the meaning of difficulties, facilitating cause/effect assessment, and managing stress;

3) the family system’s reorganization, which was aimed at combining the resources and strengths of each family member to meet their individual (personal) needs and the general needs of the family. A significant role is assigned to rethinking the context of the existing life situation, identifying such family’s weaknesses as a growth zone, establishing a balance between the family’s functioning areas (career, social ties, family responsibilities), developing flexibility and readiness for changes (the ability to reorganize in case of a negative outcome).

4) focus on communication and constructive interaction to change the life situation by developing emotional intelligence, empathy.

The experimental intervention is intended to be implemented for three months. It consists of weekly group training meetings lasting 2.5 hours each. These meetings have their own purpose and an objective, methods and tools of work. The training is divided into several modules: (1) family adaptive skills; (2) family restructuring and the organizational model of the family; (3) focus on family resources and solutions (Table 1).

Table 1

The content of an intervention designe based on a client strengths-based approach

|

Task |

Content |

Time |

|

MODULE I. ADAPTIVE FAMILY SKILLS |

||

|

Empowerment |

Group session 1. Introduction. Creating roadmaps to support autism. |

2.5 hours |

|

Group session 2. Development of cooperation readiness (search for supporting systems). |

3.5 hours |

|

|

Reducing stigma. Social mobility and activity. |

Group session 3. Development of professional mobility and financial literacy. |

2.5 hours |

|

Group session 4. Removing stigma and institutional mobility, increasing social activity. |

2.5 hours |

|

|

Group session 5. Self and time management. Development of social and “soft” skills. |

2.5 hours |

|

|

MODULE II–III. FAMILY RESTRUCTURING AND FAMILY ORGANIZATIONAL MODEL |

||

|

Reorganization of relations in family subsystems and the value context transformation

|

Group session 6. Mediation in conflict resolution, stress relief, balancing family resources and needs. Gender equality. |

2.5 hours |

|

Group session 7. Restructuring of the family system, everyday life planning and family routines’ coordination. Reframing family roles. |

2.5 hours |

|

|

Group session 8. Developing partner understanding skills, skills of active listening and empathy. Productive communication. Consolidation of positive interaction, positive family scenarios. |

2.5 hours |

|

|

Parent self- |

Group session 9. Formation of a parenthood positive image, the concept of “I am the father/mother”. Rational allocation of resources and participation of both parents in the parenting process. Replacing interaction patterns and synchronizing emotional responses. |

2.5 hours |

|

Group session 10. Parental competence and self-efficacy. Reduced autostigma. The family role’s self-assessment and a positive maternal/paternity scenario. |

2.5 hours |

|

|

MODULE IV. FAMILY RESOURCE ORIENTATION AND SOLUTIONS |

||

|

Formation of life stability, resources’ empowerment, conscious choice |

Group session 11. Accepting the situation and making sense of difficulties. Formation of positive prospects for the life scenario development. |

2.5 hours |

|

Group session 12. Working with internal experiences. Coping strategies and informed choice. |

2.5 hours |

|

Methodology of Research

Research process

The research employs the experimental, statistical methodology using quantitative research methods. Thus the research process was arranged in the following standard stages:

1) selection of one experimental (E1) and two control (K1, K2) groups;

2) a pre-intervention survey assessing the life quality of families in all groups of participants;

3) implementing the intervention with group E1 at the Training and Rehabilitation Center “Dovira” in Lviv (Ukraine);

4) post-intervention survey assessing the life quality of families in all groups of participants;

5) comparison of the pre-intervention and post-intervention survey results by analyzing the Student’s t-criterion for a dependent sample to identify the intervention’s impact.

Participants

The Dovira centre does not have any medical services, only social services for children with autism. The experimental group (E1) was formed from families receiving consultation services on an irregular basis in Dovira.

The research also had two control groups:

K1 — families accompanied by the local public social services center;

K2 — families whose children are in the Dovira rehabilitation center and receiving regular services but did not participate in the pilot intervention.

Criteria for the selection of research participants were the following:

• having a child under the age of 18 with an officially registered autism diagnosis (ASD);

• be a client (recipient) of services in: a) the Dovira educational and rehabilitation center; b) consultative and inclusive resource center, c) Lviv city center of social services for families, children and youth;

• consent to participate in the research.

Questionnaire

Based on the the Zuna’s concept of family quality of life (Zuna et al., 2009) and other scholarly literature we had developed the questionnaire and used it for evaluation of the effectiveness of the piloted intervention.

The questionnaire includes 115 open and closed questions to measure self-perception of quality of life. It embraces the following aspects:

• characteristics of the child, nosology of autism, behavioral and communication disorders, routines, the process of establishing a diagnosis and concomitant diseases related to autism;

• availability of educational, medical, social services through the prism of autism and taking into account the influence of the main obstacles: time, territorial distance, stigmatization, information availability, compliance with the needs of the family and the child;

• social mobility and activity of the family, which includes the professional activity of family members, belonging to communities, organizations and communities, leisure time, social connections;

• family relations and interaction, financial well-being, division of family responsibilities, peculiarities of role relations in the “husband-wife” system;

• synchronization of child-parent emotional, psychological, behavioral reactions, parental competence, upbringing, parental expectations;

• received and requested emotional, psychological, instrumental, social support;

• sychosocial resources, stress, coping strategies;

• social and demographic characteristics of the group: age, education, gender, marital status, place of residence, employment.

The research tool used Likert scale for the majority of questions.

The comparative analysis of the data was processed by paired-samples t-test for the dependent sample. Microsoft Excel and SPSS-22 statistical package were used for this purpose.

Ethical issues

The protocol of the study was approved by the Academy of Labour, Social Relations and Tourism (Kyiv, Ukraine), where Olha Stoliaryk was a PhD student, and Tetyana Semigina was an academic supervisor.

This research is based on the Global Ethical Principles of Social Work Research (IASSW, 2018). In order to avoid erroneous understanding of the experiment’s purpose, prejudice against the process and results of research, participants were provided with a preliminary briefing, where the goals, features of the study were discussed, all of them signed the consent form.

The study had no external funding. There is no conflict of interests or competing interests.

Results of Research

Characteristic of parents and children

Table 2 below contains key social and demographic characteristics of the control and experimental groups for the intervention.

The research involved 90 people raising children with autism living in Lviv (59 people, 65.5 %) and localities of the Lviv oblast (31 people: 23 % – “town”, 11 % – “village”).

Gender breakdown was: men –38 people (42 %), women – 52 (58 %).

The main share of respondents falls on the group of mature age. The following age groups were identified: 18–25 years – 3 persons (3 %); 26–34 years – 22 (24 %) persons; 35–44 years – 51 (57 %) persons; 45–60 years – 14 (16 %) persons.

Two of the participants indicated that they have a PhD.; 41 persons (46 %) of the respondents have “full higher education”, 11 persons (12 %) have “incomplete higher education”, 28 persons (31 %) have “vocational and technical education”, and 8 persons (8 %) have completed “general secondary education”.

Table 2

Socio-demographic characteristics of the experimental and control groups

|

Total number (amount) (n=90) |

E1 (n=30) |

K1 (n=30) |

K2 (n=30)* |

|

Gender (sex) |

|||

|

Men |

11 |

14 |

13 |

|

Women |

19 |

16 |

17 |

|

Education |

|||

|

Academic degree |

1 |

1 |

- |

|

Complete higher education |

16 |

11 |

14 |

|

Incomplete higher education |

1 |

4 |

6 |

|

Vocational education and training |

12 |

7 |

9 |

|

General secondary education |

- |

7 |

1 |

|

Residence |

|||

|

City |

12 |

25 |

22 |

|

Village |

16 |

2 |

3 |

|

Urban-type settlement |

2 |

3 |

5 |

|

Age |

|||

|

18 – 24 |

1 |

- |

2 |

|

25 – 34 |

8 |

6 |

8 |

|

35 – 44 |

18 |

17 |

16 |

|

45 – 60 |

3 |

7 |

4 |

* Notes: E1 – experimental group (participants of the piloted intervention); K1 – control group (user of public social services); K2– control group (regular users of Dovira Centre).

Participants have children with autism whose age vary from 3 to 17 years old.

20 parents (22.3%) of 90 research paricipants reported that their children had verbal communication, 34 (33.4%) – had partial communication. All other parents selected option: alternative communication (12.3%), body language communication (18.8%), no intecation at all (8.8%). As for behavioral aggression, parents selected the following expression of aggression: verbal (25.2%), physical (18.8%), instrumental (18.8%), self-agression (11.2%) and so on. One third of respondents mentioned the children adhetence to routine.

Findings from the pre-intervention survey

A pre-intervention survey found that families raising children with autism experience difficulties in all areas of family functional ability (Semigina & Stoliaryk, 2022).

Families have difficulty interacting with service organizations related to autism issues and need an intervention that will contribute to expanding their rights and possibilities. Family members show signs of lost mobility in the public relations system. Therefore, even if there is an opportunity to be engaged in professional activities, a significant proportion of the subjects are not employed. Family members have frustrated social contact needs, tend to segregate with social groups that are similar in characteristics to them, avoid inclusion in community life, and have a passive social life that depends on the needs of a child with autism.

The family system undergoes functional changes after the birth of a child with autism. In particular, a significant proportion of the subjects suffer from conflicts in the family, hidden resentments against the partner, a decrease in the quality of intimate life, lack of time for family traditions, and pathological dependence on a child with autism. Families show reduced educational potential and low indicators of parental competence.

According to the research results, families have quite close social contacts that are able to provide social, psychological, or instrumental support in the process of raising a child, however, due to feelings of guilt and shame, biased attitudes to the ability of others to understand the needs of a child with autism, only a small part of them initiates the desire to use the available help. A significant number of families are in a state of chronic stress and depression and suffer from health problems.

Findings from the post-intervention survey

The comparision of the average values of indicators (comparative analysis by the Student’s paired t-criterion for a dependent sample) demonstrates the significant statistical differences in the results of the experimental E1 group.

The changes indicate that the E1 research groups gave a higher rating to the available services in the region (educational, rehabilitation, social) during re-measurement, they are more open to cooperation with them (they take into account the specialists’ recommendations, have information about the services provided and used by institutions, highly assess the attitude of professionals to the needs of the child and family, the indicators of the number and frequency of visits to institutions have increased) (Table 3).

Table 3

Assessment of social activity and mobility in the pre- and post-experimental period in the experimental and control groups (dependent t-test for paired samples)

|

Value |

Factor Loading (М) |

|||||

|

Pre-intervention (1) |

Post-intervention (2) |

|||||

|

К1 |

К2 |

Е1 |

К1 |

К2 |

Е1* |

|

|

Social life activity |

2.73а |

2.76а |

2.86 |

2.73а |

2.76а |

3.50 |

|

The need for assistance and help |

.63 |

1.76а |

2.26 |

.70 |

1.76а |

1.50 |

|

Lack of time for the favorite activities and hobbies |

1.33а |

2.36а |

2.63 |

1.33а |

2.36а |

2.03 |

|

The need for communication |

3.40а |

2.46 |

2.60 |

3.40а |

2.53 |

2.16 |

|

Presence of stigma/autostigma |

2.80а |

3.13а |

3.23 |

2.80а |

3.13а |

2.73 |

|

A sense of social inclusion |

2.60а |

2.83а |

2.76 |

2.60а |

2.83а |

3.63 |

|

Opportunity to be engaged in professional activities |

2.76 |

3.13а |

2.60 |

2.80 |

3.13а |

3.30 |

|

Involvement in community’s life |

.76а |

2.10а |

2.16 |

2.03а |

2.10а |

2.90 |

* Notes: E1 – experimental group (participants of the piloted intervention); K1 – control group (user of public social services); K2- control group (regular users of Dovira Centre).

There are statistically significant discrepancies in the parameters for assessing social activity and family mobility in virtually all indicators of the experimental E1 group (р ≤ .05). Thus, there was a significant increase in the following indicators: (1) social life became more active; (2) participation in public events expanded, as well as participation in the cultural and/or religious community; (3) a sence of social inclusion improved; (4) ability and desire to engage in professional activities ameliorated.

The experimental group participants’ self-assessment allows stating the decrease of the following indicators:

• the need for assistance in child care (M = .23, SD = .62, σ = .11, t-criterion = 2.41, р = .004);

• weakening of the feeling of lack of communication with socially desirable contacts (M = .36, SD = .49, σ = .89, t-criterion = 4.09, р = .000);

• sense of stigma (M = .50, SD = .90, σ = .16, t-criterion = 3.04, р = .005).

At the same time, no significant differences were found in both control groups.

While comparing the indicators for marital relations assessment, minor changes were found (p ≥ .05) in the first control group, in particular, the fact of an increase in the indicator of lack of time for spouses’ personal affairs (M = .66, SD = .25, σ = .46, t-criterion = 1.43, р = .161), insufficient degree of parental duties’ performance (M = .33, SD = .18, σ = .33, t-criterion = 1.00, p = .326), lack of joint planning and budget allocation (M = .66, SD = .25, σ = .46, t-criterion = 1.43, р = .161), an increase in cold, indifference and tension in the relationship, and the number of hidden resentments against the partner (M = .33, SD = .18, σ = .33, t-criterion = 1.00, p = .326) (Table 4).

Table 4

Assessment of marital relationships before and after the intervention in the experimental and control groups (dependent t-test for paired samples)

|

Values |

Factor Loading (М) |

|||||

|

Pre-intervention (1) |

Post-intervention (2) |

|||||

|

К1 |

К2 |

Е1 |

К1 |

К2 |

Е1* |

|

|

Focusing family life on the needs of the child |

3.36а |

3.20 |

3.10 |

3.36а |

3.26 |

1.60 |

|

Lack of common time for spouses |

3.46а |

3.33а |

3.03 |

3.46а |

3.33а |

2.20 |

|

Conflicts and disputes |

3.66а |

3.23а |

3.36 |

3.66а |

3.23а |

1.76 |

|

Self-control loss, negative emotions |

1.80а |

2.43 |

2.70 |

1.80а |

2.50 |

1.36 |

|

Reduced quality of intimate life |

2.16а |

2.33а |

2.86 |

2.16а |

2.33а |

1.80 |

|

Joint routines distribution between spouses |

2.30а |

2.26а |

2.53 |

2.30а |

2.26а |

1.46 |

|

Cold, indifference, tension in relationships |

.70 |

1.90а |

2.56 |

.73 |

1.90а |

1.50 |

|

Isolation from family relationships |

2.03а |

2.60а |

2.90 |

2.03а |

2.60а |

1.56 |

* Notes: E1 – experimental group (participants of the piloted intervention); K1 – control group (user of public social services); K2– control group (regular users of Dovira Centre).

Analysis of indicators shows a negative result in the second control group of subjects (K2). Therefore, minor statistical discrepancies (р ≥ .05) for the growth (↑) were revealed by the following parameters: focusing the daily routines of spouses on the needs of a child with autism (M = .66, SD = .25, σ = .46, t-criterion = 1.43, р = .161), an increase in the loss of self-control, negative emotions, in particular aggression, anger (M = .66, SD = .25, σ = .46, t-criterion = 1.43, р = .161) and increased financial difficulties in the family (M = .66, SD = .25, σ = .46, t-criterion = 1.43, р = .161).

Statistically significant differences were found in the experimental group (E1). Consequently, there were significant changes in decreasing (↓) the indicators for the following parameters (p ≤ .05):

• reducing the focus of family life on the needs of a child with autism (M = 1.50, SD = 1.16, σ = .21, t-criterion = 7.04, р = .000);

• reducing the number of conflicts and disputes affecting interpersonal communication between spouses (M = 1.60, SD = .93, σ = .17, t-criterion = 9.40, р = .000);

• improving self-control and reducing negative emotions (anger, aggression) (M = 1.33, SD = 1.06, σ = .19, t-criterion = 6.88, р = .000);

• improving the quality of partners’ sexual life (M = 1.06, SD = 1.04, σ = .19, t-criterion = 5.57, р = .000);

• normalizing the family microclimate due to a decrease in indifference between partners (M = 1.06, SD = 1.04, σ = .19, t-criterion = 5.57, р = .000);

• reducing the fear of repeated pregnancy due to existing experience (M = .40, SD = .85, σ = .15, t-criterion = 2.56, p = .016).

The results of a comparative analysis indicate an improvement in the field of family (marital) relationships of the E1 group after participation in the intervention.

The results of comparative analysis of indicators for assessing relations with a child are included in Table 5.

Table 5

Assessment of parental competence before and after the intervention in the experimental and control groups (dependent t-test for paired samples)

|

Values |

Factor Loading (М) |

|||||

|

Pre-intervention (1) |

Post-intervention (2) |

|||||

|

К1 |

К2 |

Е1 |

К1 |

К2 |

Е1* |

|

|

Personalization of guilt |

1.30а |

2.20а |

2.03 |

1.30а |

2.20а |

1.36 |

|

Loss of self-control, aggression towards the child |

2.53а |

2.80 |

2.80 |

2.53а |

2.83 |

1.60 |

|

Low parental competence |

2.76а |

2.56а |

2.63 |

2.76а |

2.56а |

1.36 |

|

Synchronization of father (mother) and child emotions |

1.03 |

2.23а |

2.30 |

1.06 |

2.23а |

1.53 |

|

Cultivating child behavior |

3.00а |

2.40а |

2.73 |

3.00а |

2.40а |

1.73 |

|

Accepting a child’s diagnosis |

2.06 |

2.30а |

3.06 |

2.10 |

2.30а |

1.70 |

|

Fixing on the past while searching for the diagnosis’ cause |

2.20а |

2.60а |

2.73 |

2.20а |

2.60а |

1.56 |

|

Autostigma |

3.03а |

3.40 |

3.73 |

3.03а |

3.53 |

3.40 |

|

Fear of the future, blurred prospects |

3.10а |

3.53 |

2.76 |

3.10а |

2.50 |

3.13 |

* Notes: E1 – experimental group (particiants of the piloted intervention); K1 – control group (user of public social services); K2 – control group (regular users of Dovira Centre).

Findings for the experimental group E1 indicate statistically significant downward discrepancies (↓) in the following parameters (p ≤ .05):

• reducing the child’s sense of stigmatization by the external environment (M = 1.13, SD = .89, σ = .16, t-criterion = 6.90, р = .000), and, as a result, a sense of autostigma (M = .33, SD = .66, σ = .12, t-criterion = 2.76, р = .010);

• emotional synchronization between the subjects and the child (M = .76, SD = .77, σ = .14, t-criterion = 5.42, р = .000);

• reducing dependence on the child (M = .63, SD = .96, σ = .17, t-criterion = 3.59, р = .001);

• reducing distance from the child (M = 1.20, SD = .88, σ = .16, t-criterion = 7.41, р = .000);

• reducing sense of individuality (M = .43, SD = .85, σ = .15, t-criterion = 2.76, р = .010),

• reducing fixation on the past while searching for the diagnosis’ cause (M = 1.16, SD = .98, σ = .17, t-criterion = 6.48, р = .000) and fear of future prospects (M = .63, SD = 1.27, σ = .23, t-criterion = 2.73, р = .011);

• self-control growth (M = 1.20, SD = .76, σ = .13, t-criterion = 8.63, р = .000) and

• improved sense of parental competence (M = 1.26, SD = 1.08, σ = .19, t-criterion = 6.42, р = .000).

No statistically significant differences were found in the two control groups K1 and K2.

Table 6 presents comparison of indicators for assessing the available social support.

Findings in the experimental group (E1) demonstrate statistically significant and essential differences (р ≤ .05) in the parameters:

• growth (↑) of assistance from close social contacts in raising a child (M = .60, SD = .72, σ = .13, t-criterion = 4.53, р = .000); (↑)

• the possibility to leave the child to someone from close social contacts for temporary care (M = .50, SD = .57, σ = .10, t-criterion = 4.78, р = .000);

• increasing the delegation of parental responsibilities to the third parties (M = .83, SD = 1.04, σ = .19, t-criterion = 4.20, p = .000);

• increasing sense of unbiased attitude (M = .93, SD = .86, σ = .15, t-criterion = 5.88, p = .000); (↑) the ability of the subjects to accept the necessary social support from the third parties (M = .93, SD = .86, σ = .15, t-criterion = 5.88, p = .000);

• increasing of emotional and psychological support received from the inner circle (M = .60, SD = .56, σ = .10, t-criterion = 5.83, р = .000).

Comparative analysis of the obtained data showed that there were no significant discrepancies in the first (K1) and second control (K2) groups.

Table 6

Assessment of social support before and after the intervention in three groups in the experimental and control groups (dependent t-test for paired samples)

|

Values |

Factor Loading (М) |

|||||

|

Pre-intervention (1*) |

Post-intervention (2*) |

|||||

|

К1 |

К2 |

Е1 |

К1 |

К2 |

Е1* |

|

|

Availability of persons who can provide support |

1.63а |

2.80 |

2.76 |

1.63а |

2.86 |

3.06 |

|

Availability of child care assistance |

3.06а |

3.46а |

3.00 |

3.06а |

3.46а |

3.50 |

|

Delegation of responsibilities to others if necessary |

2.30а |

2.86а |

2.56 |

2.30а |

2.86а |

3.40 |

|

Lack of a sense of bias |

1.36 |

2.10а |

2.13 |

1.43 |

2.10а |

3.06 |

|

Family’s ability to receive social support |

1.20 |

2.40а |

2.30 |

1.23 |

2.40а |

3.23 |

|

Impact of social support on family life quality |

2.16а |

2.50а |

2.10 |

2.16а |

2.50а |

2.53 |

|

Availability of psychological support |

2.63а |

2.96 |

3.06 |

2.63а |

3.06 |

3.66 |

* Notes: E1 – experimental group (participants of the piloted intervention); K1 – control group (user of public social services); K2– control group (regular users of Dovira Centre).

The post-intervention survey also allows stating that in the experimental group E1 the following changes are observed:

• a decrease in feelings of anxiety, obsessive fears and panic attacks (M = 1.53, SD = .89, σ = .16, t-criterion = 9.33, р = .000);

• improvement of psychosomatics (M = .83, SD = .98, σ = .17, t-criterion = 4.63, р = .000);

• reduction of social isolation, avoidance of difficulties (M = 2.10, SD = .75, σ = .13, t-criterion = 15.15, р = .000);

• a decrease in the sense of such circumstances that cannot be changed (M = 1.33, SD = .88, σ = .16, t-criterion = 8.26, р = .000);

• a decrease in a sense of unfulfilled expectations (M = 1.66, SD = .64, σ = .11, t-criterion = 9.86, р = .000).

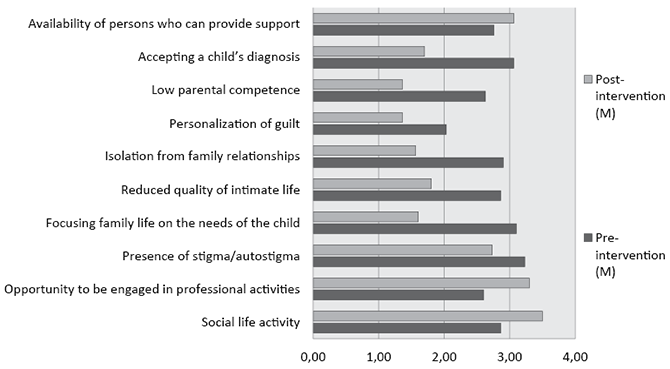

All in all, the evaluation of the pilot programme’s effectiveness indicated an improvement in the experimental group. There was an increase in the assessment of interaction with educational, medical, social institutions according to the indicators of cooperation presence between specialists and family members, taking into account the recommendations of the family staff, the institutions’ policy sensitivity to the needs of a child with autism, a decrease in stigma and autostigma in family members. We can also observe an increase in the amount of time and a decrease in territorial, information barriers, which indicates the family opportunities’ expansion. The family mobility indicators have also increased (it is characterized by the number and quality of interactions with social contacts, a decrease in social isolation, an increase in participation in community life, a decrease in the need of help and assistance). The married life’s self-assessment has improved: the number of conflicts has decreased, the number of hidden resentments has decreased, understanding and productive cooperation between partners has increased, the quality of intimate life has improved. We can also note that the parental competence indicators have increased, the threshold for problems of relations with the child emotional synchronization, dependence on the child’s needs and the desire for distancing have decreased (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Self-assessment of family quality of life by participants of the experimental group before and after the intervention (difference in mean values, М)

The important change is related to the ability of families to be aware of and use available social support. The findings evidence that it has increased, while the network of support systems enlarged. At the same time, feelings of shame and guilt experienced in situations of seeking help have diminished. Family members indicated positive changes in social and psychological well-being, in particular, reduction of stress and depression signs, and improvement of physical well-being.

Discussions

Findings from the post-intervention survey prove the effectiveness of the pilot intervention focused on the strengths of families raising children with autism.

We are aware of limitations of our study. The first limitation is the sampling procedure. The participants were recruited through convenience sampling; thus, the results are not representative of the general population (actually, there are no data on the number of people or children with autism on the national or regional level). So, the overall characteristics of our sample do not allow us to draw broader claims. Secondly, our findings are limited by mono-method (a survey) and self-reporting biases. But we hope our study adds a layer in understanding the feasible innovative services for families who experience challenges in raising children with specific problems.

It is worth mentioning that our research is in line with results of other parental interventions aimed at changes of family self-perception and abilities to tackle the challenges (Al-Khalaf, Dempsey & Dally, 2014; Banach et al., 2010; Casagrande & Ingersoll, 2017; Drolet, Paquin & Soutyrine, 2007; Pennefather et al., 2018; Todd et al. 2010). Yet, our observations from piloting the intervention push us to state that social work based on strengths should only be used when the family is ready for changes. It is also proved by the research with other social work clients (Bozic, Lawthom & Murray, 2018; Bu & Duan, 2021; Cheng, Chair & Chau, 2018).

Our findings, as well as findings from other studies (Saleebey, 1996; Shochet et al., 2019; Steiner, 2011) indicate that the inspiration that underlies the approach is not able to work when the family is passive, unmotivated. Enthusiasm, on the one hand, serves as a way for increasing the assets of families raising children with autism, helps to expand their rights and opportunities by activating their life position, and, on the other hand, acts as a method of public opinion transformation and the basis for interventions that allow the family resisting the negative influences of the social environment, structural and political changes.

Social workers who build their practices on the approach should view the risks and life challenges of families not as an obstacle, but as means that should be carefully studied together with clients. That is, the “consumer’s experience” is important, in the light of which you can understand what is important for the family in a particular situation (Hammond, 2010). Interventions based on the strengths approach are not only a result (the family’s life position and resource potential activation) but also a process (which path should be chosen for the best possible results of solving the situation). Therefore, it is necessary to take into account the following while planning the process: the focus of intervention (emphasis on the family’s strength, not on the life situation), the language of a positive image (departure from the judgments, negative statements of not only the social work specialist but also the family members; transformation of negative expressions into positive ones), family assessment of the situation frameworks, family support by consolidating the forces of all participants in the process. It is worth to keep in mind that the change process is dynamic and takes time. Changes should start with the least traumatic ones for the family. Leaving the comfort zone is a risk because it invites family members to destroy ready-made patterns of their response to typical or atypical situations

Social workers who use a customer-centric approach in family social work should take into account the risk of an unconditional alternative belief in the family’s potential. A specific circumstance can create ethical dilemmas while working with clients since it implies a full (unconditional) acceptance of the client’s inner world and partial or complete agreement with his/her values, statements, thoughts, and life position. Social workers may not share the client’s choice or not have enough faith in the family’s resource potential, they also have to perceive and understand family’s weakness.

In order to develop sustainable skills, the intervention cannot last less than three months, which limits the use of the approach in urgent (emergency) or short-term clients’ social support technologies. At the same time, social workers cannot predict how families will behave after they get out of social support.

Social work practitioners should understand that using this approach is not able to reduce the external environment’s impact on the family, but only to change the family members’ assessment, attitude, or reaction to these influences. It is important to take into account the historical context of social work with families raising children with developmental disabilities and the structural inequality of clients and needs to be given authority, such as the ability to influence the process of forming social policies and services provided.

Conclusions

The research provided evidences that the intervention programme using a perspective based on family strengths as the main framework was effective in improving the overall assessment of the life quality of families raising children with autism. This intervention was aimed to develop internal resources and resilience of the families raising children with autism and included such modules, as: a sense of social belonging and engagement, family restructuring and transformation of the family value context, the family system’s reorganization, focus on communication and constructive interaction.

Quantitative data based on total of 90 parents divided into experimental and control groups demonstrated self-reported improvements in the following: interaction with service institutions, relationships in family subsystems, parental competence, the ability in receiving social support, building the family’s adaptive potential by developing resilience skills and coping strategies for overcoming difficulties, as well as social, psychoemotional well-being among family members. This may serve as an impetus for the inclusion of interventions based on the client’s strengths in the family social work practice and further study of its application for the different types of social work clients.

References

Al-Khalaf, A., Dempsey, I., & Dally, K. (2014). The effect of an education program for mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder in Jordan. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 36(2), 175–187. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10447-013-9199-3

Anclair, M., Lappalainen, R., Muotka, J., & Hiltunen, A. J. (2017). Cognitive behavioural therapy and mindfulness for stress and burnout: a waiting list controlled pilot study comparing treatments for parents of children with chronic condition. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 32, 389–396. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12473.

Banach, M., Iudice, J., Conway, L., & Couse, L. J. (2010). Family support and empowerment: post Autism diagnosis support group for parents. Social Work with Groups, 33(1), 69–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/01609510903437383.

Benjak, T. (2011). Subjective quality of life for parents of children with autism spectrum disorders in Croatia. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 6(1), 91–102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-010-9114-6.

Bozic, N., Lawthom, R., & Murray, J. (2018). Exploring the context of strengths – a new approach to strength-based assessment. Educational Psychology in Practice, 34(1), 26–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/02667363.2017.1367917.

Brown, H. K., Ouelelette-Kuntz, H., Hunter, D., Kelley, E., Cobigo, V., & Lam, M. (2011). Beyond an autism diagnosis: Children’s functional independence and parents’ unmet needs. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41, 1291–1302. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-010-1148-y

Bu, H., & Duan, W. (2021). Strength-Based Flourishing Intervention to Promote Resilience in Individuals with Physical Disabilities in Disadvantaged Communities: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Research on Social Work Practice, 31(1), 53–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731520959445.

Casagrande, K. A., & Ingersoll, B. R. (2017). Service delivery outcomes in ASD: Role of parent education, empowerment, and professional partnerships. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26(9), 2386–2395. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0759-8.

Cheng, H. Y., Chair, S. Y., & Chau, J. P. C. (2018). Effectiveness of a strength-oriented psychoeducation on caregiving competence, problem-solving abilities, psychosocial outcomes and physical health among family caregiver of stroke survivors: A randomised controlled trial. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 87, 84–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.07.005.

Chiang, H. (2014). A parent education program for parents of Chinese American children with autism spectrum disorders (ASDs): a pilot study. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 29(2), 88–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088357613504990.

Dababnah, S., Rizo, C. F., Campion, K., Downton, K. D., & Nichols, H. M. (2018). The relationship between children’s exposure to intimate partner violence and intellectual and developmental disabilities: a systematic review of the literature. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 123(6), 529–544. https://doi.org/10.1352/1944-7558-123.6.529.

Drolet, M., Paquin, M., & Soutyrine, M. (2007). Strengths-based approach and coping strategies used by parents whose young children exhibit violent behaviour: Collaboration between schools and parents. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 24(5), 437–453. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-007-0094-9.

DuBay, M., Watson, L. R., & Zhang, W. (2018). In search of culturally appropriate autism interventions: Perspectives of Latino caregivers. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(5), 1623–1639. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3394-8.

Freedman, B. H., Kalb, L. G., Zaboltsky, B., & Stuart, E. A. (2012). Relationship status among parents of children with autism spectrum disorders: A population-based study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42, 539– 548. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-011-1269-y.

Grant, N., Rodger, S., & Hoffmann, T. (2016). Intervention decision‐making processes and information preferences of parents of children with autism spectrum disorders. Child: Care, Health and Development, 42(1), 125–134. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12296.

Hall, H. R., & Graff, J. C. (2011). The relationships among adaptive behaviors of children with autism, family support, parenting stress, and coping. Issues in Comprehensive Pediatric Nursing, 34, 4–25. https://doi.org/10.3109/01460862.2011.555270.

Hammond, W. (2010). Principles of strength-based practice. Resiliency Initiatives, 12(2), 1–7.

Hoffman, C. D., Sweeney, D. P., Hodge, D. et al. (2009). Parenting stress and closeness: Mothers of typically developing children and mothers of children with autism. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 24(3), 178–187. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088357609338715.

Hoffman, L., Marquis, J., Poston, D., Summers, J. A., & Turnbull, A. (2006). Assessing family outcomes: Psychometric evaluation of the beach center family quality of life scale. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68(4), 1069–1083. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00314.x.

IASSW (2018). Global Social Work Statement of Ethical Principles. https://www.iassw-aiets.org/2018/04/18/global-social-work-statement-of-ethical-principles-iassw. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199975839.013.201.

Izadi-Mazidi, M., Riahi, F., & Khajeddin, N. (2015). Effect of cognitive behavior group therapy on parenting stress in mothers of children with autism. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, 9(3). e1900. http://doi.org/10.17795/ijpbs-1900.

Kaiser, A. P., & Roberts, M. Y. (2013). Parent-implemented enhanced milieu teaching with preschool children who have intellectual disabilities. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 56(1), 295–309. https://doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2012/11-0231

Lee, E. A. L., Black, M. H., Falkmer, M., Tan, T., Sheehy, L., Bölte, S., & Girdler, S. (2020). “We Can See a Bright Future”: Parents’ Perceptions of the Outcomes of Participating in a Strengths-Based Program for Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50, 3179–3194. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04411-9.

Neece, C. L. (2014). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for parents of young children with developmental delays: implications for parental mental health and child behavior problems. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 27(2), 174–186. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12064.

Parker, M. L., Diamond, R. M., & Del Guercio, A. D. (2020). Care coordination of autism spectrum disorder: a solution-focused approach. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 41(2), 138–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2019.1624899.

Parker, M. L., & Molteni, J. (2017). Structural family therapy and autism spectrum disorder: Bridging the disciplinary divide. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 45(3), 135–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/01926187.2017.1303653.

Pennefather, J., Hieneman, M., Raulston, T. J., & Caraway, N. (2018). Evaluation of an online training program to improve family routines, parental well-being, and the behavior of children with autism. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 54, 21–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2018.06.006.

Saleebey, D. (1996). The strengths perspective in social work practice: Extensions and cautions. Social Work, 41(3), 296–305. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/41.3.296

Semigina, T., & Chistyakova, A. (2020). Children with Down Syndrome in Ukraine: Inclusiveness Beyond the Schools. The New Educational Review, 59(1), 116–126. https://doi.org/10.15804/tner.20.59.1.09.

Semigina T., & Stoliaryk O. (2022). “It was a Shock to the Whole Family”: Challenges of Ukrainian Families Raising a Child with Autism. Socialinė teorija, empirija, politika ir praktika, 24, 8–23. https://doi.org/10.15388/STEPP.2022.34

Shochet, I. M., Saggers, B. R., Carrington, S. B., Orr, J. A., Wurfl, A. M., & Duncan, B. M. (2019). A strength-focused parenting intervention may be a valuable augmentation to a depression prevention focus for adolescents with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(5), 2080–2100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-03893-6.

Steiner, A. M. (2011). A Strength-Based Approach to Parent Education for Children with Autism. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 13(3), 178–190. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300710384134.

Stoliaryk, O., & Semigina, T. (2020). Helping families caring for children with autism: what could social workers do? Pedagogical concept and it’s features, social work and linguology. Collective Scientific Monograph. Primedia eLaunch LLC (USA), 14–24. https://doi.org/10.36074/pcaifswal.ed-1.02

Stoliaryck, O., Semigina, T., & Zubchyk, O. (2020). Simeyna sotsialʹna robota: realiyi Ukrayiny [Family social work: the realities of Ukraine]. Naukovyy visnyk Pivdennoukrayinsʹkoho natsionalʹnoho pedahohichnoho universytetu imeni K. D. Ushynsʹkoho, 4, 28-46 (in Ukrainian).

Todd, S. et al. (2010). Using group-based parent training interventions with parents of children with disabilities: a description of process, content and outcomes in clinical practice. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 15(3), 171–175. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-3588.2009.00553.x.

Whittingham, K., Sofronoff, K., Sheffield, J., & Sanders, M. R. (2009). Stepping stones triple Р: An RCT of a parenting program with parents of a child diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 37(4), 469–480. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-008-9285-x.

Xu, Y. (2019). Partnering with families of young children with disabilities in inclusive settings. In: Lo, L., & Xu, Y. (Eds.), Family, School, and Community Partnerships for Students with Disabilities. Advancing Inclusive and Special Education in the Asia-Pacific (pp.3–15). Singapore: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-6307-8_1.

Zuna, N. I., Turnbull, A., & Summers, J. A. (2009). Family quality of life: Moving from measurement to application. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 6(1), 25–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-1130.2008.00199.x.