Social Welfare: Interdisciplinary Approach eISSN 2424-3876

2024, vol. 14, pp. 146–168 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/SW.2024.14.10

The Motivation to Volunteer and Change of Attitudes Towards Volunteering in a Post-Soviet Country

Irma Pranaityte

ISM University of Management and Economics, PhD student

Email: pran.irma@stud.ism.lt

Abstract. The paper explores the attitudes towards volunteering and the change of attitudes towards volunteering in a Post-Soviet country after the collapse of the Soviet regime. The aim of the paper is to reveal what are the factors which keep individuals away from joining voluntary organizations, how the attitude towards volunteering has been changing over 30 years and what motivates individuals to get involved in voluntary organizations. A qualitative research method has been chosen – 60 interviews with individuals who have been born in 1945–1965 and have been living under the Soviet regime. The results reveal the change of attitudes towards volunteering in five periods and how the understanding about volunteering has been changing. Voluntary organizations can use the results of the research for the attraction of potential volunteers to volunteering.

Keywords: Motivation, Volunteering, Compulsory volunteering, Motivation to volunteer, Attitudes towards volunteering

Received: 2023-05-16. Accepted: 2024-11-07

Copyright © 2024 Irma Pranaityte. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

Volunteering, according to Ellis and Noyes (1990:4), was described as actions “in recognition of a need, with an attitude of social responsibility and without concern for monetary profit, going beyond one’s basic obligations.” Volunteering is “recognized as the glue that helps hold societies together and as an additional resource of use in solving social and community problems (Hodgkinson, 2003). Volunteerism is recognized as an important source of sociability, satisfaction, and self-validation over the life course (Hendicks & Cutler, 2004).

Research has been devoted to explain the phenomenon of volunteering, together withnational differences which are directly related with the level of volunteering. Plagnol and Huppert (2009) in their research have found that different rates of volunteering cannot be explained by differences in the social, psychological or social factors associated with volunteering. Results of the research conducted by Parboteeah, Cullen, Lim (2004) show that all forms of capital country wealth, country education, religiosity, societal activism and liberal political regimes have positive relationships with formal volunteering. Gil-Lacruz and Marcuello (2017) research results have shown that the most important differences in level of volunteering lie in the impact of social factors rather than individual characteristics like gender or age. As a cultural and economic phenomenon, volunteering is part of the way societies are organized, how they allocate social responsibilities, and how much engagement and participation they expect from citizens (Anheier, Salamon, 1999). Western countries have very long traditions of volunteering and have a wide range of activities. Differences exist in groups of countries. Volunteering as a formal activity performed for organizations or associations is an older activity in Western Europe, but in Central and Eastern Europe it has been a new phenomenon after the collapse of the communist regime (Sillo, 2016).

At the moment the voluntary sector is researched in different angles. Seeking to understand the nature of this activity, scholars raise the question what are the driving forces of volunteering? Research of Clary and Snyder (1999), Penner and Finkelstein (1998), Black and Jirovic (1999), Okun and Schultz (2003) and others have been focused on motivation of volunteers. After the collapse of the Soviet Union there was a sharp fall in civil organizations and activities, which would be performed for the benefit of the society. How the experience of compulsory activities has influenced the willingness to get involved into voluntary activities, how the attitudes towards volunteering has been changing and how it was associated with the development of voluntary sector.

The aim of this research is to explore the attitudes towards volunteering and their change in a post-Soviet country after the collapse of the Soviet regime, the willingness to get involved in voluntary activities through the organizations.

The qualitative research approach has been chosen for the paper. Participants are individuals, who have been born in 1945–1965 and have been living under the Soviet regime. 60 semistructured interviews have been conducted with individuals. 30 of them have not been involved in voluntary organizations, 30 individuals have joined voluntary organizations and are volunteering at the moment.

The results of the research enable to understand how the living under the Soviet regime has shaped the understanding about volunteering, how the concept of volunteering has been understood in the society, how the attitude towards volunteering has been changing and how it has been related with the development of voluntary sector.

Concept of volunteering

Sociologists and political scientists view volunteering as an expression of core societal principals such as solidarity, social cohesion, and democracy (Putnam 2000; Wuthnow 1998). Volunteering is a complex phenomenon the explanation of which transcends the limits of one single approach because different disciplines such as anthropology, psychology, sociology and economics offer insights into the motives for volunteering (Fiorillo, 2011).

Volunteering, according to Musick and Wilson (2009) is simply work done outside the home and outside job market in an organization setting, performed during the time left over from housework, childcare, and paid work. This description of the phenomenon is in a very simple setting, and clearly draws the line between what volunteering is and isn’t. From a sociological point of view, changes in volunteering could be framed in a broader process of “human development” (Inglehart and Welzel 2005).

Volunteering has been named as a complex phenomenon and has been discussed through the view of the organization, sector, as an activity for the benefit of the society. The concept of volunteering is discussed in a wide range of disciplines as economics, management, and sociology mainly. There is no unique theory, which would unite different meanings and understanding of volunteering.

Volunteer motivation

The phenomenon of volunteering wouldn’t exist in a democratic society without a motivation to be involved in this activity. Thus, although there is agreement that people can benefit from their volunteer work, they must not volunteer for the purpose of gaining those benefits (Musick and Wilson, 2009). The individual participates in an activity for its inherent interest or enjoyment (Finkelstien, 2009). According to Tonurist and Surva (2017), the motives for volunteering can range from broadly altruistic to those being related to the need to fulfil a very specific goal. People may volunteer for reasons that sound purely “selfish” withoutdiminishing in any way the level of commitment they show to the organization they volunteer for (Dekker and Halman, 2003). One historical way of understanding volunteer motivations has been based on theories of altruism and selflessness (Phillips, 1982; Rehberg, 2005), in the sense that the primary motivation is that volunteers want to help others (Bang and Ross, 2009). It might be said that the impact to volunteers, and the impact of motives may be unclear. Volunteer behaviors that appear similar on the surface may reflect different motives for different individuals (Dwyer et al., 2013). Motivations are also always simultaneous rationalizations: they impart volunteers to work with a purpose, confirm a desired identity, and reinforce commitment (Willson, 2000). General motives are also very different from tangible reasons for participating. If volunteering would be described as “good work,” Martin (1994) and Wuthnow (1995) provide a list of motives and feelings like generosity, love, gratitude, loyalty, courage, compassion, and a desire for justice for performing this act. Cnaan and Goldberg-Glen (1991) state that volunteering comes from a single, undifferentiated helping motive. They highlight the word ‘help’ and put it as the single motivational factor to get involved in voluntary activities. Others propound a two-dimensional structure: egoistic motives (defined as satisfactions with tangible rewards) and altruistic motives (defined as satisfactions with the intangible reward of feeling that one has helped someone else (Frisch & Gerrard, 1981) (Harrison, 1995). Most theories of volunteering offer one of two central explanations for people’s decision to volunteer: The first one explains participation in volunteer activity because of moral and social values; the second one conceives of participation in volunteer activity as a result of rational choice (Wilson, 2000) (Brudney and Lee, 2009). They provide evidence that people make the decision to volunteer knowing that the product of their efforts will be shared by the community while they are the sole bearers of the costs.

One of the most influential approaches to the study of motives for volunteering is the functional theory (Clary et al., 1998). According to this theory, any activity that is initiated and maintained over time must be considered useful in the attainment of a personal and meaningful goal (Moisset de Espane´s, 2015). The functional theory proposes that individuals hold certain attitude or engage behaviors because those attitudes and actions meet specific psychological needs, and that different individuals can hold the same attitudes or participate in the same behaviors for very difference reasons (Clary and Snyder, 1991; Katz, 1960; Smith, Bruner, and White, 1956). A central tenet of this approach is that people may volunteer in pursuit of different goals (Dwyer et al., 2013). Functional theory encompasses many of the elements contained within other major theories of volunteer motivation (Phillips and Phillips, 2010). The functionalist approach has suggested that volunteer outcomes are influenced by the extent to which the experience of volunteering satisfies, or “matches,” a person’s underlying motives (Clary et al. 1998). Different volunteers pursue different goals, and the same volunteer may be pursuing more than one goal (Clary and Snyder, 1998). It gives a proof, stated by the authors, that the nature of volunteering is multimotivational. In the specific case of volunteering, the functional approach states that there could be various motives for volunteering, that people could have different motives for engaging in the same volunteer activity, and that the same person could be engaged in volunteering for more than one reason (Moisset de Espane´s, 2015). Furthermore, some models are based on economic theories and emphasize the role of incentives, whereas models developed by sociologists tend to focus on contextual factors as well as psychological motives (Musick & Wilson, 2008).

Proteau and Wolff (2008) have presented motivation to volunteer in three models.

• The reason for individuals to get motivated to participate in voluntary activities is to ‘enhance and enrich their human capital and thus make the greatest employment opportunities or increase their income.’ Volunteering can be seen as a behavioral strategy towards skills or social capital acquisition that can lead to, for example, better employment outcomes (Konstam et al., 2015). Career as a major motivator is highlighted in this model.

• The second model claims that the reason for individuals to volunteer is that they want to improve or to contribute to other peoples’ well-being. The focus of this model is the feeling of empathy

• The third model suggests that volunteering activities are performed due to egoistic reasons as prestige, image in the society, which would benefit in monetary manner through different sources.

Homans (1961) has stated that “Exchange theory is based on the premise that human behavior or social interaction is an exchange of activity, tangible and intangible.” The exchange happens in a form of benefits, giving others something, which is more valuable than it brings cost to the one who is giving. It relates to goals, wishes, needs and expectations discussed in the model.

The basic assumption in the social exchange theory is that people are helping and giving their time to others because they are expecting the return. The return can be in a form of recognition, satisfaction, rewards. The social exchange theory states that the social behavior of exchange brings economic and social outcomes. It includes the connection with another individual and is based on trust rather than legal obligations. Social exchange theory suggests that people contribute to the degree that they perceive that they are being rewarded. (Sergent, Sedlacek, 1990). The social exchange theory states that behavior is governed by the reciprocal relations, for which if the are imbalanced and the individual experiences fewer rewards than costs, the relationship would not be sustained (Zafirovski, 2005).

Volunteering provides people with opportunities to express or demonstrate their beliefs; learn new things; fend off feelings such as guilt, shame, and isolation; and enhance their self-confidence and sense of efficacy.

Cnaan and Amrofel (1994) state, that the social exchange in volunteering happens because of benefits, which are intrinsic and extrinsic. They have divided these benefits info five categories. The first category is tangible or material rewards, which means that helping the other is associated with the benefits that an individual can gain. Internal rewards or good feeling is linked to emotional satisfaction regarding the activity performed and the influence it has done. Social interaction rewards are associated with the ability to communicate with others, to see what benefit is gained from the social interaction by the individuals itself and the others, the recipients. Norms and social pressure arise from the sense of duty, conscientious decision to provide help to others. Avoidance rewards are linked with the uncertainty which unknown situations bring, and which can be related with avoidance to volunteer. Wilson (2000) states that there are two levels of the social exchange. First of all, the individual receives the help when it’s needed, which means that the recipient of volunteering activity has gained the benefits, and the giver has provided the help, which was required. Second, the individual gets involved into voluntary activities because he believes he will need help in the future, which means that gaining benefits of volunteering today are linked and associated with the future need on the volunteering individual.

Volunteering aligns with this theory as it provides people with opportunities to express or demonstrate their beliefs; learn new things; and enhance their self-confidence and efficacy through an exchange relationship (Sherr, 2008).

As individuals volunteer for various reasons, it is important to understand where these motivations come from, which motives are coming from the external environment, which are coming from the individual. Each motive likely comprises multiple dimensions, and their fulfilment may satisfy both intrinsic and extrinsic needs (Finkelstien, 2009).

Historical background

Lithuania has been a part of the Soviet Union, where volunteering has been associated with compulsory activities, performed through the state rule. The collapse of the regime has opened a possibility to develop the voluntary sector and to increase the awareness about it, to increase participation rates. Unfortunately, the development of the voluntary sector has been facing difficulties and attitudes towards volunteering have been changing slowly. An independent institution of public opinion and market research has completed the research (2010) regarding the low volunteering rates and low speed of development. The results have shown that these were influenced by the lack of volunteering tradition in the country (51%), the lack of information about volunteering possibilities (42%), the fact that the education about volunteering and positive attitude towards unselfishness and altruism is not promoted in schools (38%). The attitudes towards volunteering have influenced the participation rates and involvement in voluntary organizations.

The development of the Third sector in Lithuania

The institutional development of the Third sector in Lithuania has had few important stages during the time from 1953 up to now.

The development has been divided into four stages. 1953–1989, the Soviet period – the time when compulsory volunteering activities have been performed. 1991–2000, Reestablishment of independence – no voluntary organizations, the creation of the state, the focus on reestablishment of an independent country. 2000–2010, Development of the third and voluntary sector – creation and development of the sector, creation of the rules, which describe the sector. 2010 to Current date – voluntary organizations active, working in different areas, spread of organization across different sectors and for different causes.

Table 1.

Institutional development of the Third sector in Lithuania

|

Period of time |

Institutional |

Organizational |

Attraction of volunteers |

Individual involvement |

|

|

1953–1989 (Soviet period) Compulsory volunteering |

Organized by the central government, distributed to regions |

No voluntary or third sector organizations |

Compulsory involvement |

All the main benefits are provided by the state, i.e. place of work, housing. Expecting help/ incentives from others |

|

|

1991–2000 Reestablishment of independence – no voluntary organizations |

The main legislation is created, basic principles of law are set |

Reappearance of few religious voluntary organizations like Caritas |

Volunteers are attracted through word of mouth in most cases |

Involvement is spontaneous, when there is a need for it |

Capitalist principles exist, everyone must look after himself. The focus is on family, close relatives |

|

2000–2010 Development of the third and voluntary sector |

Developing legislation for the third/ voluntary sector |

Voluntary organizations are being established in few different areas, i.e. suicide prevention, crisis centers, social help. Continuity issues, weak strategic goals, focus is towards tactics of the organization |

Organizations are in competition for volunteer resources. More sophisticated communication methods are used for the communication with volunteers. |

Low attachment to voluntary organization due to range of different organizations to be joined. Involvement is encouraged through social media, individual contact with a volunteer is created. |

|

|

2010 to Current date. Voluntary organizations active, working in different areas |

Legislation supporting nonprofit sector |

Growth of voluntary organizations through the initiatives by EU, better understanding of society needs. Strategic goals are important part of the organization |

Organizations are working more actively to attract new volunteers, the attraction is more organized, more attention paid to volunteer motivation. Attention paid to the image of the organization, how it is seen by public |

Involvement is encouraged by the development of personal competencies, active attraction through social media, digital media channels. Easy access to information about voluntary sector and organizations, |

Growing trust in voluntary organizations, trust that they fulfil their mission, willingness to donate time or money to people in need |

Third sector organizations during the period of the Soviet Union (1953–1989)

In Lithuania, after losing its independence, the point of view has dramatically been changed towards voluntary organizations and the way they used to function. The Soviet system itself hasn’t provided opportunities to be active in the nongovernmental sector activities. The involvement in the organizations as trade unions and associations has been under radar, under control. Communism, unlike other authoritarian regimes, was particularly detrimental to associational life (Howard and Howard 2003) as it purposively strived to ban any autonomous social life, and instead strived to supplant it with its own structures (Paturyan and Gevorgyan,2014).

The organization, which was the key public organization, was the Communist party. Its focus was to change the point of view to public and third sector organizations, especially which expressed positive views towards voluntary activities, philanthropy. All organizations, i.e. trade unions, youth organizations were provided with all required sources to function like buildings, places of gathering, to promote their activities. The importance of volunteering in the Soviet Union is also shown by the fact that these activities involved children as well as adults (Juknevicius and Savicka, 2003). The nature of these organizations was artificial as they were not initiated by the society and were under full state control. It was publicly declared that they are nongovernmental, voluntary, they have their own regulations. According to the official statistics of 1984, there were 5 sport organizations, 72 science organizations, 6 organizations, which included writers, journalists and painters, 20 organization of various backgrounds, which were branches of other organizations in the Soviet Union (Klokmanienė, & Klokmanienė, 2014). The main feature of the Soviet regime and public organizations was that individuals were encouraged, and sometime forced to join specific organizations. Therefore, according to Juknevicius and Savicka (2003), volunteering was quite frequently compulsory rather than voluntary.

The largest side effect, which was caused by the state control was the rebellious organizations, which were working against the system. Free self-organization was manifest either as simple mutual assistance in the daily routine or within structures established by the state but left outside its total control or, again, as protest against state actions and the official ideology (Jakobson, & Sanovich, 2010).

The changes in the society, the willingness to initiate the change has empowered Baltic states through singing revolution and peaceful action to regain the independence. The dissatisfaction with lack of freedom, misbelief in the regime, has led to ability to initiate the civil change through collective actions, which enables to make a huge change, and make an impact for the collapse of the Soviet regime. The social initiative has led to political changes. The term civil society in the Baltic States is associated with the revolution period from 1989 (Mačiukaitė-Žvinienė, 2008).

Reestablishment of independence – no voluntary organizations (1991–2000)

After the collapse of the Soviet Union regime, the transitional period has started. According to Mačiukaitė-Žvinienė (2008), the transition period had four components. Through public transformation the regime has changed; transition to market economy was an important element of the new state as during the period of the Soviet Union the economy was working in an opposite way; creation of independent state was in process as the new laws, public sector organizations had to be created; preservation of independence was an important element of the period as the new state had to be created together with all the efforts to keep it independent.

The wave of optimism after gaining the independence of the country has led to an opposite side effect in regard to civic engagement. The government authorities focus on building the new democracy. Part of the voluntary or civil organizations has continued their activities after the collapse of the Soviet Union, even though they didn’t receive much attention and weren’t provided with the resources needed for their existence. Part of the funds, which were needed for organizations to function, were received from international organizations. There was a lack of mutual understanding about the need of the third sector in the country. The links between governmental authorities and voluntary organizations were weak or nearly nonexisting.

The change in the society, after gaining its independence, has faced unexpected challenges. One of them was related to the memory of “everything is taken care of for you,” and lack of initiative when the society matters are discussed. The financial instability has been one of the attributes related with shortage of civil initiative. Voluntary, public organizations had to look for other forms of funding, when the system was not there. The fund raising was not existing during the Soviet Union period to the laws of the regime, and the lack of experience in this field has stopped the development of the third sector partially.

Only in 1995 the first statute related to the third sector has been introduced. This had to be as the basis for all the nonprofit organizations to work. It has led to a small boost in creating nonprofit and voluntary organizations. The number of the third sector and voluntary organizations has had the largest rise in the period of 1996–1997. The supportive legislation appeared which has led to increasing number of organizations. Until 2000, the rise of organizations of this type has reached steady growing numbers, according to Ziliukaite (2006). The first survey related to volunteering rates in Lithuania has been done in 1998. It has shown that only 5% of participants have been participating in voluntary activities. Main arguments for not joining voluntary organizations were that the opinion about volunteering and volunteers is not positive. The second reason was that participants were not invited to join voluntary organizations.

Even though the large shift from authoritarian to democratic regime has taken place, the supportive legislation for the third sector organizations has been approved, new opportunities to participate in various voluntary, nonprofit organizations have been created, the interest in activities of this type, in being a member of these organizations was still low. According to Diamond (1999), what has been making a difference in the Baltic countries after the collapse of the Soviet Union, has been the pursuit of ‘Europeanization.’ The willingness to become the member of the European Union has influenced taking over some of the European values.

Development of the third and voluntary sector (2000–2010)

In 2001 the government of Lithuania has made a resolution “The major principles of voluntary work conditions and procedures” (2001, No. 106-3801). The purpose of this document was to provide a clear rule of voluntary organizations, the jurisdictional relationships between volunteers and voluntary organizations. The most important is that this document has provided a definition of a ‘volunteer.’ Since 2007, voluntary activities are part of the Civil Code of the Republic of Lithuania. In 2010, The Ministry of Social Security and Labour of the Republic of Lithuania has prepared “The law of voluntary activities” (2011-07-13, No. 86-4142), which has included definitions, main principals of voluntary organizations and has described control of voluntary organizations.

Since 2004 voluntary organizations had to be included into the Centre of Registers. What is important to mention is that voluntary organizations have been allowed to received funding from profit seeking organizations, individuals. They have received a privilege not to pay any additional taxes.

According to the Centre of Registers, in Lithuania there were 32.476 nonprofit organizations. The Eurobarometer survey completed in 2007 has shown that 11% of citizens have been involved in voluntary activities, compared with 5% in 1998. The data of 2010 shows that 20% of individuals have been involved in voluntary activities (nonregular), and only 4% of individuals were involved in long-term activities.

Even though the legislation to support voluntary organization appears, the system provides bureaucratic obstacles, which do not allow for the voluntary sector to flourish. Baršauskienė, Butkevičienė, & Vaidelytė (2009) have emphasized that most organizations existing in the nonprofit sector are oriented towards social and cultural spheres; their main focus is to provide social services to the groups in need for this type of services together with governmental institutions.

Voluntary organizations active, working in different areas (2010 to Current date)

An independent institution of public opinion and market research company, Vilmorus, has completed the research regarding volunteering in Lithuania. The main reasons for low volunteering and low speed of development are found to be influenced by:

• the lack of volunteering tradition in the country (51%),

• the lack of information about volunteering possibilities (42%),

• the fact that the education about volunteering and positive attitude towards unselfishness and altruism is not promoted in schools (38%).

The survey provided information about the general point of view of the society. The main attitudes towards volunteering are:

• wrong assumptions and understand about the concept of volunteering, i.e. volunteering is associated with charity, with long hours dedicated to specific activity;

• the benefits provided by voluntary action are not fully understood and valued;

• mistrustful and suspicious attitude to voluntary activities, which are performed without pay;

• voluntary activities are not acknowledged as valued working experience.

The results of the research do indicate that even though there is the lack of volunteering tradition in the society, and that the knowledge about volunteering possibilities is not seen, or known, the volunteering organizations are growing and the variety of them increases. The attitudes towards volunteering are known from the research, but there is no data, which would show how the attitudes towards volunteering have been changing with the passage of time, through different periods of time.

Methodology

The purpose of the research is to explore the dynamics of attitudes towards volunteering of individuals who lived under the Soviet regime.

The qualitative research method was chosen as it allows for the description and understanding of main themes and allows to reveal experiences of participants and to discover the changes through their experience. Phenomenography was chosen as a research method as it enables to examine, according to Marton (1986), different ways in which people experience, conceptualize, perceive, and understand various aspects of, phenomena in the world around them. Phenomenography is therefore concerned with describing things as they appear to and are experienced by people (Marton & Pang, 1999). In order to understand the change of attitudes towards volunteering, two groups of participants were required in order to provide a full understanding how the attitudes towards volunteering have been changing, how two groups have seen the same activity and how their attitudes towards it have been seen and changed over the passage of time. The identification of interviewees in phenomenographic studies is typically (and deliberately) nonrandom as this is influenced by the specific phenomenon that is being explored (Åkerlind, 2005; Booth, 1997; Francis, 1996; Marton, 1986). Open-ended questions allow participants to describe personal experiences. Semistructured interviews were conducted with 60 individuals – 17 male, 43 female, who are aged 55–75 years, living in Lithuania. 30 participants are working now; 30 participants are retired (M=64.47 years). The interviews have been conducted June 2021 – December 2021 via telephone and face-to-face. Criteria for participation were for an individual to have the experience of participating in compulsory activities during the Soviet regime. All participants, who are volunteering at the moment have been invited to participate in the research by the employees of the organization. All the participants have been continuing their voluntary activities during the time they have been interviewed. All participants, who are not members of voluntary organizations and are not volunteering at the moment have been invited to participate directly by the researcher, as they do belong for the described age group. Few participants have been invited to participate by other interviewees. The participants were coded according to their volunteering status (volunteer – S, nonvolunteer – NS), gender (woman – M or man – V), and employment status (employed – D, retired – P) and the information about the coded segment.

Religious voluntary organizations have been excluded from the research as the attitude to volunteering may be biased due to religious issues. The interviews were recorded, transcribed, and coded. MAXQDA analysis software was used to analyze the data.

Results

The analysis of the data allowed us to disclose how the period of the Soviet occupation, have influenced the attitude towards volunteering. Participants shared their memories about the experience of living in the Soviet regime and how their opinions towards volunteering have been changing, after the collapsed of the Soviet regime.

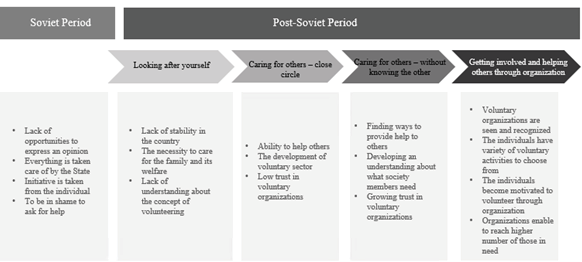

Picture 1.

Change of the attitudes towards volunteering

Picture 1 represents the analysis of the results. The participants have shared their memories about the Soviet period, what were the key aspects of living under this specific regime. The second part of the results enable to reveal the change of attitudes of participants. The focus shifted from “Looking after yourself” to “getting involved and helping others through organizations” with the passage of time.

Soviet period

The data analysis enabled to explore the situation and what was the attitude towards helping others and volunteering during the Soviet period. The society was constrained, which caused the lack of opportunity to express an opinion freely, the initiative was taken from the individual on a personal and societal level. It was imposed that the state provides everything an individual requires, there is no need to ask for help.

• Lack of opportunities to express an opinion

Both groups, volunteers and nonvolunteers, when talking about the Soviet period, recognized that the state tried to create safe society. When they talk about the Soviet period, recognize that the ability to express an opinion freely was limited and fear of expressing an opinion prevailed in society. The freedom to speak loudly about your opinion, personal point of view was an illusion, there was a fear behind. I would say we were frightened. We couldn’t do anything; you couldn’t complain as there were enough people watching behind your back. They were provoking you. (S8VD: 40). The living under regime shapes an individual, where the individual opinion is not valued, where rules of life are stagnant, and where there is lack of freedom, it shapes an individual. The disrespect, which is remembered, is related with the oppression. As it is said, people were living in fear (S8VD: 46). The fear to express an opinion continued even in later times, even when the regime has collapsed. It was related with the unknown rules on what is allowed, and what is forbidden.

• Everything is taken care of by the state

The level of certainty in the society was highly related with the state role in controlling social issues. The regime was built in a way that individual has been taken care of, and no individual initiative was required or even desired: ‘Participants have highlighted that they weren’t giving a lot of thought when they were living under regime. We did not have to think a lot. Everything was taken care of for us. Our job was to complete the tasks. You ‘ve been told, you‘ve completed. You ‘ve been told to go, you go. Today we are on our own. We must think for ourselves (S4MP: 40). The individual’s life has been controlled even though it created an illusion that everything is taken care of, i.e. where to work, where to live, which car to own. We had a relatively calm life, as we had not to think if there will be a job for me after the university. I knew that I would have a career based on my education, the city I will be working in. In a way it was providing a comfort of safety (NS5MD: 20). The state has been built in a way to secure that the system will function properly through planning.

• Initiative is taken away from the individual

Participants associate this period with the idea that initiative was not desired. The sense of stability was calming, and the initiative, the drive, the motivation to change was low. I would say that we were so used to live in the constrain that we even didn’t think about going against the rules or to take individual initiative to change things (NS10VD: 22). Adjusting to the circumstances has meant that the initiative was not needed as it didn’t take you anywhere, neither in your career path nor to a better standard of living. There’s no motivation for anything (S23MD: 36).

• Shame to ask for help

Even though the regime has provided the level of certainty in everyday life, it created an illusion that everything is taken care of for you, the system provided the deficit and shortages. These were the times when the shops were empty, you had to wait for a long time in order to bring something home to eat. We all remember the queues even for small things. (S16MP: 28). It enabled to create inequality and the system where you had to look for a way into the management of the shops, the management of factories. The state has claimed that it provides everything, which is needed for an individual, to satisfy their basic needs are security. The individuals could rely only on the people around them. We did not have much. You had to go and borrow and help to the other (S10MD: 20). It was unacceptable to ask for help from the state. It was shown that the state is providing you with everything you need, despite shortages which we were facing. To ask for some kind of benefits was unimaginable, and unacceptable. And shameful in a way (NS7VD: 14). Only personal help was an option.

After the collapse of the regime, a new era has started. Among participants this period was called ‘survival.’ New challenges for the new democratic state, new doctrine, new circumstances When the Soviet Union has collapsed, and the independence have been regained, there was the time for building a new country, new structure, new society rules. Even though the democratic state has been created, democratic principles were applied, there were plenty challenges for building a civil society. The lack of stability, unstable economic background were the main factors for a weak civil society. As the time has passed, the stability was building up, the society has started to change. The change from “looking after yourself” to “caring about the other members of the society” took more than two decades. The civil society has been building up and at the moment functions through number of organizations, as attitudes towards these kings of organizations and their need to the society is widely recognized.

Post-Soviet period. Looking after yourself

• Lack of stability in the country

After the regime was not existing, the unknown was in every aspect of everyday life. There was a shortage of previous living standards like employment and source of income, the stability of life. “I think we were living in a post-Soviet vacuum. I believe that 1991–2000 was the emptiest time of all. We were trying to survive. Economy was broken, places of work were lost. We were trying to find a way to live. The most difficult time of all. During the Soviet period I had a job, which was well paid, everything was in order. The period of 1991–2000 was the time when you were trying to figure things out how to keep going” (S9VD: 44). The uncertainty has been forcing people to focus on themselves, rather than thinking what is happening around us. People were so tired, overtired and they spent little time thinking about the help to the other, when it’s unpaid especially (NS2MD: 22).

• The necessity to care for the family and its welfare

During the period of the early independence, the focus was on the individual and the close family needs, rather than other members of the society. “There was a time. I’ve been married with a small child. I was looking how to look after my close family. When you’re trying to survive yourself, the egoism and selfishness appear. Until I was calm and sure that I’ve survived that, everything is ok, only then I thought that maybe I could help someone today (S9VD: 46). Therefore, at this post-Soviet period, which was characterized as very instable, people were caring about themselves and their families. The priority was to make sure that your life becomes stable, and your family is taken care of.

• Lack of understanding about the concept of volunteering

Another attribute of the period after was that there was lack of understanding about the concept of volunteering as it was nonexistent during the Soviet regime. “There is no tradition for it. We all have seen how it was difficult for charity to come to our life. Only nowadays charity balls are becoming usual practice. Or even those shot numbers, which allow you to donate. (S5MP: 36). According to participants, most of the society has been understanding volunteering as donations by giving money (I don’t think that I understand the concept of volunteering. I’ve known about volunteering from TV that someone is volunteering, that there is a hotline (NS8MD: 39)), rather than spending time in voluntary organizations, donating their time. The word ‘volunteering’ is new for me. I think that I don’t understand how people are going somewhere after work to do something (NS7VD: 14). Volunteering was associated with worthless activity, when there’s no close connection with the beneficiary. My way of thinking was that I and my family is going first, the survival of them is all that matters. I won’t care for others until I’m fine, when my family is fine (S9VD: 46).

Post-Soviet period. Caring for others – close circle

• Ability to help others

After the first years of regaining the independence have passed, the country started to get more developed, the stability has started to appear. The growing stability in the employment market, in the economy as a whole, have created the attitude: I had everything I need, I’ve given everything my family needs. I was able to give to others (S24VD: 8). Looking after the relatives and the people you know was common. The shortage was so common in so many areas of life, that you had to help each other as you knew that you will get help when its needed. It was binding people together in some weird way ( S10MD: 24). It enabled to see that the quality of life has improved and that there is an ability to live a better life and help others.

• The development in the voluntary sector

Even though the development of the new country was slow and difficult, there was knowledge coming from abroad, and voluntary organizations started to be established in Lithuania. The voluntary sector has started to form. As one creator of voluntary organization remembers: “Even though we didn’t have a clear understanding about volunteering, we wanted to do good for Lithuania. <…> We were trying to visit lonely, retired people. Later on, we added families which are poor, as the independency has started. Many companies went bankrupt, people were unemployed, they lost their source of income, and we were thinking how to help them (S14MP: 6). The tradition of not taking the initiative has started to change slowly. The understanding that there are people in need was there already. It was a difficult time when everything collapsed. Economy has collapsed, the level of unemployment was high, there were people who couldn’t find a way out. It was an empty time, and people were in need (S9VD: 44). And willingness was there: The enthusiasm has been huge. People were coming at 6am, and after providing help went to work. Other volunteers were coming to continue the work, which has been started at 6am (S14MP: 6).

• Low trust in voluntary organizations

Even though the attitude towards volunteering has been changing, there were enough challenges to promote the sector and motivate individuals to join in. The lack of trust in the voluntary sector was vivid and related with the belief that there is lack of transparency and the misuse of funds, as it was done so by “those in power” during the Soviet Union times. There have been so many cases of misuse when someone received benefits for a long time. When people are not getting paid a lot, and they get a part of their salary into their pocket in cash, they will use every occasion. I’m sure there are malignant, who will use every way possible, or holes in the system (NS10VD: 46). In some cases, it is accepted as the heritage of the Soviet period, when it was a common rule to take goods home and not treating it as stealing. We were used to look for a way to live a better life. Stealing is an easier way of earnings. It was “fashionable” to steal. There was a common understanding that it is acceptable to steal. (S24VD: 20). The distrust in the voluntary organizations was related with the previous experiences, and didn’t disappear immediately, it faded with the passage of time. I do believe that there always be people who will behave as they were used to, i.e. will steal on every occasion they have. I do believe there will be people who will look for benefit for themselves first. But there are good people, too, who are sincere, and doing everything for the benefit of others (NS10VD: 49).

Even though there were new possibilities and the variety of organizations was growing, factors like lack of transparency together with the bad publicity and rumors had not created a favorable environment to get involved. There was a scandal regarding money in this organization and when you’re donating, some of your donations are going not into the right pocket. There was an article about it (S21VP: 52). I’ve heard, and I’ve seen how people are going there and are using every occasion to bring something home, like my neighbor. She doesn’t go to the grocery store, as there is enough food she brings after volunteering (NS10VD: 46).

Post-Soviet period. Caring for others without knowing the other

• Finding ways to provide help to others

The understanding that there are people in need was there already, only there were limitation and lack of information of ways how to support them, how to help them, as willingness was there. The most common way to provide help was through donations of food or money, rather than spending time volunteering. I buy something when they are making those one-day events. If it goes to those who really need it, it’s a decent help in my opinion (NS2MD: 24). Even though the spread about voluntary organizations was limited, the possibility to help others in need was existing and more acknowledged by the society.

• Developing an understanding about what society members need

The country has reached the level of stability, and the level of living has increased. The volunteering comes from the fact that I’m calm and I’m provided with all I need, and I am able to give without any risk for my wellbeing (S24VD:26). As the survival mode was switched off for some member of the society, they have noticed that there are people in need and that they have the resources to provide the help. The better we live, the more we want to volunteer (S9VD: 42). Various groups of society have different need varying from food, clothes to the psychological help. Giving to others was associated with the sense of fulfilment, joy, to be needed, to be useful. I had free time and wanted to find an activity. And it is good that I’m being needed and useful (S21VP: 6). It enabled to look how to help others and think about volunteering. I would say that it’s not about me feeling good. Volunteering for me is associated with helping the other. That’s the need I’m fulfilling (S27MP: 63).

• Growing trust in voluntary organizations

The trust in voluntary organizations was very low at the beginning of the regained independence. The lack of trust in voluntary organizations was associated with the benefit for the volunteer himself. I do think that at the beginning people were hoping to benefit themselves, as I will go to the food warehouse, I will get something myself too (NS1MD: 44). As the transparency of organizations grew, the trust has been building up, as the variety of organizations has enabled different groups of society to receive the help. The trust in voluntary organizations was growing with the passage of time. I do believe that you have to try it yourself in order to avoid wrong conclusions. Since I’ve tried and participated, I do know if that was working for the right cause or not. Try it yourself and avoid wrong rumors (S16MP: 34).

The trust in the sector was influenced by the view to volunteering. Participants have highlighted that at the beginning they have experienced lack of support from their family and friends. They have built the trust in voluntary organizations and the benefits it provides to other members of the society. The volunteers in the family have encouraged to be more involved through donations. They have a positive attitude towards my volunteering, as my son and my daughter in law are also willing to help others. They are very positive regarding my activities. My husband is the same, too (S15MP: 20).

Post-Soviet period. Getting involved and helping others through organizations

• Voluntary organizations are seen and recognized

The transparency and good communication has encouraged individuals to join voluntary organizations.

You join voluntary organizations because there’s no obligation to join. You have a variety to choose from, where your skills are the most useful. I’ve joined the organization which I’ve felt is suitable for me as I’m able to gain new experience, to try myself out, to learn new things without the feelingof being exploited (S26MD: 38). Even though there are people, who have strong memories about the Soviet regime, the disadvantages of it, the circumstances they were living in, but their mind-set has changed. I do believe that everyone has to experience the turning point in order to get involved in volunteering or to be the leader of this kind of activity (NS5MD: 34). As the organizations are becoming more public, they are getting more publicity, the individuals recognize the ways how they could be useful for those organizations and how they could fit in. I’m volunteering for an organization where my experience is directly related, i.e. working with people who have an addiction. I’ve been addicted myself in the past, and only people who have experienced it can understand and provide the needed support. (S25MD: 24) The voluntary organizations are attracting members through publicity and communication of how everyone could be beneficial for the society.

• Individuals have variety of voluntary activities to choose from

Volunteering in the past has been seen as the activity where the physical help is needed. As the spread about volunteering organizations expands, individuals find ways how to get involved through phone, through their work, through their place of employment. There is an understanding that if you have achieved a lot and you are successful, it is expected that you would help others in need. When people have high income, have achieved a lot in their career, they do find time and ways how to help others (NS11MD: 43). Individuals value the encouragement from the people they know, and they do find through word of mouth how they could get involved. And majority of participants highlight the “being asked,” as a motivator for them to join or get involved.

• The individuals become motivated to volunteering through organization

The freedom of choice, which is existing in the society, give a lot of choice for action. Volunteer participants associate involvement in volunteering with caring for others, as there is no uncertainty regarding themselves. Changing attitudes towards volunteering from the Soviet regime to the period of reestablishment of independence and to nowadays are showing that there is a place where the society members care for each other not because everyone is in need and doing an exchange, like in the Soviet times. The stability and the knowledge about voluntary organizations, how they function, how transparent they are, what purpose do they serve, encourages motivated individuals to get involved. I do like management; I would find a way how to use my time there in the most useful way. I do like the community when each helps the other (NS9MD: 42). Organizations enable to reach higher number of those in need

As voluntary organizations are widely seen and recognized, and the right amount of publicity is there, individuals can see the impact they make through their voluntary activities. The impact for a larger number of people in need is seen in specific organizations. I do meet various people every time I go to volunteer. We do chat and discuss the difficulties they are facing, or the difficulties they have passed. Even though I’m getting back home tired, I do see that there are more than two people who benefit from what I do (S5MP: 16). Volunteers highlight the importance of the feedback they receive. It motivates to continue what they are doing and enables to see the impact they make. It works like an encouragement to continue what you’re doing, and that your time was spent wisely and for the right purpose (S17MD: 23).

Conclusions

The attraction and retention of volunteers are vital components of the operation of a nonprofit organization (NPO) (Zjoba et al., 2020). When the civil society is not strong, and is in its early development phase, it is important to bring required tools which would help for the civil society to grow. It is important that voluntary organizations would look closer to the individuals, and using their past experiences and attitudes towards volunteering would create opportunities for volunteering. Motivation to volunteer could be encouraged by making volunteers feeling needed. Values and that their skills could be used to fit to the purpose of the organization.

The research explored five different periods, which enables to show the change and understand how it affects the understanding about volunteering, how individuals have changed, how the changing environment has influenced the change of attitudes. The understanding about volunteering has been changing from the Soviet times up to now in different stages, enabling individuals to get more knowledge, to experience the change of the state together with the societal change. Negative memories, memories about oppression have shaped the behavior of individuals, which are directly related with the willingness to volunteer, understanding the benefits of volunteering, attitudes towards it. To better recruit and retain volunteers, we must have a thorough understanding of their motivations (Zjoba et al., 2020).

Picture 2.

Change of the attitudes towards volunteering in Lithuania

The attitudes towards volunteering have been changing as the development of the third sector was evolving in the country. The institutional development is an important component when the attitudes towards volunteering are discussed. When compared with Western countries, the volunteering tradition has started to grow only when a certain level of economic development has been reached.

The main traits of each period (Picture 2) show what the main stages for building a civil society might be when a specific regime collapses. The individual perspective at the beginning of the period is widening and through caring for yourself, family members, other members of the society to an organizational level, where the individuals act through organization rather than an individual approach. It enables to expand the reach of those in need, and the benefits provided to the society are widely recognized. The Northern European countries and Great Britain had the highest rates of volunteer activity in Europe (Hodgkison, 2003). In “Eastern block” countries formerly under communist rule, such as Bulgaria, East Germany, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania and Russia, an undeveloped civil society leaves little room for independent volunteer work (Musick and Wilson, 2000). It is highlighted by researchers that the length of experience under totalitarian regimes decreases generalized trust, which is one of the factors influencing the numbers of volunteers in the specific country. The research has enabled to highlight the change from totalitarian regime and how it affects the attitude towards volunteering.

According to Butkuviene (2005), the development impact for the attitude towards volunteering is associated with economic state of individuals, ego attitude and the heritage of the Soviet experience. With the passage of time, the attitude towards volunteering has changed and individuals join voluntary organizations because of transparency, which is related to the trust in the sector and organizations. Individuals become more aware of the organizations, but they have to prove and show that they pass the test of honesty, transparency.

The future research could be focused on how voluntary organizations could attract individuals. To better recruit and retain volunteers, we must have a thorough understanding of their motivations (Zjoba et al., 2020). What techniques could work when working with this specific age group of individuals, who could be valuable members of the organizations and of the society.

References

Anheier, H. K., & Salamon, L. M. (1999). Volunteering in Cross-National Perspective: Initial Comparisons. Law and Contemporary Problems, 62(4), 43. https://doi.org/10.2307/1192266

Bang, H., & Ross, S. D. (2009). Volunteer motivation and satisfaction. Journal of Venue and Event Management, 1(1), 61–77.

Baršauskienė, V., Butkevičienė, E., & Vaidelytė, E. (2008). Non-governmental organizations and their activities. Technology.Technologija, 10.5755/e01.9786090210246

Black, B., & Jirovic, R. L. (1999). Age differences in volunteer participation. Journal of Volunteer Administration, 17, 38–47.

Butkuvienė, E. (2005). Dalyvavimas savanoriškoje veikloje: situacija ir perspektyvos Lietuvoje po 1990-ųjų. [Voluntary Participation: Situation And Perspectives In Lithuania After 1990’s]. Sociologija. Mintis Ir Veiksmas [Sociology. Thought and Action], 16, 86–99. https://doi.org/10.15388/socmintvei.2005.2.5999

Clary, E. G., & Snyder, M. (1991). A functional analysis of altruism and prosocial behavior: The case of volunteerism. In M. S. Clark (Ed.), Prosocial behavior (pp. 119–148). Sage Publications, Inc.

Clary, E. G., & Snyder, M. (1999). The motivations to volunteer: Theoretical and practical considerations. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 8, 156–159.

Clary, E. G., Snyder, M., Ridge, R. D., Copeland, J., Stukas, A. A., Haugen, J., & Miene, P. (1998). Understanding and assessing the motivations of volunteers: a functional approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(6), 1516–1530. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.74.6.1516

Cnaan, R. A., & Amrofell, L. (1994). Mapping volunteer activity. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 23(4), 335–351. https://doi.org/10.1177/089976409402300404

Cnaan, R. A., & Goldberg-Glen, R. S. (1991). Measuring motivation to volunteer in human services. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 27(3), 269–284. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886391273003

Dekker, P., & Halman, L. (2003). The values of volunteering: Cross-cultural perspectives. Springer Science & Business Media.

Diamond, L. (1999). Developing democracy: Toward consolidation. JHU Press.

Dwyer, P. C., Bono, J. E., Snyder, M., Nov, O., & Berson, Y. (2013). Sources of volunteer motivation: Transformational leadership and personal motives influence volunteer outcomes: Sources of volunteer motivation. Nonprofit Management & Leadership, 24(2), 181–205. https://doi.org/10.1002/nml.21084

Ellis, S. J., & Noyes, K. H. (1990). By the people. A History of Americans as Volunteers.

Finkelstien, M. A. (2009). Intrinsic vs. extrinsic motivational orientations and the volunteer process. Personality and Individual Differences, 46(5–6), 653–658. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2009.01.010

Frisch, M. B., & Gerrard, M. (1981). Natural helping systems: A survey of Red Cross volunteers. American Journal of Community Psychology, 9(5), 567–579. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00896477

Harrison, D. A. (1995). Volunteer motivation and attendance decisions: Competitive theory testing in multiple samples from a homeless shelter. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 80(3), 371–385. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.80.3.371

Hendricks, J., & Cutler, S. J. (2004). Volunteerism and socioemotional selectivity in later life. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 59(5), S251-7. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/59.5.s251

Hodgkinson, V. A. (2003). Volunteering in Global Perspective. In Nonprofit and Civil Society Studies (pp. 35–53). Springer US.

Homans, G. C. (1961). Social behavior in elementary forms. A primer of social psychological theories. Brooks/Cole Publishing Company.

Howard, M. M., & Howard, M. M. (2003). The weakness of civil society in post-communist Europe. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511840012

Jakobson, L., & Sanovich, S. (2010). The changing models of the Russian third sector: Import substitution phase. Journal of Civil Society, 6(3), 279–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/17448689.2010.528951

Juknevičius, S., & Savicka, A. (2003). From restitution to innovation: Volunteering in postcommunist countries. In Nonprofit and Civil Society Studies (pp. 127–142). Springer US.

Katz, D. (1960). The functional approach to the study of attitudes. Public Opinion Quarterly, 24(2, Special: Attitude Change), 163. https://doi.org/10.1086/266945

Klokmanienė, D., & Klokmanienė, L. (2014). Social activities of non-governmental organizations. Study book. Panevėžys: Panevėžys College

Konstam, V., Celen-Demirtas, S., Tomek, S., & Sweeney, K. (2015). Career adaptability and subjective well-being in unemployed emerging adults: A promising and cautionary tale. Journal of Career Development, 42(6), 463–477.

Lee, Y.-J., & Brudney, J. L. (2009). Rational volunteering: a benefit‐cost approach. The International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 29(9/10), 512–530. https://doi.org/10.1108/01443330910986298

Mačiukaitė-Žvinienė. (2008). Non-Governmental Organizations in the Baltic States: Impact on Democracy. Doctoral dissertation. Mykolo Romerio Universitetas.

Martin, M. W. (1994). Virtuous giving: Philanthropy, voluntary service, and caring. Indiana University Press.

Moisset de Espanés, E. (2015). Investigación cualitativa en la enseñanza de asignaturas proyectuales.

Musick, M. A., & Wilson, J. (2008). Volunteers: A social profile. Indiana University Press, Bloomington.

Marton, F. (1986). Phenomenography - A research approach to investigating different understandings of reality. Journal of Thought, 21(3), 28–49.

Marton, F., & Pang, M. F. (2008). The idea of phenomenography and the pedagogy of conceptual change. In S. Vosniadou (Ed.), International Handbook on Research of Conceptual Change (pp. 533–559). Routledge.

Okun, M. A., & Schultz, A. (2003). Age and motives for volunteering: testing hypotheses derived from socioemotional selectivity theory. Psychology and Aging, 18(2), 231–239. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.18.2.231

Parboteeah, K. P., Cullen, J. B., & Lim, L. (2004). Formal volunteering: a cross-national test. Journal of World Business, 39(4), 431–441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2004.08.007

Paturyan, Y., & Gevorgyan, V. (2014). Trust towards NGOs and volunteering in South Caucasus: civil society moving away from post-communism? Journal of Southeast European and Black Sea Studies, 14(2), 239–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/14683857.2014.904544

Penner, L. A., & Finkelstein, M. A. (1998). Dispositional and structural determinants of volunteerism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(2), 525–537. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.2.525

Phillips, L. C., & Phillips, M. H. (2010). Volunteer motivation and reward preference: an empirical study of volunteerism in a large, not-for profit organization. SAM Advanced Management Journal, 75(4).

Phillips, M. (1982). Motivation and expectation in successful volunteerism. Journal of Voluntary Action Research, 11(2–3), 118–125. https://doi.org/10.1177/089976408201100213

Plagnol, A. C., & Huppert, F. A. (2010). Happy to help? Exploring the factors associated with variations in rates of volunteering across Europe. Social Indicators Research, 97(2), 157–176. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-009-9494-x

Prouteau, L., & Wolff, F.-C. (2008). On the relational motive for volunteer work. Journal Of Economic Psychology, 29(3), 314–335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2007.08.001

Rehberg, W. (2005). Altruistic individualists: Motivations for international volunteering among young adults in Switzerland. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 16, 109-122. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-005-5693-5

Sergent, M. T., & Sedlacek, W. E. (1990). Volunteer motivations across student organizations: A test of person-environment fit theory. Journal of College Student Development, 31(3), 255–261.

Silló. (2016). The Development of Volunteering in Post-Communist Societies. A Review. Acta Universitatis Sapientiae-Social Analysis, 6(1), 93-110.

Smith, M. B., Bruner, J. S., & White, R. W. (1956). Opinions and personality. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Tõnurist, P., & Surva, L. (2017). Is volunteering always voluntary? Between compulsion and coercion in co-production. VOLUNTAS International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 28(1), 223–247. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-016-9734-z

Wilson, J. (2000). Volunteering. Annual review of sociology, 26, 215-240. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.215

Wuthnow, R. (1995). Learning to care: Elementary kindness in an age of indifference. Oxford University Press.

Yates, C., Partridge, H., & Bruce, C. (2012). Exploring information experiences through phenomenography. Library and Information Research, 36(112), 96–119. https://doi.org/10.29173/lirg496

York, A. S. (2009). Social work with volunteers, by M. e. sherr: Chicago: Lyceum books (2008). Journal of Community Practice, 17(3), 350–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705420903121223

Zafirovski, M. (2005). Social exchange theory under scrutiny: A positive critique of its economic-behaviorist formulations. Electronic Journal of Sociology, 2(2), 1–40.

Zboja, J. J., Jackson, R. W., & Grimes-Rose, M. (2020). An expectancy theory perspective of volunteerism: the roles of powerlessness, attitude toward charitable organizations, and attitude toward helping others. International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing, 17, 493–507. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12208-020-00260-5

Žiliukaitė, R. (2006). Trust: from theoretical introspection to empirical analysis. Culturology, 13, 205-252.