Social Welfare: Interdisciplinary Approach eISSN 2424-3876

2024, vol. 14, pp. 54–69 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/SW.2024.14.4

Addressing the Housing Crisis: Insights from a Study on University Students in Turkey

Doğa Başar Sarıipek

Kocaeli University

Zahide Peker

Kocaeli University

Gökçe Cerev

Kocaeli University

Abstract. Housing stands as a fundamental human right, acknowledged by numerous international bodies and statutes. Despite this recognition, only a handful of nations ensure adequate housing for their populace. This research endeavors to forge a connection between housing rights and social policy through a comprehensive literature review. Drawing from data provided by the Turkish Statistical Institute and the Ministry of Youth and Sports, the study addresses the escalating housing concerns among university students in Turkey. With an increasing student population and insufficient accommodation facilities, the issue has reached a critical juncture. Most students are compelled to reside in state dormitories, which lack the capacity to meet demand. Moreover, economic hardships and a dearth of financial aid exacerbate the housing crisis. The findings underscore the urgent need for the development of policies and solutions tailored to address the housing predicament faced by university students in Turkey.

Keywords: Right to housing, social policy, university students, welfare

Received: 2024-02-15. Accepted: 2024-03-12

Copyright © 2024 Doğa Başar Sarıipek, Zahide Peker, Gökçe Cerev. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access journal distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

Throughout history, the right to housing has remained a cornerstone of social policy, closely intertwined with the social welfare and well-being of individuals. Access to suitable housing is pivotal in fostering a secure and nurturing environment for individuals and their families. Particularly crucial for marginalized communities, housing stands as one of the fundamental requisites influencing their overall welfare. In Turkey, university students, facing various disadvantages, grapple with numerous housing challenges that demand attention and resolution.

A primary housing challenge confronting university students in Turkey revolves around the scarcity of affordable and appropriate accommodation. Numerous students grapple with the unavailability of reasonably priced housing near their campuses, compelling them to endure lengthy commutes or settle for inadequate living conditions. Such circumstances not only impede their academic focus but also jeopardize their overall welfare. Moreover, the insufficiency of student housing compounds the issue. While governmental bodies and certain universities offer dormitory options, the limited capacity often fails to meet demand, leaving many students without access to affordable and secure housing, heightening their vulnerability. Additionally, concerns persist regarding the quality of existing student accommodations, with many lacking essential amenities and failing to foster an environment conducive to academic and social growth. These deficiencies can detrimentally affect students‘ well-being and impede their full engagement in university life.

Solving the housing challenges faced by university students in Turkey necessitates a holistic strategy encompassing governmental action and university cooperation. The government must allocate resources towards constructing affordable student housing complexes while also enforcing quality standards for existing facilities. Simultaneously, both governmental entities and universities should prioritize furnishing appropriate accommodation choices for students and cultivate an environment conducive to their support and success.

In summary, housing rights are pivotal within social policy, and resolving the housing issues faced by university students in Turkey is imperative for their holistic well-being and welfare. Through facilitating access to affordable and appropriate housing options, both governmental bodies and universities play a pivotal role in fostering an environment conducive to students‘ academic and social flourishing.

The aim of this study is to explore the relationship between housing rights and welfare through a comprehensive literature review. Utilizing descriptive analysis methodology, this research examines primary data sources including the Turkish Statistical Institute, the Ministry of Youth and Sports of Turkey, and the OECD. Despite existing research on housing rights, particularly concerning university students as a distinct demographic within social welfare, there remains a scarcity of literature in this area. This study aims to fill this gap by specifically evaluating the housing rights of Turkey‘s substantial youth population, with a focus on university students, both within the context of social policy and in comparison to OECD countries. Furthermore, the study seeks to provide valuable insights by identifying areas of concern and proposing potential solutions within this critical domain.

Upholding Human Dignity: Exploring the Right to Housing in International and Turkish Legal Frameworks

Undoubtedly, housing stands among the most fundamental rights afforded to individuals. This encompasses the entitlement of every person to reside in conditions that are safe, healthy, and dignified. Such a right encompasses access to housing of high quality across physical, economic, and social dimensions. The primary objective of housing rights is to guarantee individuals the opportunity to dwell in environments that are secure and conducive to good health. Aligned with this objective, measures are implemented to prevent homelessness and to facilitate the availability of affordable housing, supplemented by state aid to address housing challenges (Steward, 1989; UN Habitat, 2009).

The core essence of housing rights is intimately intertwined with „the right to human dignity“ (Kucs, Sedlova, & Pierhurovica, 2008). Numerous countries incorporate provisions regarding housing or the right to housing within their national constitutions, reflecting an approach that underscores the obligation of states to ensure adequate housing for their populace (Madden & Marcuse, 2016). Moreover, the right to housing serves as a benchmark in international human rights standards and is enshrined within the framework of social rights, notably articulated in Article 25 of the 1948 UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights. This article stipulates:

“Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services, and the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond his control.” (UN, 1949).

Article 11(1) of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) declares:

“The States Parties to the present Covenant recognize the right of everyone to an adequate standard of living for himself and his family, including adequate food, clothing and housing, and to the continuous improvement of living conditions. The States Parties will take appropriate steps to ensure the realization of this right, recognizing to this effect the essential importance of international co-operation based on free consent.” (UN, 1966).

The right to housing is additionally affirmed in Article 17 of the 1976 UN International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. A significant milestone concerning housing rights at the global level is the Vancouver Declaration on Human Settlements, endorsed at the UN Conference on Human Settlements (HABITAT I) in 1976. Further advancements include the adoption of the ‚Habitat Agenda‘ and the ‚Istanbul Declaration‘ during the Habitat II Conference in 1996, serving as foundational documents for UN-HABITAT. Subsequently, the „New Urban Agenda“ established at the III HABITAT Conference represents another stride towards international housing rights and policies (Kucs, Sedlova, & Pierhurovica, 2008).

The lack of affordable housing compels individuals living in poverty to grapple with the challenge of prioritizing essential human necessities (Gomez & Thiele, 2005). The link between homelessness, substandard living conditions, and human dignity is pivotal from a legal perspective, as the right to human dignity has evolved into a universally acknowledged customary law. This signifies its legal obligation upon all nations, irrespective of their adherence to human rights treaties, safeguarding the right to housing (Kucs et al., 2008).

The notion of human dignity, a fundamental constitutional principle, finds expression in the preamble of the Constitution of the Republic of Turkey as:

“…every Turkish citizen has an innate right and power, to lead an honourable life and to improve his/her material and spiritual wellbeing under the aegis of national culture, civilization, and the rule of law, through the exercise of the fundamental rights and freedoms set forth in this Constitution, in conformity with the requirements of equality and social justice…” (TBMM, 1982).

Additionally, the Constitution of the Republic of Turkey includes several articles concerning fundamental rights and freedoms (Articles 10, 12, 13, 14, 15, 17, and 19), which encompass provisions for the safeguarding of human dignity (TBMM, 1982; Elif, 2019).

Harmonizing Housing Rights and Social Welfare: A Global Perspective

The progression of human rights and the concept of the social welfare state, both cantered on human well-being, have evolved in tandem. The legal framework of human rights emerged post-World War II and gained legitimacy alongside the expansion of the welfare state across continental Europe. In this regard, the social welfare state endeavors to enhance the welfare and standard of living of its citizens through the implementation of social policies (Manoochehri, 2010). Social policy augments traditional policies by incorporating social dimensions that impact both individual and societal well-being. Integral to the concept of social policy are welfare provisions, designed to aid individuals and families in need by granting access to essential services and resources. Encompassing facets such as healthcare, education, housing, and social security, social policy plays a pivotal role in shaping resource allocation and service delivery to promote the welfare and prosperity of the populace (Blakemore & Griggs, 2013; Spicker, 2013). The right to housing, essential for human dignity and social justice (Bengtsson, 2001), is regarded as a cornerstone of welfare state policies within the realm of social policy. Over time, in alignment with the principles of the welfare state, the recognition of housing as a „right“ has prompted states to develop policies in this domain.

The right to housing encompasses the assurance of individuals‘ access to a secure, hygienic, and habitable dwelling. From a welfare standpoint, social policy endeavors to guarantee equitable access to adequate housing for all (Pandey, 2011; Schmid, 2020). However, the extent of this right varies across nations and is contingent upon the particular social welfare framework in place (Bengtsson, 2001; Manoochehri, 2010).

Bengtsson (2001) distinguishes between two primary types of state housing policies: selective and universal. In a selective housing policy, housing rights entail legally mandated minimum standards for households with lower incomes. Conversely, within the context of a universal housing policy, the right to housing is recognized as a „social right,“ aligning with the government‘s obligation to the entire society. Turkey is among the nations that have committed to providing fair and equitable welfare services to its citizens, adopting a welfare regime approach rooted in the principle of citizenship and embracing its duty (Öçal et al., 2022).

The right to housing is closely intertwined with housing affordability, which hinges on individuals‘ disposable income and encompasses both the provision of housing services and associated expenses (Bieri, 2012). Government interventions in the housing market differentiate housing policies in Western societies. Within this context, housing distribution primarily operates through market contracts, with state intervention influencing the economic and institutional framework governing these contracts (Bengtsson, 2001). Moreover, the development of affordable housing options through public–private partnerships and community initiatives is pivotal in enhancing housing accessibility for marginalized groups. By collaborating with developers and community organizations, welfare-oriented housing policies can foster the creation of diverse housing options tailored to the specific needs of different populations (Owczarzak et al., 2013; Donaldson & Yentel, 2019). State interventions in housing markets to promote housing opportunities encompass financing housing producers to boost housing production, providing housing subsidies, income support, or implementing tax regulations for housing consumers (households) (Taşar & Çevik, 2009). Social policy bears the responsibility of formulating and implementing housing rights policies, establishing mechanisms to offer affordable housing options for low-income households and those with specific housing needs (Mkandawire, 2004).

When examining global approaches to housing within welfare frameworks, it becomes evident that different countries have adopted diverse strategies concerning housing rights from a welfare perspective. In certain nations, the welfare system places a strong emphasis on establishing a robust social safety net with comprehensive housing benefits and support for those in need. For instance, Scandinavian countries like Denmark and Sweden view housing as a fundamental right, with the welfare system offering generous housing allowances, subsidies for affordable housing, and social housing programs to ensure all citizens have access to adequate and secure housing (Kemendy, 2001; Ritakallio, 2003). Conversely, in countries like the United States and the United Kingdom, housing policies oriented towards welfare often concentrate on providing housing assistance through means-tested programs, public housing initiatives, and rental subsidy schemes. Nevertheless, the availability and quality of affordable housing options vary significantly, posing obstacles to guaranteeing equitable housing opportunities for marginalized groups (Bengtsson, 2001; Kemendy, 2001). Furthermore, in developing nations, housing policies prioritizing social welfare may center on initiatives such as slum renovation, affordable housing schemes, and formalizing informal settlements to enhance living standards for marginalized communities. These endeavors typically involve collaborations among governmental agencies, nonprofit organizations, and international aid programs to address housing disparities and promote housing security for disadvantaged individuals (Wakely, 2015).

The right to housing and living in a healthy environment, which stands as a fundamental focus of social policy practices, not only constitutes a basic human right but also fosters social inclusion and justice within society. Particularly crucial for individuals in low-income groups or disadvantaged positions, housing opportunities carry immense significance (UN HABITAT, 2009). The absence of access to adequate housing opportunities exacerbates poverty for individuals (Doling et al., 2017) and presents a notable risk in terms of social justice and public health (Voituriez & Chancel, 2021). The burgeoning issue at hand has evolved into a substantial crisis within the contemporary global landscape. Termed as the housing crisis, it encompasses a dearth of housing facilities, presenting formidable challenges for individuals and families seeking accessible, affordable, and adequate housing options. Concurrently, this crisis is characterized by soaring housing prices, restricted housing access, and exacerbating housing disparities (Poggio & Whitehead, 2017). While the origins of this crisis are multifaceted and intricate, key factors such as the erosion of the welfare state, the ascendancy of neoliberal policies, and heightened market interference in housing have played pivotal roles. Specifically, the neoliberal paradigm, propelled by global financial markets, has precipitated reductions in welfare state provisions, conspicuous spikes in homelessness rates, and reductions in social housing-related services and resources (Poggio & Whitehead, 2017; Perrotta, 2020).

A crucial aspect of welfare-oriented housing policies involves integrating supportive services alongside housing assistance. By providing access to healthcare, mental health services, and educational resources, these policies aid individuals in addressing the underlying challenges contributing to housing insecurity and instability (Spicker, 2013). In conclusion, the welfare perspective on housing rights underscores the importance of ensuring equitable access to safe and adequate housing for all members of society. By addressing the distinctive challenges encountered by marginalized populations and furnishing essential support and resources, welfare programs play a significant role in realizing housing rights and advancing the broader objectives of social policy.

Bridging the Gap: Housing, Education, and Socio-Economic Dynamics in Turkey

Although the history of university education spans many centuries, modern educational organizations emerged prominently after World War II, coinciding with a significant increase in student enrolment (Neubeck & Neubeck, 1999). Various factors influence the trajectory of university students‘ educational experiences, with the socio-economic background of their families being a key determinant. There exists a direct relationship between a family‘s socio-economic status, its support for the student throughout their educational journey, and the student‘s level of educational attainment and living conditions (Blanden & Gregg, 2004; Crosnoe et al., 2002; Şengönül, 2013). Children from lower socio-economic backgrounds often face more challenging living conditions, whereas those from higher socio-economic groups tend to enjoy higher living standards (Blakemore et al., 2006; Bradshaw et al., 2011). As Bozkurt (2015) pointed out, education can have a dual impact on social inequalities: while access to education can propel individuals toward higher social classes, those lacking access or experiencing limited opportunities tend to have lower living standards. Viewed through the lens of social policy, education possesses dual significance: it not only holds promise in diminishing societal inequalities but also acts as a conduit for fostering social cohesion. Hence, the calibre of social welfare provision emerges as a pivotal factor influencing students‘ engagement in education.

The rise in university enrolments and the ongoing global housing affordability crisis are closely intertwined on a worldwide scale (Marginson, 2016; Sotomayora et al., 2022). In Europe, the housing circumstances of young individuals have been influenced by the resurgence of commodification, financialization, and the state‘s retreat from its role as a housing provider (Riedl, 2020). The surge in ‚studentification‘ within urban areas hosting universities has highlighted the state‘s failure to furnish adequate accommodation and living conditions for students, prompting the private sector to assume a dominant role (Calvo, 2018; French et al., 2018).

Many university students grapple with housing insecurity, which encompasses issues of affordability, safety, and accessibility (Suzanna et al., 2021). The lack of affordable accommodations imposes significant stress on their academic endeavours, health, and overall well-being (Suzanna et al., 2021; Martinez et al., 2021; Sotomayora et al., 2022). With the cost of living on the rise, there has been a notable increase in the number of university students unable to pursue their education due to housing affordability constraints (Du Plessis & Amoah, 2022). This underscores the impact of housing affordability on students‘ ability to exercise their right to education.

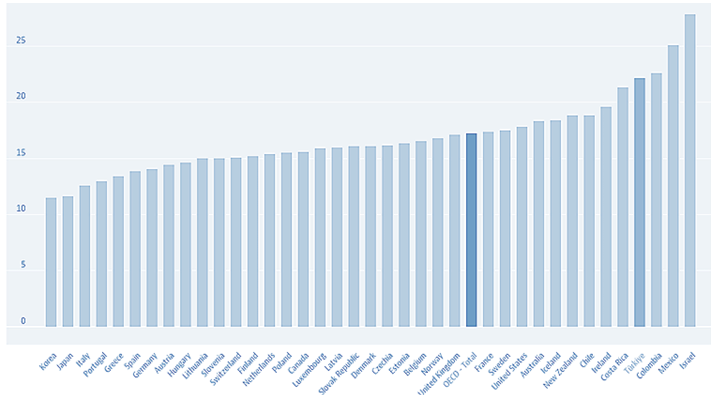

Turkey is among the nations that must prioritize addressing housing issues affecting its youth population. According to data from the Turkish Statistical Institute, 15.2 percent (12,949,817 people) of the country‘s total population (85,279,553 people) falls within the age range of 15–24. Moreover, it‘s reported that 49.3 percent of this young population is of age between 18 and 22, coinciding with the period of bachelor education (TUİK, 2023). When comparing the proportion of youth populations with other countries, Turkey notably stands out, boasting one of the highest percentages of youth among OECD nations, at 22.2 percent (compared to the OECD average of 17.3 percent), as depicted in Graphic 1 (OECD, 2024). This unequivocally underscores the significance of young people for the country.

Graphic 1.

Total per cent of young population among OECD countries, 2022.

Resource: https://data.oecd.org/pop/young-population.htm

In the academic year 2021/22, there were a total of 208 higher education institutions, comprising 129 public universities, 75 foundation universities, and 4 private vocational schools. According to data from the Council of Higher Education, during this period, 8,296,959 students were enrolled in higher education institutions, with 4,454,128 students in open education programs and 3,842,831 in formal education programs across 204 institutions. Within formal education, 3,162,232 students attended public universities, while 671,437 students were enrolled in foundation universities. Additionally, there were 9,162 students studying at private and foundation vocational colleges (YÖK, 2023). According to Ministry of National Education data published in 2023, a total of 812,313 graduates were enrolled in tertiary education during the 2021/22 academic year (MEB, 2023).

Table 1 illustrates the distribution of education expenditure at the tertiary level. While the table underlines a noticeable increase in education spending, Turkey ranks among the countries with the lowest education expenditure among OECD nations, specifically ranking third from the bottom. To elaborate, Turkey‘s total expenditure on tertiary education amounts to 9,288 USD, compared to the OECD average of 18,105 USD. However, Turkey has surpassed the OECD average (4.9 percent) by allocating 5.2 percent of its GDP to education expenditures (OECD, 2023a; OECD, 2023b).

Table 1.

Tertiary level education expenditure by financial source in Turkey, 2022

|

(Million TRY) |

Year |

Total |

Public expenditures |

Government |

||

|

Total |

Central |

Local |

||||

|

Tertiary education |

2011 |

22 731 |

20 424 |

20 370 |

53 |

2 895 |

|

2012 |

27 619 |

24 230 |

24 163 |

67 |

3 484 |

|

|

2013 |

30 656 |

27 017 |

26 919 |

98 |

3 923 |

|

|

2014 |

35 258 |

31 127 |

31 073 |

55 |

4 677 |

|

|

2015 |

40 338 |

35 642 |

35 590 |

52 |

5 633 |

|

|

2016 |

47 766 |

43 803 |

43 744 |

59 |

8 258 |

|

|

2017 |

54 501 |

48 770 |

48 698 |

71 |

8 944 |

|

|

2018 |

69 914 |

60 200 |

60 125 |

76 |

10 116 |

|

|

2019 |

74 491 |

59 750 |

59 698 |

52 |

9 849 |

|

|

2020 |

87 663 |

70 636 |

70 575 |

61 |

10 195 |

|

|

2021 |

115 573 |

93 142 |

93 042 |

99 |

12 673 |

|

|

2022 |

201 235 |

158 365 |

158 154 |

211 |

19 054 |

|

Resource: Turkish Institute of Statistics

Housing is widely acknowledged as a crucial determinant of individuals’ well-being. Moreover, university students‘ housing conditions significantly impact their physical, mental, and emotional health (Franzoi et al., 2022). Various factors influence the housing situation of European university students. For instance, French (2018) underscores the demand for affordably priced, high-quality student housing in major European cities, presenting investment opportunities. Oppewal et al. (2005) demonstrate that UK university students prioritize physical amenities and proximity to campus when selecting accommodation. Similarly, Thomsen and Eikemo‘s (2010) research reveals that Norwegian university students prioritize certain physical conditions in their accommodation, such as spacious rooms, personal space, private bathrooms, reliable internet, and convenient location, and are willing to pay higher fees for improved conditions. In Antwerp, Belgium, a study found that students‘ housing preferences primarily revolve around the type of accommodation, with studio apartments preferred over shared dormitories. This strong preference for private facilities indicates that shared housing is not the top choice among Antwerp students. While rent is a significant factor for students, similar to their Norwegian counterparts, they are willing to incur extra expenses to have access to their own kitchen and bathroom facilities (Verhetsel et al., 2017). Gong and Söderberg (2023) argue that government subsidies for student housing in Sweden are insufficient considering factors such as the number of students, physical amenities (e.g., kitchen facilities, cleanliness, proximity to public transportation, and room size), and fees, all of which significantly impact housing satisfaction. Muslim (2012) discusses the challenges faced by off-campus students, emphasizing the importance of a satisfactory living environment.

The housing arrangements of Turkish university students typically fall into three main categories, aligning with global trends: residing with parents or close family members, living in student houses, or staying in dormitories. Various studies have delved into the housing conditions of university students in Turkey. According to Filiz and Çemrek (2007), students predominantly opt for state dormitories due to economic convenience and proximity to school. Similarly, Poyraz (2000) found economic factors to be the primary determinant for choosing state dormitories. In both studies, the physical conditions of accommodation, such as having personal space, cleanliness, conducive study environments, and dining facilities, are key considerations influencing the preferences of students staying in private dormitories and student houses. Özgür et al. (2010) identified „inadequate physical environment“ as the most significant drawback of dormitory living, whereas students residing in student houses perceived the physical environment of their accommodations as more suitable. Additionally, the study found that dormitory living enhanced students‘ social skills and facilitated their physical needs. Kuşderci and Güllü‘s (2011) research, involving 2972 university students, identified affordability as the primary reason for choosing state dormitories, particularly among students from low-income families. Despite economic constraints, students and families perceived dormitory living as reassuring, as highlighted in the same study. Gürler et al. (2012) reached similar conclusions, demonstrating that economic considerations primarily drove students‘ preference for state dormitories. Uğur‘s (2020) study, which compared living conditions of university students over a decade, revealed that housing and transportation expenses absorbed most of students‘ financial resources, leaving little room for socio-cultural activities due to financial constraints. Collectively, these studies underscore the pivotal role of universities in ensuring students‘ right to adequate housing.

The quantity of tertiary student dormitories in Turkey is on the rise, aligning with the growing student population, as depicted in Graphic 2. Most of these dormitories are state-owned, reflecting the government‘s commitment to social policies. Nevertheless, despite the increasing number of dormitories, their capacity remains insufficient compared to the student population, and the quality of conditions provided is often questionable.

Graphic 2.

Number of students enrolled in higher education and state dormitory capacities 2021/2022

Resource: MEB. (2023). Milli Eğitim İstatistikleri, Örgün Öğrenim, Milli Eğitim Bakanlığı.

Field studies conducted in Turkey have unveiled that the primary challenge faced by university students stems from economic constraints. A significant portion of students endeavor to complete their studies through state-provided loans or scholarships, while those lacking these opportunities often resort to part-time employment (Kete Tepe & Özer, 2020). Research indicates that all student groups, aside from those engaged in employment, rely on financial assistance from their families or other sources. Moreover, national data reveals that the leading cause of dropouts among young people in Turkey, encompassing university students, is financial difficulties. Approximately 51.1% of students discontinued their education due to factors such as the high cost of education, financial obligations to their households, or transitioning into the workforce (TURKSTAT, 2022). Comparing the number of Turkish university students with the number residing in state dormitories, it‘s evident that Turkish students exhibit a lesser inclination towards alternatives beyond state-provided housing, unlike their European counterparts. Therefore, the literature review suggests that the inadequacy of financial resources among Turkish university students represents the most significant obstacle for them to experience university life comparable to their global peers. Given that housing constitutes one of the primary expenditures, addressing this issue becomes paramount for students. Consequently, students grappling with economic inadequacies face challenges in fully exercising their right to education.

Future Perspectives: Enhancing the Right to Housing for University Students

The surge in global demand for higher education has elevated student housing as a pressing issue. University students encounter challenges in securing suitable accommodation, necessitating solutions to uphold their housing rights. This discourse delves into the socio-economic repercussions of inadequate housing, the responsibilities of educational institutions, and policy suggestions to cultivate a supportive housing milieu for students. The literature underscores the pivotal role of housing policies and practices in safeguarding the housing rights of university students.

The European Students‘ Union (ESU) highlights several noteworthy national initiatives in Europe aimed at improving the student housing situation. In Finland, students benefit from subsidized housing and receive monthly housing allowances. Additionally, the Netherlands has established housing associations that excel in providing suitable and high-quality housing, fostering a culture of collaboration among the government, student unions, universities, and housing associations. In Germany, student unions actively advocate for the expansion and enhancement of current student housing options, advocating for accessibility and affordability for all students (ESU, 2019). Italy, grappling with a shortage in fulfilling the demand for student housing, has earmarked €960 million for the development of new student accommodation facilities, including the repurposing of abandoned structures, as part of the National Plan for Recovery and Resilience (PNRR) (Calcagnini et al., 2023).

The increasing enrollment rates in Turkish universities have heightened the demand for accessible and affordable student housing. Beyond being essential for academic success, adequate housing plays a central role in fostering students‘ overall well-being and development.

The repercussions of inadequate and below-par student housing are profound, affecting academic performance, mental health, and the overall student experience. Taking cues from successful housing models in different areas, the suggested recommendations are geared towards assisting policymakers, educational institutions, and pertinent stakeholders in formulating effective strategies to bolster the housing rights of university students.

The demand for universities to offer housing choices that align with student expectations is increasing (La Roche et al., 2010). Advocating for a housing strategy grounded in rights and imbued with an intergenerational justice perspective is suggested as a viable means to address the housing crisis among youth and reinstate social welfare (Riedl, 2020). Addressing economic challenges among students necessitates macro-level solutions, including the implementation of scholarship programs and financial aid initiatives tailored to disadvantaged students (El Ansari & Stock, 2010). Consequently, efforts persist to guarantee students‘ access to appropriate and affordable housing, fostering an environment conducive to their academic and personal growth.

Conclusion

The global visibility of the housing crisis is increasingly apparent, with notable effects observed in Europe, particularly impacting the well-being of the younger generation. Despite housing being recognized as one of the fundamental human needs and its right guaranteed by international conventions, research findings reveal that housing problems among university students are prevalent globally. The research indicates that university students commonly encounter housing issues, exacerbated by the growing college student population and limited housing options. The majority of students are found to reside in state dormitories, which often lack the capacity to adequately accommodate their needs. Additionally, students‘ housing challenges are compounded by economic hardships and insufficient financial support. The need for social welfare provisions is most acute among young people, particularly university students who have yet to fully enter the workforce. This underscores the state‘s responsibility in ensuring welfare and can be seen as an indication of the failure of neoliberal policies, which have contributed to the onset of the housing crisis. Welfare measures, recognized for their positive impact on individuals‘ living conditions, social integration, and overall well-being, must therefore play a central role in addressing the housing issue.

Existing research collectively emphasizes the urgency for effective policy interventions targeting younger generations to tackle the housing crisis within the framework of social welfare. The findings of this study underscore the imperative to formulate policies and solutions aimed at alleviating the housing challenges encountered by university students in Turkey. This suggests that the data derived from the descriptive analysis align with prior studies in the literature. An initial step involves evaluating current accommodation policies and bolstering the capacity of existing dormitories. This entails enhancing accessibility to state-funded housing projects and diversifying alternative accommodation options. However, any capacity expansion must be conducted within appropriate parameters to meet students‘ needs effectively. Additionally, it‘s crucial to ensure that these initiatives align with students‘ economic circumstances and preferences. Furthermore, enhancing the provision of financial assistance, such as loans and scholarships, is imperative. The Turkish government should increase its contribution to the share of higher education expenditure allocated to student welfare to facilitate these efforts. By implementing these recommendations, significant progress can be made in alleviating the housing issues faced by university students in Turkey, ultimately improving their living conditions.

References

Bengtsson, B. (2001). Housing as a Social Right: Implications for Welfare State Theory. Scandinavian Political Studies, 24, 255-275. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9477.00056

Bieri, D. S. (2012). Housing affordability. Michalos, Alex C. (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Quality of Life Research. New York/Heidelberg: Springer Verlag.

Blakemore, K., & Griggs, E. (2013). Social Policy: An Introduction. Third Edition. Mcgraw-Hill Education, Open University Press.

Blakemore, T., Gibbings, J., & Strazdins, L. (2006). Measuring the socio-economic position of families in HILDA and LSAC. In ACSPRI Social Science Methodology Conference, University of Sydney, December 10-13. https://conference2006.acspri.org.au/proceedings/streams/SEP%20paper.%2013_11_06.pdf

Blanden, J., & Gregg, P. (2004). Family income and educational attainment: a review of approaches and evidence for Britain. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 20(2), 245-263. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/grh014

Bozkurt, V., (2015). Değişen Dünyada Sosyoloji [Sociology in a Changing World]. Ekin Basım Yayın Dağıtım.

Bradshaw, J., Keung, A., Rees, G., & Goswami, H. (2011). Children‘s subjective well-being: International comparative perspectives. Children and Youth Services Review, 33(4), 548-556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.05.010

Calcagnini, L., Magarò, A., & Trulli, L. (2023). University Student Housing as a Synergistic Tool between University and City. In: Gervasi, O., et al. (Eds.), Computational Science and Its Applications – ICCSA 2023 Workshops. ICCSA 2023. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 14104. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-37105-9_43

Calvo, D.M. (2018). Understanding international students beyond studentification: A new class of transnational urban consumers. The example of Erasmus students in Lisbon (Portugal). Urban Studies, 55, 2142-2158. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098017708089

Çelik, E. (2019). İnsan Hakları Hukukunda İnsan Onurunun Yeri ve Rolü [The Place and Role of Human Dignity in Human Rights Law], Hacettepe Hukuk Fakültesi Dergisi [Hacettepe Law Review], 9(2), 282-310. https://doi.org/10.32957/hacettepehdf.635313

Crosnoe, R., Mistry, R. S., & Elder Jr, G. H. (2002). Economic disadvantage, family dynamics, and adolescent enrollment in higher education. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64(3), 690-702. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00690.x

Doling, J., Vandenberg, P., & Tolentino, J. (2013). Housing and Housing Finance - A Review of the Links to Economic Development and Poverty Reduction. Asian Development Bank Economics Working Paper Series, 362. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2309099

Donaldson, L P., & Yentel, D. (2019). Affordable Housing and Housing Policy Responses to Homelessness. In: Larkin, H., Aykanian, A., Streeter, C.L. (Eds.), Homelessness Prevention and Intervention in Social Work (pp. 103-122). Springer eBooks, 103-122. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-03727-7_5

Du Plessis, J., & Amoah, C. (2022). Affordable Student Accommodation: A Perspective of Tertiary Students. Proceedings of International Structural Engineering and Construction, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.14455/ISEC.2022.9(1).HOS-02

El Ansari, W., & Stock, C. (2010). Is the Health and Wellbeing of University Students Associated with their Academic Performance? Cross Sectional Findings from the United Kingdom. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 7(2), 509-527. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph7020509

ESU. (2019). Students’ Housing in Europe: The students’ perspective on the overall situation, main challenges and national best practices. https://www.esu-online.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/2019_ESU_Student_Housing_Info-Sheet-1.pdf

Filiz, Z., & Çemrek, F. (2007). Üniversite Öğrencilerinin Barinma Sorunlarının Uygunluk Analizi ile İncelenmesi [An Examination of the Accommodation Problem of University Students through Multiple Correspondence Analysis]. Eskişehir Osmangazi Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi [Journal of Social Sciences, Eskişehir Osmangazi University], 8(2), 207-224. https://doi.org/10.5961/jhes.2019.345

French, N., Bhat, G.M., Matharu, G., Guimarães, F.O., & Solomon, D. (2018). Investment opportunities for student housing in Europe. Journal of Property Investment & Finance, 36(6), 578-584. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPIF-08-2018-0058

Gomez, M., & Thiele, B. (2005). Housing Rights Are Human Rights. Human Rights Journal, 32, 3, 2-5.

Gong, A., & Söderberg, B. (2023). Residential satisfaction in student housing: an empirical study in Stockholm, Sweden. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-023-10089-z

Güllü, K., & Kuşderci, S. (2011). Yükseköğrenim Kredi Ve Yurtlar Kurumunun Verdiği Hizmetlerin Üniversite Öğrencileri Tarafından Algılanması: Sivas Yurtkur Örneği [University Student’s Perception of Services Provided by Higher Education Credit and Dormitories Institution (HECDI): Sivas HECDI Example]. Erciyes Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi [Erciyes University Journal of Social Sciences Institute], 1(30), 185-209. https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/pub/erusosbilder/issue/23764/253304

Kemeny, J. (2001). Comparative housing and welfare: Theorising the relationship. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 16, 53–70. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1011526416064

Kete Tepe, N., & Özer, Y. (2020). Üniversite Öğrencilerinin Yoksulluk Algısı Üzerine Nitel Bir Araştırma [A Qualitative Research on the Poverty Perception of University Students]. Uluslararası Yönetim Akademisi Dergisi [International Journal of Management Academy], 3(1), 166-188. https://doi.org/10.33712/mana.700429

Kılıç, M. (2020). Konut Hakkının Sosyopolitiği: Sosyal Haklar Sistematiği Açısından Bir Çözümleme [Socio-Politics of the Right to Housing: An Analysis in Terms of Social Rights Systematic]. Anayasa Yargısı [Constitutional Jurisdiction], 37(2), 67-112. https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/pub/anayasayargisi/issue/59080/850259

Kucs, A., Sedlova, Z., & Pierhurovica, L. (2008). The right to housing: International, European, and National perspectives. Cuadernos Constitucionales de la Cátedra Fadrique Furió Ceriol, 64, 101-123.

La Roche, C. R., Flanigan, M. A., & Copeland Jr, P. K. (2010). Student housing: Trends, preferences and needs. Contemporary Issues in Education Research (CIER), 3(10), 45-50. https://doi.org/10.19030/cier.v3i10.238

Manoochehri, J. (2010). Social Policy and Housing: Reflections of Social Values [PhD Thesis, UCL (University College London)]. https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/19217

Marginson, S. (2016). The worldwide trend to high participation higher education: Dynamics of social stratification in inclusive systems. Higher Education, 72(4), 413–434. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-016-0016-x

Martinez, S. M., Esaryk, E. E., Moffat, L., & Ritchie, L. (2021). Redefining basic needs for higher education: It’s more than minimal food and housing according to California university students. American Journal of Health Promotion, 35(6), 818-834. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890117121992295

MEB. (2023). Milli Eğitim İstatistikleri, Örgün Öğrenim, Milli Eğitim Bakanlığı [National Education Statistics, Formal Education, Ministry of National Education]. https://sgb.meb.gov.tr/meb_iys_dosyalar/2023_09/29151106_meb_istatistikleri_orgun_egitim_2022_2023.pdf

Mkandawire, T. (2004). Social policy in a development context: Introduction. In Social policy in a development context (pp. 1-33). London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230523975_1

OECD (2023). “Türkiye”, in Education at a Glance 2023: OECD Indicators. OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/fe3f366e-en

OECD (2023b). Taking stock of education reforms for access and quality in Türkiye. OECD Education Policy Perspectives, 68. OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/5ea7657e-en.

OECD (2024). Young population (indicator). https://doi.org/10.1787/3d774f19-en

Owczarzak, J., Dickson‐Gómez, J., Convey, M., & Weeks, M. R. (2013). What is „Support“ in Supportive Housing: Client and Service Providers‘ Perspectives. Human Organization, 72(3), 254-262.

Özgür, G., Babacan Gümüş, A., & Durdu, B. (2010). Evde ve Yurtta Kalan Üniversite Öğrencilerinde Yaşam Doyumu [Life Satisfaction of University Students Living at Home or in the Dormitory]. Psikiyatri Hemşireliği Dergisi [Journal of Psychiatric Nurses], 1(1), 25-32. https://jag.journalagent.com/z4/vi.asp?pdir=phd&plng=tur&un=PHD-44153

Pandey, P. (2011). Right to Adequate Housing in India: Human Rights Perspective. Social Science Research Network. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1922129

Perrotta, C. (2020). The Welfare State and Its Crisis. In: Is Capitalism Still Progressive?. Palgrave Pivot, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-48169-8_5

Poggio, T., & Whitehead, C. (2017). Social Housing in Europe: Legacies, New Trends and the Crisis. Critical Housing Analysis, 4(1), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.13060/23362839.2017.3.1.319

Riedl, V. (2020). Right to housing for young people: On the housing situation of young Europeans and the potential of a rights-based housing strategy. Intergenerational Justice Review, 6(1), 4-13. https://doi.org/10.24357/igjr.6.1.794

Schmid, C., U. (2020). The Right to Housing as a Right to Adequate Housing Options. European Property Law Journal, 9(2-3), 157-178. https://doi.org/10.1515/eplj-2020-0006

Şengönül, T. (2013). Sosyal Sınıfın Boyutları Olarak Gelirin, Eğitimin ve Mesleğin Ailelerdeki Sosyalleştirme-Eğitim Süreçlerine Etkisi [The influence of income, education and occupation as dimensions of one’s social class on families’ socialization-education processes]. Eğitim ve Bilim [Education and Science], 38(167). http://egitimvebilim.ted.org.tr/index.php/EB/article/view/1477

Sotomayor, L., Tarhan, D., Vieta, M., McCartney, S., & Mas, A. (2022). When students are house-poor: Urban universities, student marginality, and the hidden curriculum of student housing. Cities, 124, 103572. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2022.103572

Spicker, P. (2013). Principles of Social Welfare: An Introduction to Thinking about the Welfare State. London: Routledge. http://hdl.handle.net/10059/891

Stewart, F. (1989). Basic Needs Strategies, Human Rights, and the Right to Development, Human Rights Quarterly, 11(3), 347–374. https://doi.org/10.2307/762098

Taşar, M. O., & Çevik, S. (2009). Sosyal Konut ve Konut Sektörüne Devlet Müdahalesi: Avrupa Ülkeleri ve Türkiye [Social Housing and State Intervention in the Housing Sector: European Countries and Turkey]. Aksaray Üniversitesi İktisadi ve İdari Bilimler Fakültesi Dergisi [Journal of Aksaray University Faculty of Economics and Administrative Sciences], 1(2), 133-163. http://aksarayiibd.aksaray.edu.tr/tr/pub/issue/22557/241019#article_cite

Thomsen, J., & Eikemo, T. A. (2010). Aspects of student housing satisfaction: A quantitative study. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 25(3), 273–293. https://doi.org/10. 1007/ s10901- 010- 9188-3

TÜİK. (2022). Türkiye Aile Yapısı Araştırması, 2021 [Family Structure Survey in Turkey, 2021]. Türkiye İstatistik Kurumu. https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Bulten/Index?p=Turkiye-Aile-Yapisi-Arastirmasi-2021-45813

TÜİK. (2023). İstatistiklerle Gençlik, 2022 [Youth in Statistics, 2022]. Türkiye İstatistik Kurumu. 2022. https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Bulten/Index?p=Istatistiklerle-Genclik-2022-49670

UN Habitat. (2009). The Right to Adequate Housing UN Fact Sheet, 21/Rev.1. Geneva: UN. https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Publications/FS21_rev_1_Housing_en.pdf

UN. (1949). Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 3381. United Nations, General Assembly Department of State, United States of America. https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights

UN. (1966). International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. United Nations. https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/international-covenant-economic-social-and-cultural-rights

Verhetsel, A., Kessels, R., Zijlstra, T., & Bavel, M.V. (2017). Housing preferences among students: collective housing versus individual accommodations? A stated preference study in Antwerp (Belgium). Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 32, 449-470. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10901-016-9522-5

Voituriez, T., & Chancel, L. (2021). Developing countries in times of COVID: comparing inequality impacts and policy responses. World Inequality Lab. France. https://policycommons.net/artifacts/3775265/developing-countries-in-times-of-covid/4580961/

Wakely, P. (2015). Reflections on urban public housing paradigms, policies, programmes and projects in developing countries. International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development, 8(1), 10-24. https://doi.org/10.1080/19463138.2015.1055077

YÖK. (2023). Üniversite İzleme ve Değerlendirme Genel Raporu 2023, Üniversite İzleme ve Değerlendirme Komisyonu [University Monitoring and Evaluation General Report 2023, University Monitoring and Evaluation Commission]. Yüksek Öğretim Kurulu, Ankara. https://www.yok.gov.tr/Documents/Yayinlar/Yayinlarimiz/2023/2023-universite-izleme-ve-degerlendirme-genel-raporu.pdf